“Follow 2013: Existence,” group exhibition with Chen Tianzhuo, Gao Mingyan, Liao Fei, Su Chang, Xiao Longhua, Zhang Yunyao, Andy Mo (Zhu Zi).

MoCA Shanghai (People’s Park, 231 Nanjing Xi Lu, Shanghai). Feb 23 – Apr 21, 2013.

Wang Weiwei’s latest curatorial effort with “Follow 2013: Existence” turns up some interesting new talents showing off irreverent attitudes and intriguing explorations of form.

Wang, the curator at Shanghai’s MoCA, has in the past distinguished herself with her intimate knowledge of the practices of China’s young artists but also has the good taste to present their most interesting works. Her young artists exhibition series “Follow” which began in 2011 at MoCA has been very much worth following; her restraint in the number of artists — dictated by the space, of course — resulted in a show at a variance from sprawling exhibitions about “young artists” up north in Beijing (CAFAM, UCCA).

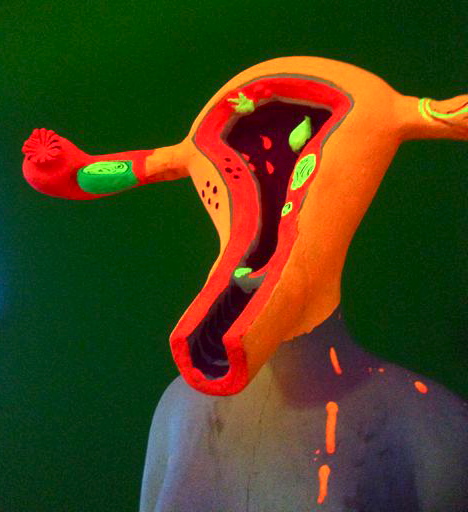

Despite the lack of a strong thematic thread, the show nonetheless displayed some interesting individual oeuvres of China’s up-and-coming artists. Definitely the most eye-catching work was Chen Tianzhuo’s ode to mind-altering substances — a roundish shamanic-like hut in the center of the space, with black walls adorned with a variety of objects: masks, clothing, crude sculptures of monkeys standing on their hands balancing piles of organs on their feet, a giant rug, educational posters on how to smoke pot, a psychedelic fractal-like video and row of phallic-shaped hand-blown glass bongs — the “yang” counterpart to the “yin” — sculptures of women with their heads replaced by ovaries. The contents of Chen’s freaky head shop are lit up by a blacklight which illuminates day-glow oranges, yellows and greens applied to the surface of the sculptures in a primitive fashion. Chen’s work in general stands out for stylistic impudence. The work takes the devil-may-care and somewhat juvenile attitude of Double Fly and moves it in a more formalistic territory. But whereas Double Fly distills this “Jackass” brand of humor into an oily essence to be consumed for pure pleasure, Chen’s punk/pot aesthetic is aiming to make a comment on spirituality. This strange primitive lair / voodoo shrine is a kind of stage in which to act out the rituals of “a new modern religion” — one based on mind expansion and sexual exploration.

On the surface, the work doesn’t really explore any intensely deep territory, but once the topic of religion is highlighted via the wall text, the work becomes more interesting. Chen’s religion, though it has the props and trappings of other mainstream religions, seems to have few moral principles — which makes it look something more akin to cult — indeed it’s a fine line.

The other body of work which really stood out in this show was that of Gao Mingyan — a continuation of a train of thought he has been developing for a number of years with his “Room 404” series where used books as his medium — turning them into sculptural objects. This new group of paintings and installations involves the alterations of everyday objects, fans, high-healed shoes and chairs. Perhaps most inspiring is the milk-crate/sedan chair, book/parachute and fan/windmill. These works fall into a category of (for lack of a better word) “whimsical artwork” — the kind of work which aims to entertain, to coax a little smile out the corner of the mouth of the viewer — something along the lines of “Ceci n’est pas un pipe.”

Yet as with Magritte, there is more than a punch line. There is also the beauty in finding creativity and imagination in the dreariness of the everyday. One can just imagine the artist in the environs of the used goods market full of beat-up old appliances and things, blaring pop music, people shouting and smoking and grasping these unwanted, unloved objects and transforming them into objects of wonder.

(Sidenote: For more on Gao Mingyan, see “Exercises of Living,” now on at Vanguard Gallery, which features a nice series of equally whimsical paintings on the theme of transforming objects and animals into useful machines.)

Andy Mo also incorporates found objects into his work in “They Crossed, They Too, But He Didn’t,” which consisted of a sheet of glass studded with circles of rabbit fur, stone, metal and sponge. The effect is such that it looks like the rocks and pieces of metal gears are plunging through the glass with fissures of fur splintering out around them. At the same time the fur creates the odd effect of motion, as if these random objects are spiraling off into the cosmos.

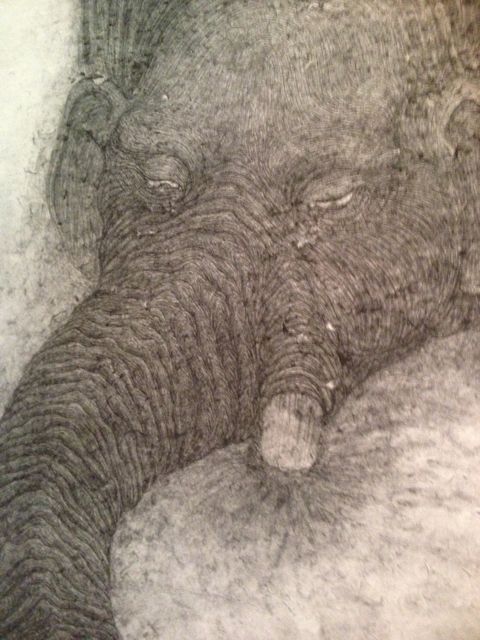

This motion effect is replicated in his drawing work, dense charcoal creations — line after line after line all arranged in a parallel formations — the cumulative effect of which creates the sleeping body of an elephant, a languid whale or a dense crop of mushrooms which seem to grow taller and taller by the minute. His subjects seem to have a way of being both dead and alive — contemporary and primordial at the same time — as if they straddle some kind of temporal chasm.

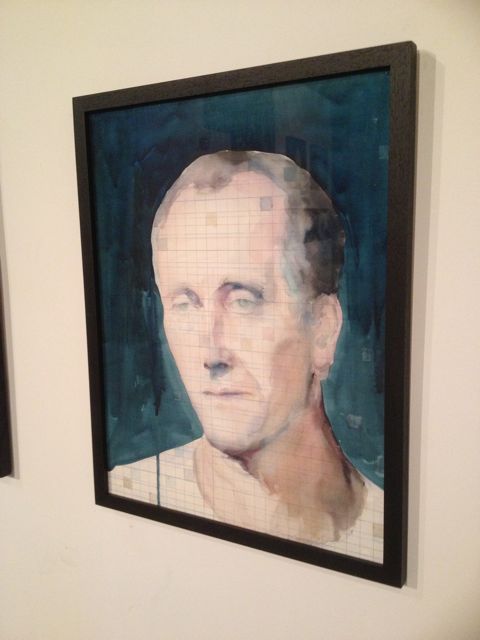

Also producing some striking drawings was Zhang Yunyao, with his “Black” series. Though the subject matter was somewhat mundane, the technique of charcoal on felt created a fantastic velvety texture which was quite entrancing on a formalistic level.

In general it’s safe to say that the overall strength of the show was on a level of form. No doubt they posses a great curiosity in terms of exploring the bounds of their mediums, but what the show lacked was a sharp and focused examination of ideas and issues. Form should have served as a vehicle for some sort of coherent message or idea but all to often it was just an end in itself.