by Chris Moore 2018.09.25

Undercurrent voices: an interview with gallerist Rachel Lehmann on how she became a gallerist, the artists she has worked with, Korea and Hong Kong

Sitting at a small table in the Lehmann Maupin booth at Art Basel Hong Kong, Chris Moore spoke with Rachel Lehmann about how she became involved with art, galleries and Hong Kong. It was Saturday afternoon and the booth was very crowded. There were constant interruptions from visitors, friends and staff, with David Maupin’s voice constantly in the background, on the phone or chatting with a collector.

Chris Moore: How did you become involved in art?

Rachel Lehmann: Oh my god! I actually started by writing poetry. I was very young, I don’t know if 13, expressing myself through writing. So it was terrible! My parents were collecting—not really collectors but collecting—old Meissen porcelain. So I didn’t get the support [for artistic pursuits]. I threw everything away but…

CM: —What, you threw away the Meissen or the poetry?

RL: I threw away the poetry! As a matter of fact, I started writing again recently, 6 months ago, first just reminders, and it turned into taking notes, and I realised how much satisfaction it gives me. So it really was poetry which got me started. Secondly, I was in high school in Germany, in Frankfurt. This is Germany not so long after the Second World War and there was a vacuum between history…let’s say from 1920 to until the Second World War. They were not yet prepared to talk about the Second World War up to the present. And I got very lucky. The teacher we had used to take us to artist studios instead of giving us current history. So, I think I had a need to do something which was coming from a different place. I was very visual. I was born in Ethiopia, in Asmara, where I’ve seen a lot of colors, a lot of beautiful sceneries. I grew up there.

CM: Why were you born and grew up in Asmara?

RL: My parents got married in Berlin. They wanted to live an adventure and leave behind Europe and the Second World War. They left for Asmara. I started elementary school back in Germany. They left because Mengistu was gaining power in Ethiopia. [revolutionary and dictator of Ethiopia 1977-1987]

CM: So, your high-school teacher would take the class to artist studios — any particular artists?

RL: I don’t even remember to be honest. A lot of young artists. It was an interesting moment in Germany because a lot of intellectuals either [had] died or left during the Second World War and that vacuum was filled with visual art, as you know, from Baselitz to Kiefer to Richter, all of these artists after the war, these people who were feeling this kind of need. So this is how I got interested [in art]. So when I finished high school I told my parents that I wanted to go into the arts. And they told me I was completely crazy. They said, why don’t you do something that makes more sense and do art more on the side. They were basically pushing it away. So I did political science and economics in Switzerland but I remained super interested in the arts. I was selling shoes in the summer to buy a little drawing and I started travelling in the summers to New York, because you have to imagine that Switzerland, at the time, really didn’t have any international contemporary art, and I was an international person who wanted to see outside the Swiss landscape, the contemporary art landscape.

CM: Hard to believe today.

RL: Totally hard to believe! So this was how I got to know some of the major galleries at the time, like Sonnabend, and in France, particularly Paris, Paris was the big city to the small provincial country like Switzerland is, or was at the time. And I started working with a gallery that is not there any more [Gallery Monténèy Giroux], which was run by Marie Helene Monténèy, and I was very close to Mrs Sonnabend [Ileana Sonnabend, 1914-2007], whom I am sure you know by reputation, and who in the 70s had a galleries in Geneva and in Paris.

CM: She was really ahead of her time.

RL: Oh absolutely ahead of her time! It’s so interesting: people remember the Castelli brand but she was, well because she was a woman…

CM: Well really, she educated him.

RL: That’s what I would like to say! So, this was the 70s. I did not see the gallery in Geneva but I did see the gallery in Paris. But the big thing for me was New York. I used to arrive on Friday afternoon and go straight to Soho and look at the galleries. I didn’t study art history. I never went back to school. I read vividly, I looked vividly.

I knew that I wanted to go to New York at some point. I was offered a job at Chemical Bank – it doesn’t exist anymore! – [and moved to New York]. At that time I met my husband [Jean-Pierre Lehmann] at the Sonnabend gallery. He had an office in Geneva, he was working at the time managing the holding of Edmond de Rothschild, and he was looking, for a tax specialist. Now, I did political science and economics, and I was going to do – I never did it I just started – a thesis about Luxembourg as a tax entity at the time. About taxes and companies. Which obviously, it was not meand I let it go! But somehow he was talking to someone and saying he needed someone with a tax background for Geneva. And they said, well you know there is this woman there, she should is an expert! So they introduced me and I was dying laughing, I was Noexpert! No idea about taxes! But this was how I met my husband. This was a long time ago! This was end of the 70s. Finally, he said, Rachel, come! So we moved to Switzerland, got married. My husband was collecting art already. So this is bringing me exactly to 1980 when I start collecting with my husband. We were both travelling a lot and we were buying in New York. At the time we had a feeling that Europe was ‘second class’. We had crazy things. We had a 16th Century / 18th Century apartment in Geneva. You have not seen an apartment with such audacious things! And then in 1988 my neighbor, Christian de Saussure, do you know?

CM: —as in the linguist-semiotician?

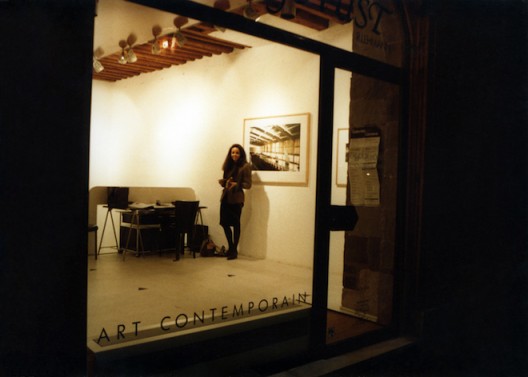

RL: Yes! The same family! Because you have to understand that Geneva was a very Calvinist place with little understanding for the arts. They hated contemporary art! [But] this family had a different attitude because they came from a different background, of philosophy. And that family wanted to have people around them [who were different]—because we were renting a magnificent apartment in one of their buildings in the old town and he was my neighbor. That same guy told me, ‘You know this gallery in the old town? The owner is called Faust and is leaving for two or three years to South America. She is looking to sublease it—why don’t you rent it and do a gallery? That’s all you do anyhow all the time!’ And I remember sowell my husband standing there and saying ‘Don’t do it, don’t do it, you’ll regret it, you’ll regret it!” Obviously, me being me, I said, “OK, I’ll do it!”

That was ’88. …That is the story. If you talk to a psychiatrist, the psychiatrist will tell you probably nothing is by chance. For me, I was in the arts because I couldn’t do anything else, because I was marginal and miserable. I found a fulfillment in the arts I could not find in anything else. …So the Faust Gallery became Lehmann Gallery in Switzerland. …My first show was a Swiss artist whom you might know, his name was Not Vital.

CM: Really, that was your first show?

RL: Yes. And we showed artists from Wim Delvoye, to Candida Höfer, to Jeff Koons, to David Salle. I showed a lot of great, great artists that nobody understood.

CM: David Salle still shows with the gallery, doesn’t he?

RL: So David Salle was partly how I met David Maupin. I later created a partnership with Metro Pictures and we had a summer gallery called The Offshore in East Hampton and David was working for us as a director. So I worked with him over three summers. He was working with us and he was working for Genny Götz, the Götz foundation, and having left Mary Boone. Anyhow when we opened the gallery in New York, we started to show David Salle in partnership with Gagosian.

CM: You opened with David Salle?

RL: No. In New York we opened on Greene Street with a show called “Moving Structures’ and it had artists like Wim Delvoye, Richard Artschwager, Carroll Dunham, and Tony Oursler.

Later on, we were obviously looking for artists. This is how I discovered Do Ho Suh, this is how I started working with Shirazeh Houshiary in the US, because many of my artists from my gallery in Switzerland were taken in New York. So I went into a partnership with Gagosian for David Salle and I went into a partnership with Sonnabend, at that time, for two artists, which were Gilbert & George, whom we now represent in the US, and Ashley Bickerton, who we now represent internationally. So Mrs Sonnabend died and Antonio Homem closed the gallery.

David Salle had decided to leave both galleries to show with Mary Boone. Then, many, many years later, we are obviously showing David Salle in Hong Kong. Life goes around.

CM: I’d like to move on to China and Hong Kong. What were the motivations for opening in Hong Kong?

RL: The mission of the gallery was always to show interesting artists from all over the world. That goes back to Do Ho, to Lee Bul, to Mr., to Shirazeh Houshiary, Gilbert & George, Adriana Varejão, and so on and so on. We were looking first to open an international gallery in Europe. We realised very soon that there was no reason for us to do something in Europe. We were thinking about Berlin but we quickly realised that the galleries that were already in Berlin would do a better job and a quicker job with our artists than we would ourselves. So the second idea was to do something in Asia, which made complete sense because we had Asian artists and we had been going to Asia since 1980—I remember when we had the show with Gilbert & George, we visited the Toyota Museum in Japan – it doesn’t exist anymore, it was Toyota, the car company. David Maupin also has quite an international background. His husband is Italian [Stefano Tonchi, editor-in-chief of Wmagazine] and when he was a high-school student in Los Angeles, he lived in Japan on a student exchange program. So going to Asia was for us related to the fact that we work with artists all over the world and we are very deeply interested in Asia but also that we had very personal connections. So the question is why Hong Kong and China, right?

CM: As opposed, for instance, to Tokyo.

RL: A couple of things happened in Hong Kong which made us take this decision. The infrastructure was easy, the language was English. You could do business in English. It was the door to China, which is the biggest area of growth and culturally one of the most interesting parts of Asia. You had M+ already in discussion andyou had Art Basel Hong Kong. So it made sense for us that, if we wanted to be active in East Asia, Hong Kong would be the right area. And it was becoming a hub for Western galleries. We had, in particular, something to add to the scene. We took a decision, which I insist was the right decision, not to create a program which is only for Asia or only for Hong Kong. We showed basically all the artists of the gallery. So our message was very clear, very loud and very consistent.

CM: You also have a very strong connection to Korea with your line-up of artists and Korea is the other major place where contemporary art is really strong in East Asia.

RL: We were looking to show interesting artists who work with several mediums. I like to talk about ‘contemporary culture’, rather than ‘contemporary art’. I was looking around and I saw a group show at Yale Universityand I really loved the language of Do Ho Suh. I remember the work very well. It was called ‘Someone’. It was a wallpaper. From far it was abstract, and near it was small figuration. It was about the idea of the group and the individual. I hopped on a plane and went to Korea. That’s how it happened, because his message was so strong and fitted so well into what we were trying to do – multimedia, international, contemporary culture, fresh! And then from there came Lee But and then I started going a lot [to Korea]. It was fascinating! Korea was not at all ‘on the map.’ Tourists were not going to Korea.

This has obviously all changed, and we opened a viewing office in Seoul in December 2017. We recognize the importance of expanding our presence in Asia — not only to maintain relationships with our artists there, but also to develop them with collectors and curators.

I became fascinated with the earlier period of Korea as well, and the influences between China, Korea and Japan, which were unknown to me. …We have been working for a long time now with the younger generation, so we are now [also] working with the older generation. As a matter of fact, we will have a show of Do Ho’s father [Suh Se-Ok, b.1929]. He is already well known. He had a show at the Museum of Modern Art in Seoul. He is an ink painter. We will have a show with him in September of 2018. And Kim Guiline (b.1936) also suits perfectly with what we are doing because he himself is international. He lives and lived in France, in Paris.

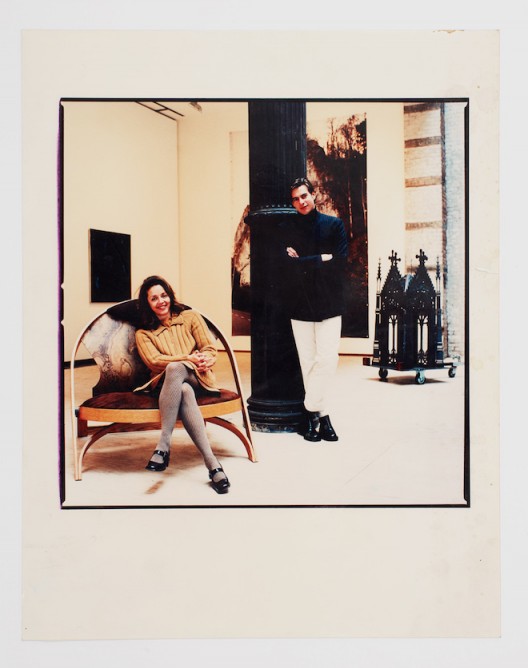

Rachel Lehmann, Lee Bul, Lee Bul Opening at Lehmann Maupin, 2010

CM: Final question. Among the strengths of the gallery is very strong female artists — at least half the program. At the top of the market, that puts you in a very, very rare group. I think only Victoria Miro is doing something similar, even if not quite the same. But at the same time, it is not something you shout about, you just take it for granted. I remember a show at frieze [London, 2015], where every single artist on display was a woman. Was it a deliberate strategy or something that just quietly developed?

RL: We were always interested in groups of undercurrent artists and different genders. So artists who were quietly committed and who needed to be heard. The female artists, because of stereotypes, have been very often working for longer, in a quieter way, and in a more committed way. It became clear to us that there is a larger group of female artists who work in this way and are working alone. So those were voices which were important, which were there but which were not heard. So those undercurrentvoices which really underline—I like what you called—the ‘shouting voices’. It’s the undercurrent line which really opens up borders for the ‘shouting’ voices. This is exactly what we did. And we were interested in it! Mickalene Thomas, for instance, is an artist we have worked with for over 10 years. Her work uses very complex art historic references, intertwined with her own history. We knew she was doing something very important, and the institutional recognition has followed with numerous museum exhibitions in the recent years. I’m happy to say, she will have a museum exhibition in Shanghai in 2020! Now today, we encounter quite a lot of collectors who particularly want to collect women artists because they know that their prices are lower. They know that a lot will change soon.

Ran Dian 燃点