This review is included in Ran Dian’s print magazine, issue 3 (Spring 2016)

There’s something funny about memory: the further a moment recedes in time from the present, the rosier the recollection becomes, the less complicated it seems, and, with the benefit of hindsight, it becomes easier to understand. In psychoanalysis this phenomenon where an individual forgets negative emotion faster than pleasant emotion is known as the “fading affect bias.” (1) In Freudian analysis, it is linked to the repression of trauma.

In looking at the legacy Martin Wong’s work, one is struck by what many of his critics have described as a naïveté enacted, for example, in the way the late artist rendered thousands of minute bricks on the many façades and frames he painted, or his almost cute, cartoonish depictions of subjects ranging from firemen to former lovers to street scenes of the bi-coastal Chinatowns he came to know. (2) This goes further to affect the way Wong’s oeuvre is re-presented to audiences today: he had a rich and multifaceted life, and has very recently become an emblematic figure for many different communities and social dynamics. He represents a time that America’s art history is still coming to terms with: the trauma of the not-so-distant past. Meanwhile Wong, as an artist and as a man, has grown ever more enigmatic as his art and the world he depicted drifts further away from the world of today.

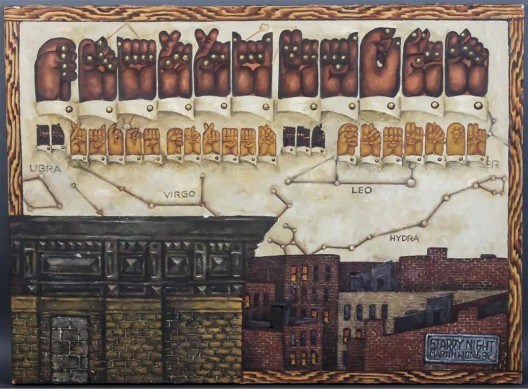

Martin Wong, “Starry Night”, oil on canvas, 56 × 76 cm, 1982 (Bronx Museum of the Arts, Gift of Suzy and Joseph Berland)

During his lifetime, Wong received little attention from the art world and the press. When compared to his contemporaries, who included Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and even the young Ai Weiwei, all of whom were living in Manhattan during the 1980s, Wong seems to have been a peripheral character, if not an outsider, or even, at times, a self-described hermit. Indeed, this is part of Wong’s current allure, since his critics and the contemporary art community are still in the process of “discovering” him and his work. Yet Martin seems to represent more. Over time his identity has become malleable, able to fit into narratives cast by curators and social activists alike. Today, Wong the man and the art he produced could fit into any of the following categories:

Asian American

Chinese American

Immigrant

LGBTQ

“Outsider” Artist

AIDS victim

Chicano/Latin American

Hippie

Graffiti Art

Social Realist

New Yorker

San Franciscan

Lower East Side

Chinatown (NYC and San Francisco)

Northern Californian

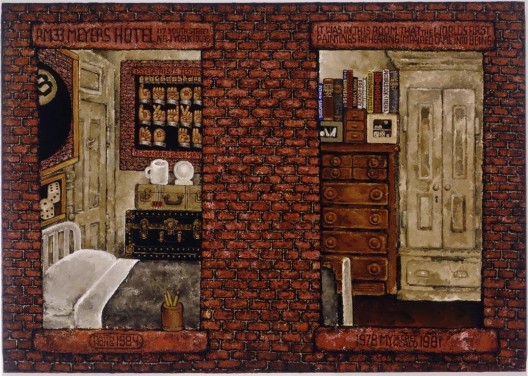

Take any of the recent exhibitions featuring Wong’s work as an example, and you will see this process of categorization and appropriation unfolding. In the Bronx Museum of the Arts’ “Martin Wong: Human Instamatic” (2015) Wong is cast almost solely as a New Yorker. His “My Secret World, 1978–1981” (1984), a highly detailed vignette of the artist’s room and first residence at the Meyer’s Hotel, weaves him into the gritty fabric of the city. Other pieces, such as “Attorney Street (Handball Court with Autobiographical Poem by Piñero)” (1982–84), seem to elegize a world that no longer exists: the brief moment of the late 1970s to early 1980s when neighborhoods like the Lower East Side were hotbeds for the dual forces of urban decay and impending gentrification, a time when the city’s government was too bankrupt to pay for cleaning graffiti. Wong’s image of the handball court thus becomes a theater for this drama. The visual schema, with the vertical forces of the concrete handball wall adorned with graffiti (a tag by one of his friends), the angles of the surrounding chain-link fence, and the brick tenement buildings looming in the distance seem to reinforce this “theatrical” quality of Wong’s vision. Even his fleshy American sign-language letters (which are ever-present in his works of this period) seem to serve more than just their didactic role: they become a human presence in an otherwise barren stage.

Other imagery shown as part of “Human Instamatic” likewise helps situate Wong in his adoptive community of Manhattan’s Lower East Side. “El Caribe” (1988), an unconventional portrait of a friend and member of a Puerto Rican motorcycle club, highlights a milieu of pastiche, kitsch, and appreciation that Wong infused into his work, presented through the dutiful painting of El Caribe’s leather motorcycle jacket and his perfectly framed portrait within his side mirror. Similarly, his 1988 “Big Heat”, which depicts two firemen locked in a kiss, portrays the ruins of a tenement block.

Here, the trauma of the everyday (urban squalor and decay) is juxtaposed (though in no way put in conflict) with Wong’s fantasy of two firemen kissing. The visions seen in both “El Caribe” and “Big Heat” are potent and, for those who try to situate Wong amid the social and historical dynamics of New York during the 1980s, can be used to reflect the artist’s own homosexuality and his participation (albeit often as an observer) in the diverse and fragile community of the Lower East Side.

Other recent exhibitions have tried to give a broader and more nuanced picture of Martin Wong. P.P.O.W. Gallery in New York, which oversees the artist’s estate and has been featuring his artwork since 1985, recently staged “Voices”, a collection of many of Martin Wong’s distinctive calligraphy works as well as some of his early ceramic pieces. The works here were drawn almost entirely from Wong’s earlier life, from the mid-1960s up to 1978, spent in San Francisco and Northern California, showing how different and by no means less developed his artistic practice was during this time.

The calligraphy, which sometimes appears on scrolls, vellum, or unraveled brown paper bags, displays a dynamism of form that is purely Wong’s own. Superficially these works may appear to mimic classical Chinese writing, as in his scroll-like piece “Sewer Goddess” (1967). But Wong’s work, which is frenetic and jagged, also borrows from the then-contemporary forces of psychedelic and emerging “low-brow” art, for instance the works of contemporaries such as R. Crumb or the promotional posters of the Family Dog. His early painting and ceramic pieces, including the 1974 acrylic on canvas “Weatherby’s” or his ceramic “Untitled (Winged Coca Cola Plaque—Psychic Bandits)” (1971), seem to reinforce this affiliation with their bulging forms. Wong often mused that these were influenced by his own relationship to psychedelia and the art of the hippie counterculture. (3)

“Painting Is Forbidden” (2015) at the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts in San Francisco continued in this vein, utilizing a mixture of Wong’s early calligraphy, ceramics, and several of his mid-career works depicting the Lower East Side to cast the artist as an individual whose life and practice was at the intersection of a diverse array of cultural and historical forces. Additional archival material helped to reinforce his San Franciscan roots while also celebrating him as a local of Chinese American origin. The Chinese Historical Society of America Museum of Art in San Francisco did the same with their “Taiping Tianguo: Martin Wong’s Utopia” in 2004, which marked the five-year anniversary of the artist’s death from AIDS. (4)

Martin Wong was a storyteller, often prefacing descriptions of his works with quips like “There’s a long story to this painting,” before going into versions of his autobiographical account of the details behind the scenes he’d craft. (5) The images he created told the stories of people who populated the streets he knew and the varied and (at times) fluctuating relations he had with them. These were stories of lovers, of tenement dwellers, of graffiti writers, of firemen, and of parents he wasn’t fully ready to come out to. His painted visions were imbued with a sense of fantasy, perhaps since Wong always kept himself at a calculated distance from many of the subjects he chose to depict, and this often meant that his keen observations gave way almost seamlessly to his vivid imagination. (6) There is a tinge of the bittersweet in these images, from his painted text “I Really Like the Way Firemen Smell” (1988) to his Chinatown urbanscape “Wong Family Benevolent Association” (1990). The distance he kept (physical, geographic, emotional) from these subjects seems to reflect a sort of unrequited quality that Wong always felt among the many forces of his own identity.

In a symposium talk he gave in 1991 at the San Francisco Art Institute, Wong stated that when he painted New York’s Chinatown, he did so from life, whereas when he painted San Francisco’s Chinatown, he worked from memory. (7) Here there is something of a parallel that is worth mentioning: in the somewhat campy, warmhearted, almost exotic images of the San Francisco Chinatown of Wong’s childhood, we see a vision through the rose-colored filter that memory affords. Now, after more than three decades since he started painting Manhattan’s crumbling yet bustling Lower East Side, we as observers likewise can’t help but see something charming amid the dilapidation. While he wasn’t always at ease nor fully immersed in any single identity, Wong’s life and the past he depicted has, in some way, helped his current audience come to terms with the traumas of a chapter in American history: a time when cities began to push against the poverty within them, when being homosexual was something to be both hidden and fetishized, and when AIDS could destroy entire communities in the course of a year.

This tendency of the art world (one in which it is not alone) to celebrate someone only after they are dead, and especially if they represent forces that were once deemed “peripheral,” “dangerous,” or “unapproachable,” seems to be an unspoken aspect of Wong’s legacy. His life amid the blurred territory of American subcultures and multicultural milieus ensures that he stays a complicated figure in contemporary art, one for whom it is difficult to qualify one identity without possibly disqualifying another. As a result, and with each new presentation, Wong’s art and his personal story have themselves become a melting pot for contemporary art historians, critics, and the public as representative of the nebulous character of identity politics, while also serving to address complicated, often traumatic, collective memory.

艺术博物馆提供)/ Martin Wong, “Tell My Troubles to the Eight Ball”, acrylic on canvas, 91 × 91 cm, 1978 (Collection of KAWS, New York; courtesy the Bronx Museum of the Arts)

Notes

(1) Saima Noreen and Malcolm D.MacLeod, “It’s All in the Detail: Intentional Forgetting of Autobiographical Memories Using the Autobiographical Think/No-Think Task,” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 39, no. 2 (March 2013), 375–93.

(2) Peter Schjeldahl, “City Scenes: A Martin Wong Retrospective,” New Yorker, November 16, 2015, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/11/16/city-scenes.

(3) See Charlie Ahearn, “Martin Wong Portrait 1998,” https://vimeo.com/152493246.

(4) Mark Dean Johnson, “Taiping Tianguo,” in Taiping Tianguo: A History of Possible Encounters, ed. Doryun Chong and Cosmin Costinas (Sternberg Press, 2015), 106–7.

(5) Caitlin Burkhart, “It’s Easier to Paint a Store if It’s Closed,” in My Trip to America by Martin Wong, ed. Caitlin Burkhart and Julian Myers-Szupinska (San Francisco: California College of the Arts, 2015), 101.

(6) Amelia Brod, “Watusi in San Francisco,” in My Trip to America by Martin Wong, 119.

(7) Caitlin Burkhart, “It’s Easier to Paint a Store if It’s Closed,” 98.