Zheng Guogu: Visionary Transformation

VW (Veneklasen / Werner) (Rudi-Dutschke-Str. 26, Berlin), Mar 21–Apr 25, 2015

In the village of Yangjiang, in the province of Guangzhou, in the home of a musical instrument maker and opera singer, lived a youth whom nature had endowed with the most gentle manners. His countenance was a true picture of his soul. He combined a true judgment with simplicity of spirit, which was the reason, I apprehend, of his being called Zheng Guogu (郑国谷, b.1970). In 1988, a traveling magician turned the village into a town with factories, saying, “All is for the best in this, the best of all possible worlds.” Guangzhou was full of 18th-century Parisian risk and ripe with 20th-century Californian hope. The town became famous for making scissors and knives.

Around this time, Zheng moved to Guangzhou to attend the Guangdong Academy of Art. There he met the Big Tail Elephant, a group of artists—Lin Yilin, Chen Shaoxiong, Xu Tan and Liang Juhui—who through their own performance and conceptual magic questioned the world created by the magician. In the years to come, Zheng would emulate his new uncles rather than the magician. He worked and played. He built a house of experimentation called Vitamin Creative Space—now one of the most famous galleries—but he himself renounced his ownership, becoming merely one among its mendicants.

In 2002, Zheng founded “Yangjiang Group” (阳江组) with his fellow artists, Chen Zaiyan (b. 1971, Yangchun, China) and Sun Qinglin (b. 1974, Yangjiang, China). The group eschews traditional artistic practices, more often using performance and installation, yet still focusing on calligraphy, the cultural crossroads of art and poetry in China, and also philosophy and power.

I am not going to tell you the truth anymore. It would take too long and maybe it will change anyway. As Dr Yu Tsun comments: “Having read various interviews and articles on Zheng, I have some idea of some of his projects but no one has really got to grips with why he is an artist.” Hu Fang wrote an opaque poem. It is the most useful text.

Rudi

Rudi Dutschke (1940–1979) was the most famous student activist in West Germany. On April 11, 1968, he was shot three times on Kochstrasse, Berlin, by a right-wing activist following a strident campaign by popular conservative newspaper Bild and its publisher Axel Springer (1912-1985), whose offices were nearby. Though Dutschke survived, his injuries led to his early death. In 2008 this stretch of Kochstrasse was renamed after him.

It is appropriate and weird that Zheng has his first solo-show in Germany on Rudi Dutschke Strasse at VeneKlasen/Werner, the experimental studio of Michael Werner Gallery, famous for its provocative artists including the likes of George Baselitz (b. 1938), Jörg Immendorf (1945–2007), Markus Lüpertz (b. 1941), A. R. Penck (b. 1939) and, most relevantly philosophically, Marcel Broodthaers (1924–1976).

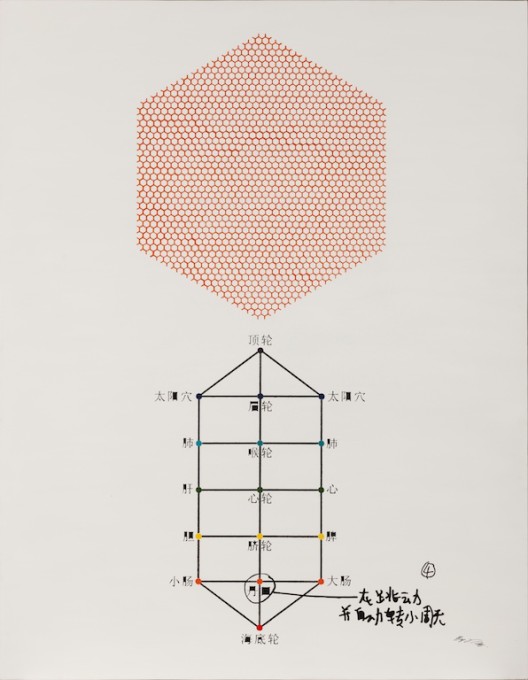

The VW exhibition introduces a recent range of objects Zheng has produced since 2000. “Impacted Chairs” are traditional Chinese chairs made of African ebony, their surface carved to resemble pitting by golf-ball sized hailstones. A similarly carved traditional wall panel comprises a piebald jigsaw of wooden pieces. “The Aesthetic Resonance of Chakra No.4” (oil on canvas, 2014) presents the Buddhist Chakra, important in tantric and yogic traditions, as a “chemical” formula. “Computer Controlled by a Pig’s Brain” (oil on canvas, 2014) is from a series dating from 2006, which extracts the “hormone” of logos and branding from popular magazines, presenting them as a distillation of thrilling, neon commercialism for mainlining consumption—endorphin-packed pleasure. Our brain is the pig’s brain—a delicacy—and thus consumerism is equated with autophagy. In a variation—“Frieze” (2014)—the data floats as hypertext over a packed bureaucratic (and Western) waiting room.

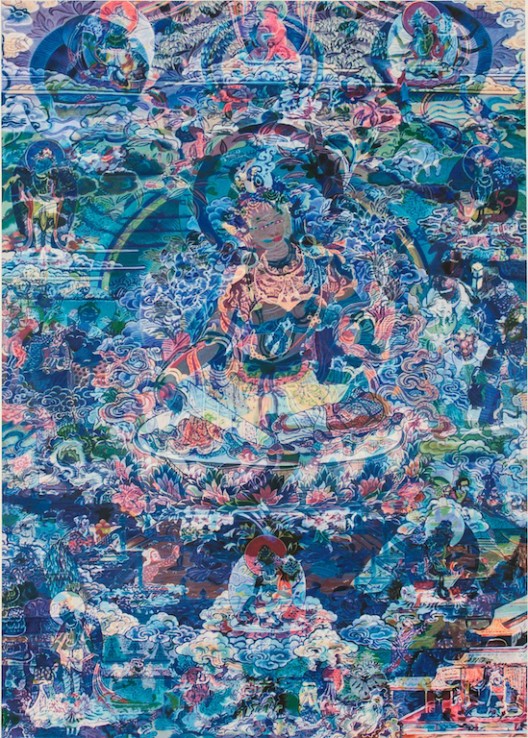

The literal heart of the exhibition is a room—a kind of temple—dedicated to a constellation of Buddhist-derived works. The real religion of both America and China is not Christianity or Communism, rather Capitalism. It is not possible to be atheist in a Communist country—always you have to believe in a god, whether Mao, Buddha, Confucius, Athena, Hobbes or Levitation. It is not important that the god exists: belief suffices. Capitalism merely describes a value-exchange system but belief makes it karma. At the center is the Buddhism-inspired “Visionary Transformation of an Insight No.1” (2012), an oil painting that mimics a photographic negative. Either side hang mandalas—“Mantra Wheel (for Career II)” (2012) and “Mantra Wheel (Liberation, III)” (2013)—and on the adjoining walls, opposite one another, classical Buddhist scenes, “One Manipulates into Two, Two Integrates into One” (Nos. 1 and 2, 2013).

Zheng designed these oil paintings. He then commissioned a specialist painter to manufacture—to make by hand—the product/commodity. Originality is unimportant; yet Zheng has employed traditional methods to produce traditional objects, elaborate souvenirs, of his artistic modus operandi. The negative mandala involves the child-like fun of optical tricks, super superficiality—nothing hidden—reading depth, formal or philosophical, where this is none. And yet it does bewitch. An “original” painting of a photographic manipulation, the dedicated quality of the copy matters. Here the copying counts more than the copy itself.

Retreat into history and tea ceremony

Defining a critical position in China is like lashing oneself to a ship’s mast in a storm. If the mast is not Communism, then at least cultural nationalism allows a nominal license to be critical. Part of Zheng’s practice is to host a tea ceremony, as he would partake at home. It is not simple but opulent, including rare and expensive teas of great age. Elegant or hubris—you decide. I am skeptical but that doesn’t matter. Take it all in context—the Buddhism, the calligraphy, the hermit-like retreat to rural Guangdong, the making of furniture, the production of painting—and all this is about defining a space for people, historical and cultural, that sits apart and in judgment against the superficiality of consumption, whether Communist or otherwise. In a monotheistic universe, Buddhism or aesthetic detachment à la China’s literati artists, or just sex and comedy, become critical systems simply by being employed as alternative systems. The Other, which they represent—because they themselves are not, and even cannot, be dominant—is a provocation to supreme egotism. Consumerism is only a symptom.

The Garden of Forking Paths

Zheng has been building a paradise in Guangzhou. It is called “The Age of Empire”. It is illegal. He has occupied the land like squatters in London do the empty mansions of rich foreign investors. It is a type of revolt against a type of colonialism. Amidst a government crackdown, ostensibly and actually on corruption, what if this is investigated? What if someone complains? Value has to be provided to the party and the community, albeit largely a self-selecting community who takes the time to travel to the outskirts of Guangzhou. Negotiation is a word much abused by curators as a synonym for “discussing” but here the artist must really negotiate, with the peasant “owners”, with local government officials, even the police. Instigation is the idea and negotiation the practice—the artistic expression splicing freedom and responsibility, social and political, environmental and communal, albeit in a self-assumed role.

One pre-2000 work is included in the show, an image from “Me and My Teacher” (1993), a project in which Zheng befriended a local beggar and followed him for a month. Under other circumstances it would be termed stalking and yet as documentation it is also a record of existence. The two are shown squatting in a public area as people walk by. They are laughing.

We could pontificate endlessly over the multiple possible meanings of each of the works mentioned so far, and others besides, not least his series of “homages” to Modernist apostles—Duchamp, Beuys, Warhol, etc.: “The Brain Nerves” (2014). Equally they can be taken on face value—the series includes “My Teacher”.

Zheng could have just stayed in Yangjiang, but he went to Guangzhou and one thing led to another. As much as he saw a world being made anew, he worked to recreate a version of the old world, idealized certainly, but also through a negotiation with cadres and collectors, between images and reality, originals and copies, hierarchies and you.

“All that is very well,” said Zheng, “but let us cultivate our garden.”