by Alice Gee

Thao Nguyen Phan ‘Becoming Alluvium’

Chisenhale Gallery (64 Chisenhale Rd, Bow, London E3 5QZ) Sept. 26, 2020 – Dec. 6, 2020

Thao Nguyen Phan’s Becoming Alluvium, comprising a single-channel video and a series of lacquer and silk paintings, arrives at the Chisenhale Gallery in London after exhibitions in Brussels and Barcelona. In these European cities, Phan scoops up the voyeuristic gaze of the European tourist, sweeps it into the all-mighty Mekong, and washes it downstream in a mythic and lyric journey. Along the way, Phan interrogates French colonial travelogues and re-imagines them by passing a corrective lens over distortions of Vietnamese culture, past, and present.

Six stacked blocks confront us as we enter the dark, cavernous room. Delicate white strands trickle from the top left corner and collect in a in the bottom right corner. They look like the relics of lightening or the fossilized sinews of some great beast. ‘It’s an aerial view of the Mekong river’ Ellen Grieg, the curator tells me, ‘The white lines are eggshell. The slabs aren’t the compressed sediment of the river, either, but Lacquer, or ‘Son Mai , a traditional and laborious art form. This work, titled ‘Perpetual Brightness’, was made in collaboration with Truong Cong Tung — a Vietnamese artist who majored in Lacquer Painting. Shiny and severe, they demand the entrant’s meditative attention. In the vastness of our planet’s time and space, am I too, a tiny fragment of eggshell trickling into some collective pool?

‘Power and fragility’ is the dichotomy Phan interrogates. The whirring of a boat’s engine booms from grey paneled speakers. Three-legged silver stools constellate the space before the screen. These stools were designed by Architect Anh Cuong Nguyen of NhaBe Scholae to mimic the flimsy, plastic stools Vietnamese shop-owners perch upon. These stools, with their shiny spindling legs, would look better placed on the moon than the streets of Ho Chi Minh.

The ‘First Reincarnation’ begins. In one section, the camera’s gaze lingers over the limp bodies of two brothers, lain across felled logs on a riverbank. They blow whistles. The sound is labored, as if they have whistled for eternity. In this scene, Phan lavishes the touristic gaze with a feast of luscious greens and dappling water. Then, for a moment, a shot of a tomb, encased in glass in a stale red room, breaks the fecundity and expanse of the Mekong.

In this fictional myth, these boys are victims of a dam collapse who reconcile in the next life as an Irrawaddy dolphin and a water hyacinth. In real life, two years ago in Laos, a hydropower dam collapsed. 40 people died, 1000 disappeared, and the tragedy displaced 6,600 others. Hydropower dams ravage the ecosystem of the Mekong, the river’s integrity already undermined by sewage and plastic. The piercing whistles of these young ghosts, which overheard might be mistaken for the cries of birds, is Becoming Alluvium’s most emphatic alert to the Mekong ecological crisis.

This dam collapse, besides other ecological and current affairs in South East Asia, failed to pique the interest of western, European media. ‘Who does, and doesn’t, get to be a part of the ecological revolution?’ Ellen asks. Despite a growing expression of concern and anxiety about the environment, northern-hemisphere eco-activists are mostly detached from the real-life, current effects of climate change upon the south-western hemisphere. The only exception to this rule is the widespread horror at the Australian bushfires, a nation more familiar to Europe.

So how does western media frame the south-eastern hemisphere? Through which frames of references do European viewers situate and contextualize Becoming Alluvium? In Britain, South-east Asia is packaged through the panoramic lens of big-budget travel documentaries, or the cropped and filtered Instagram squares of gap-year back-packers. Phan’s film may employ majestic, sweeping shots, and concern real and serious environmental and economic issues, but Becoming Alluvium is not a documentary.

As the cultural critic and artist Trinh T. Minh Ha asserted ‘there is no such thing as documentary’: any ‘objective’ documentation of real life just asserts the subjective gaze of the filmmaker. Taking up her baton, Phan resists and revises reductive documentations of Vietnam, and evades any closed didactic solution to the ecological and cultural issues she poses.

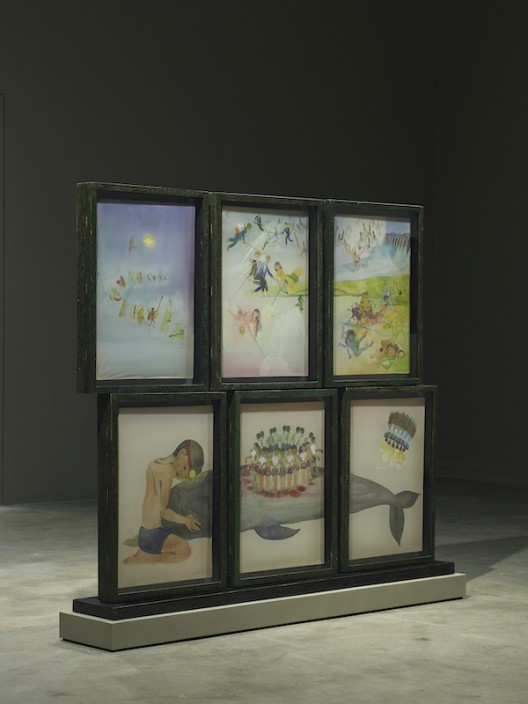

It is in the film’s ‘Last Reincarnation’ chapter that Phan most powerfully achieves what Toni Morrison might term a ‘re-memory’ of Vietnamese colonial past. Phan retells a Khmer folktale: the story of a princess who demands a man produce jewelry as beautiful as dew. Painted animations accompany the tale, which Phan intersperses with a slideshow of photographic stills and engravings — records from French explorer Louis Delaporte’s voyage to find the source of the Mekong.

Thao Nguyen Phan does not allow this colonial record of history to present itself as an isolated historical truth. Phan traces over Delaporte’s monochrome engravings with her own reinterpretations. She replaces Delaporte’s images of acquiescent, native servants, with beheaded, colored illustrations — the sensuous exoticism of Delaporte’s image undercut by Phan’s violent visualization of sublimation and stolen identity. These beheaded specters also reference decapitated Khmer statues, taken from Cambodia by the colonial French, and which remain “saved” in the Musée Guimet in Paris.

Phan’s recurrent beheaded figures help visualize how the Mekong’s colonial past continues to write over its present, and how colonial travelogues and narratives write out the history and perspective of their conquests. By doing so, by fictionalizing these non-fictional, black and white archives through the prism of vibrant myth and metaphor, Phan achieves a recreated reality closer to the truth. As the French filmmaker Georges Franju said, ‘You must re-create reality because reality runs away; reality denies reality’.

The final frame brings us back, pans out, to the trickling lines of the Mekong which first greeted us on the lacquer slabs. Only now, Phan has illuminated how these vast sinews intertwine the threads of many lives and stories; of the present, past and future. The destructive and chaotic power of the Mekong belies a beautifully fragile and radical interconnectedness. It is only through realizing this interconnectedness that present and future generations can save and steward the planet.

The video loops, the film is reborn, new spectators trickle in and out and yet, Becoming Alluvium’s lyrical celebration of the Mekong, and ecological warning, lingers.

Thao Nguyen Phan, Becoming Alluvium, is at the Chisenhale Gallery from 26 September 2020 – 6 December 2020. Book an appointment to see Becoming Alluvium on the Chisenhale Gallery website. Photos courtesy of Chisenhale Gallery.

NOTE: This article was updated on November 9, 2020 to attribute the contribution of artist Truong Cong Tung and architect Anh Cuong Nguyen of NhaBe Scholae.