Secundino Hernández

‘All Is Too Much’

cac málaga (Calle Alemania), Feb.16-May 6, 2018

Following his 2015 show at the Yuz Museum in Shanghai, Secundino Hernández is already familiar to audiences in China. His latest museum show just opened at CAC Málaga. Here we republish a catalogue essay from the show.

“…it is impossible to do the old any more. As Malevich says, it became impossible to paint the fat ass of Venus any more. But it became impossible only because there is the museum. If Rubens’ works were really burned, as Malevich suggested, it would in fact open the way for painting the fat ass of Venus again. The avant-garde strategy begins not with an opening to a greater freedom, but with the emerging of a new taboo—the “museum taboo”—, which forbids the repetition of the old because the old does not disappear any more but remains on display.

—Boris Groys (1)

I was also living near the library in the Spanish Academy, it was very easy each day to study every artist. And I understood, more or less, that I had to develop my own language but also [to] be conscious of my [artistic] ancestors. I began a conversation, within the art, without any idea of time—I don’t care if El Greco is [from] 400 years ago or yesterday, because I think he is also very contemporary.

—Secundino Hernández

As Groys notes in the opening passage of his essay, “On the New”, “We experience art history first of all as represented in our museums.” One might add, to be glib with Marx—and why not? —, secondly as farce. (2) Groys builds on this to argue against the inherent limitations of Avant-gardism. Groys is drawing a metaphor between museums and catacombs; a citadel built on the remains of the dead and thereby eventually ossifies its inhabitants. There is a certain masochism to this. It is a very pessimistic, sort of seductive, view of art. This is not to say it is wrong but rather only sometimes right. One problem, put simplistically, is that the medium of art includes artworks; the canon. Modernism—and its romantic lovechild Post-Modernism—have been enthralled with progress, with developing new “languages”, but the languages themselves become more media: media becomes medium. The ass of Venus is anybody’s.

Dis(as)semble all over

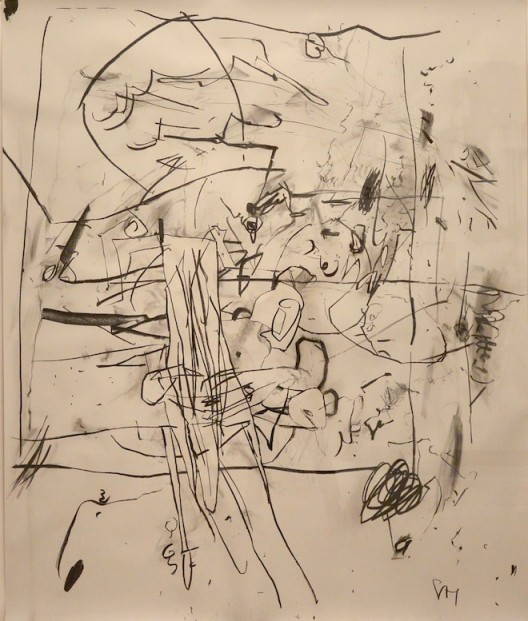

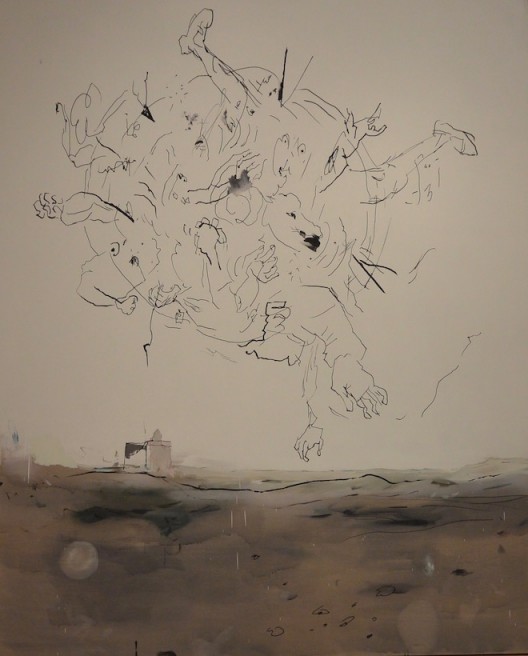

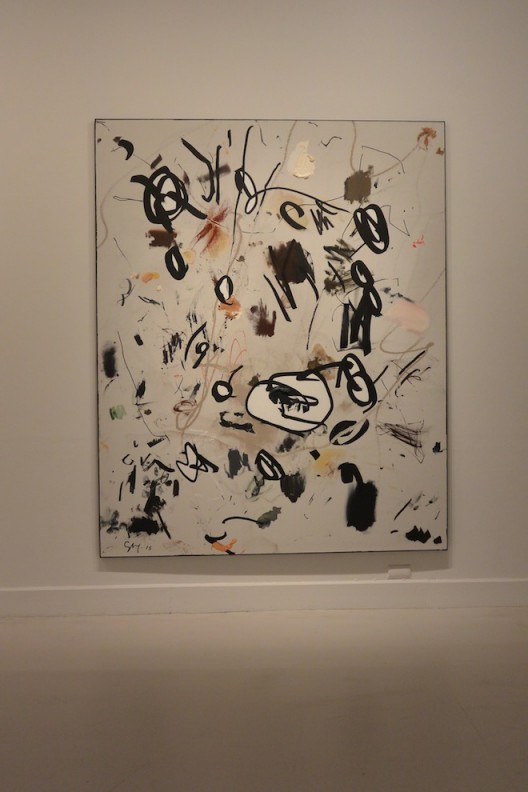

Lines fly across a canvas, violently, chaotically, obsessively and orgasmicly—extraordinary how anthropomorphism attaches to descriptions of drawing, of mark making: an expression of being through mute signs. The ground gesso has been removed, scored, scratched. Paint strokes are wiped and smudged. Some trailing spatters have somehow even been removed. Sometimes there are scuffs from a shoe, the paint-pot’s own footprint, dust and detritus. Sometimes the paint tube is used like a graffitist’s thick oil pen, or lyrically, calligraphically, like a quill. Cartoons—color filed outlines—appear and disappear. There are murmurings from so many different artists: Salvador Dalí, Jackson Pollock, Cy Twombly, Antoni Tàpies, Paul Klee and Juan Miró, and older ghosts, El Greco, Titian, Michelangelo. Half-figures and heads emerge when the disparate marks and lines are brought together in the mind’s eye, like a star’s constellation becomes the Great Bear or Sagittarius—note well, here, Hernández’s Apostole’s series after El Greco. Warning, though: it is only a half-respectful raid on art history. Everything can be taken and used, and this makes the carnage beautifully thrilling.

If Groys is right and contemporary art is in a state of auto-cannibalism, a religious obsession with its own body that traps it in its past, then the more self-aware artists are like forensic pathologists, admittedly with a want to use the parts for art. To look at art, to gaze at it, involves its destruction—its pulling-apart, its dismemberment. And eventually, also rearrangement. It’s what makes Mary Shelley’s monster such a romantic figure, a creation for the future whose past is already history—dead. The line between reality and dreams is precipitous, space and time. This is crucial. The marks on Hernández’s canvases are marks in space but also with space. They are explorer’s maps for travelling through art.

Bacchus and Ariadne

In 1520 Titian (Tiziano Vecelliio, 1490?-1576) painted “Bacchus and Ariadne”. Now in the National Gallery in London, it is a giant work, 176.5 x 191 cm, originally commissioned by Alfonso d’Este, Duke of Ferrara for the Ducal palace. It depicts the meeting of Bacchus and Ariadne, after she has been abandoned on Naxos by Theseus. On sight Bacchus falls in love with her—in the painting, unsurprisingly, Ariadne appears nervous but the sky includes the star constellation to which Bacchus would eventually raise his muse. The most curious thing about the scene is Bacchus, who leaps from his chariot but whose stance does not accord with the rest of the picture plane. This was probably prompted by the difficulty of getting a model to hold a realistic “leaping” pose but Titian was hardly limited by such circumstances—witness the hovering cherubs in the “Rape of Europa” (c.1560-62), in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. No, from a formal and philosophical perspective, what is fascinating here is how Titian directly confronts the “space” of painting. Bacchus is simultaneously in the world of Naxos and in another space-time continuum: in the world of the gods. We could say it illustrates certain possibilities of quantum physics; much as Christopher Nolan’s 2014 film ‘Interstellar’ does. Painting can depict multiple spaces and times simultaneously and in multiple and contingent ways. This is the nature of their physical construction, the mechanics of their imagery and symbols as determined or made by the artist, and, with a nod to Roland Barthes and Jacques Derrida, how we read them. Bacchus leaps in spaces—the island of Naxos, from chariot to Ariadne, the world of the gods, the starry sky, and the painting itself, the stretched canvas, the obliterated cartoons and the overlapping layers of oil paint. Perhaps this is a conceit, yet it lies to a greater or lesser degree in all painting, whether“Cranes over the Palace” (1112) by Emperor Huizhong (1082-1135) in the Song Dynasty or “A Bar at the Folies-Bergère” (1882)by Édouard Manet (1832-1883).

Now let’s take a leap in time and space ourselves. Think of Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. In the early 21st century, notions such as non-objective art, abstract expressionism, and all-over painting, seem almost tamely familiar, operating to mark and separate certain developments in art history. Yet as Michael Fried has demonstrated, if somewhat dogmatically with his own concepts regarding theatricality—very simply, the elision of a painting’s own materiality, turning it into superficial performance—, issues of the interpretation of the space of a painting have existed throughout history and naturally enough persist with the art of such figures as Pollock and de Kooning. In other words, painting is not merely illustrative but exists independently within the world of things and in terms of the “spaces”—possibly conflicting—within itself.

In Pollock’s All-over paintings exists the space of the surface, both two-dimensional and three-dimensional, and within any designated area of the painting, and between the ‘strokes’ themselves. With de Kooning there is the infinite stroke, where hue and paint flow over and under, and back again, linking surfaces, and thereby time, folding over itself, again and again, and obtaining a phoenix-like renewal through repeated destruction. It was these artists who realized that there is an explicit conceptual space between overlapping brush-strokes, which dive under and over, thinning and then thicken, change colour, and accordingly depth, or its perception. It can be expanded in all directions—hence the “All-over”.

What we see before us

Visual space does not replace or traduce the so-called three-dimensional space that our bodies occupy and move around in, the space that exists regardless of whether we do. Visual space is our space, we read it so far as it is interpretable, and experience it both actively and passively. Often it commands our attention, but just as often its umpteen characteristics, we ignore. It seduces us, or we let it do so, and this is not a fake experience, something trivial, but an everyday aspect of life. Imaginations and visions are a real—absorbed in the moment, deluded, charmed, fooled…all of this is real. Its role in art is not at all new. It exists as much in Titian’s “Ariadne and Bacchus” and in Leonardo de Vinci’s studies of moving water, as in the carved wood totemic and chromatic figures of New Ireland in Papua’s Bismarck Archipelago.This is the space in which Secundino Hernández plays with—and out—the possibilities of painting and its potential spaces.

Drawing and painting

Painting, loosely defined, is the application of pigment to a surface, whereas drawing is the pulling out of a mark. It may be a line or a mark but Georges Seurat (1859-1891) shows that it could as easily be a hazy smudge. Ultimately though the distinction is ambiguous and arbitrary. And it matters little, except in the relations of meaning developed between the two ‘practices’, notably exemplified by Cy Twombly (1928-2011). What is missing from how we discuss these seemingly diverse threads, is how different elements can be put together in a single story, much as a Kanye West or Frank Ocean might with music, and yet still acknowledging the wider sweep of thousands of years of practice in painting and drawing.

Among the artists who play in this arena today are formal conceptualists such as and Christopher Wool (b.1955) and more recently Wade Guyton (b.1972), and the performance derived art of Katharina Grosse (b.1961) and controlled explosions of Julie Mehretu (b.1970). Yet none address the canon as both space and media in itself. This however is one of the most fascinating aspects the work of Secundino Hernández.

Painting and drawing are different registers in closely related—even overlapping—tunes. The mark itself is not important—too great an obsession with mark making reeks of an antediluvian fetishism. A quality of a drawing is defined by what is left out, whether space is filled or left empty.But the experience of these relations is contingent and shifting, and this uncertainty creates the visual dynamism that drives Hernández’s compositions. When pigment—color/matter—is applied to a surface it is also applied to a space. Two-dimensional drawings and paintings are made and exist in three-dimensional space, and we can think of a stack of pictures as somehow like a flipbook of space and time.

Hernández’s paintings and drawings record how they are made—the smudges, the scratches, the stains, acknowledging the relation of the painting within the “real” world but also in its making, as a thing brought into existence by an artist—but these are subsidiary themes to how space is defined by line and color. In “No hay verano sin ojos”(2013) a form—figurative?—floats on/above a stage/landscape, the latter, note well, defined by an “out-of-focus” horizon/ground. The relation itself is defined due to the sharpness of the composition of the forms—black droplets, scrawled lines and white cartoons—“in front” of the horizon. Meanwhile, in “Untitled”(2013) [**HERN/M 36] the horizon has virtually disappeared; hinted at only by a few loose lines underneath the explosive mass of black lines floating above. “Sky” and “ground” are both white, thus existing in an almost undefined space (a few flecks of blue streaking through the cloud of lines hints at a heaven or vapor trails). Long stretched-landscape works, such as “Untitled”(2014) [**HERN/M 56 ] force us to “read” the composition from one side to the other. Some like “Untitled”(2014) [**HERN/M 61 ], with its geometric funnels, appear almost anachronistic, and this is quite deliberate, because the disjunction between space and time, painting and history, is exactly what interests Hernández.

Compare these graphical works—for want of a better description—with the colorful thick impastos of paintings like “Untitled” (2012)[**HERN/EX 15 ] or “Into your eyes” (2013). On first acquaintance, these works seem to be in a quite different register to Hernández’s more graphic oeuvre. Yet the issues are the same. Here, color (mass) dominates the canvas (space), so weight and color take precedence over line and time. These works are less numerous than their counterparts but the relationship between the two sets is key to their interpretation. In a way, the impasto paintings are close-ups of areas of the graphical works (see for instance, the cross-over “horizon” work “Untitled”(2014) [**HERN/M 46 ] combining elements of both)but they also emphasize that color does not play a secondary role in any of the artist’s works. Even small marks or areas of blue or red accent the relationship between line and space.

The space of an area of color is quite specific: a large, unbounded area of one hue or shade, such as a light grey, has a totally different effect to a cartoon form filled with white, pink or blue. In “Untitled”(2013) [**HERN/M 37 ] a central burst of yellow is brighter precisely because it is stationed centrally in the top third of the picture surrounded by relatively darker areas of red, blue and green. The overall mass of impasto paint “floats” on the raw canvas, with small marks hinting at the connection to the graphical works (by contrast, “Into your eyes”, literally fills the canvas, paint crowding to the very edges abutting the “real” world in which we view the picture). In an exhibition, the impasto works perform the role of visual counter-weight, including specifically for the visitor, who must acknowledge the physical relation of difference, in space, hue, weight and line.

Looking closely, it seems that the cloud of gestural marks and grey cartoon-clouds of “Untitled”(2014) [**HERN/M 57 ] might be the blueprint or X-Ray of the impasto “Untitled” (2013). Whether there is a connection or not is unimportant: again, the relation between the impasto and graphical works is what is significant. When we return to the latter—including works with a dark background, such as “Untitled”(2014)[**HERN/M 62]—, as the eye searches to recognize things in space,works like “Slowly taking place” (2013) and “Untitled”(2015) [**HERN/EX 29 ] appear to adopt previously unremarked forms—a hand, poles, a figure falling. In the paintings that emphasis the surface of the canvas centrally, such as “Untitled”(2015) [**HERN/M 65 ] and “Untitled”(2015) [**HERN/M 67 ], even the “non-space” of the raw canvas becomes real, embodying form, and visually receding or advancing within the compositions.

Everything one needs to have an understanding of Hernández’s drawing-paintings exists inside them. Each one comes with its own toolkit of ideas and manual to read. It takes only a little patience and time. I started out by discussing the historical machinery that is present in the paintings, issues of time and space, and proceeded to the mechanics of the paintings themselves, their line and form, color and weight.

I want to return to what I was saying about El Greco and Picabia, because it is difficult to explain. What I paint is the painting painted but also the painting lived—“lived” like a spectator. So I paint where the paths cross, not only as a spectator but as an artist…

These paintings are not dictatorial or pedagogic. They do not profess to invent a new language or foist one upon us, let alone the artist’s own “language”. They explore what exists already in painting, in image making. Hernández is not seeking to adopt, coopt or steal the past but to delve into the formal and physical relations that link the history of painting and our ways of understanding it, including who we stand in physical relation to pictures, in space naturally, but also in time, ours personally and that of paintings gathered collectively through the centuries in museums.

I am conscious that I am coming from somewhere. I am respectful of the European painting tradition. I can’t pretend to come from nothing. More and more though, I am not so interested in this kind of interaction with other artists. At the end, it is only a pretext to go on with your works. I like the idea of how music was made in the ’60s, when people were sharing compositions, and you could have the same song played by The Kinks and Bob Dylan and others. That was nice, because everyone was playing the same music but in their own style, without any “complex”. Nowadays everyone tries to be original and some guys complain that, “everyone wants to copy my ideas”. Come on! It makes no sense! Everything is already invented! You can only offer your own perspective, your own filter of the whole thing.

Chris Moore

Berlin, February 2016

All quotes by the artist taken from “Between Line and Color: Secundino Hernández interview”, Chris Moore, randian-online.com, 2015.10.09

Notes

1. “On the New” December 2002. https://www.uoc.edu/artnodes/espai/eng/art/groys1002/groys1002.html (accessed 28 February 2016).

2. In his 1852 essay, “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte”, Marx noted that, “Hegel resmarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.” https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/18th-brumaire/ch01.htm