by Chris Moore 墨虎恺

On a chill, sunny day in February, I visited Gregor Hilderbrandt’s studio in an old brewery in Wedding, a working-class suburb of West Berlin. A string of rooms are packed with seemingly every material and detritus possible. In the main room, a large workbench takes up most of the space. It is covered with works in production, paper, glue, books, cassette tapes, exhibition models. Other works lean against the walls surrounded by notes and photographs. There is barely room for the assistants. In front of a window stands a Hifi-Tower next to a high set of shelves brimming with videotapes and LPs—music plays constantly.

Gregor arrives, wearing dark jeans and jacket, and an un-tucked stripy business-shirt. He is tall and there is a crumpled elegance to his movements, an impression aided by a foppish haircut. He strikes me as a cross between the suave agent in the film “Blow Up” and a figure from Picasso’s post-cubist line portraits. He is solicitous and charming, gazing intensely as he concentrates on each question; but also present is a tensely wound energy. He does not seem ever to relax, to be able to or want to. Throughout the peripatetic interview, which took place during preparations for Gregor’s first China exhibition at Galerie Perrotin in Hong Kong and an exhibition at Almine Rech Gallery in London, we switch between German and English.

Hong Kong

We are looking at a model of the Perrotin exhibition.

GH: Here is the main entrance, and this is the first piece!

Gregor is holding up a dirty old rubber-wool doormat with Chinese words on it—出入平安 (chu ru ping an). The incorporation of objects and references to Gregor’s daily life is one of the markers of his practice.

GH: It is a found object: it was in my Berlin flat when we moved there four years ago. I have a Chinese friend in Berlin, from Singapore, who was visiting me and he said, “It’s so crazy to have this ugly doormat and it means ‘come in and leave in peace”. I think it creates a good spirit to go into a flat peacefully, and leaving the flat peaceful, and also a good thing going into a show. And when you go into the show, you are also going a little bit into the home. Two/three years ago I was already thinking, when I get the chance to show in China, then I will show this piece! I also like it because it is colorful, and my art is generally not colorful at all.

All the walls will be covered with videotapes. And the title is “Coming by hazard”—very poetic,. I was with an artist friend, Slater Bradley, in a restaurant when another friend unexpectedly joined us; my English is not so good, so I described this as “Coming by hazard”, and Slater said it would be a great title for a show, because it is very poetic and you have to give a show a title like this. And if I gave a show this title, then he would write the press release.

Then I was sitting in my flat and I was looking at this art piece here, from an old teacher and mentor [an etching by Thomas Gruber—“LE JEU DE L’AMOUR ET DU HASARD”—a homage to French playwright, Pierre de Marivaux’s 1730 renowned romantic comedy, “The Game of Love and Chance” 《愛情與偶 然狂想曲》). In the play, a woman who has been engaged for an arranged marriage awaits a first visit by her betrothed. To get a better look at him, she swaps places with her maid but, unbeknown to her, he has also swapped places with is valet. For the invitation, I photographed the reflection of this etching in one of my mirror paintings, which I sometimes make.

We have left the main room and are walking through the studio to another room.

So here is the top and you can see the reflection.

The mirror works are composed of video and audio tape applied to a surface, which is reflective due to its metal-acetate composition. Video tape itself is made by “painting” metallic particles onto a base. They are black in appearance, the color of the tape.

We hold the image here [opposite the mirror] and take the photograph. Then we turn it [the image, around] using Photoshop, so that you can see it in the right way. For me it was important to show my mentor’s work reflecting in a work of mine. So that was a kind of homage to him. The work of the teacher is reflected in the work of the student.

CM: What are these numbers?

GH: That is the starting point of the videotape, the VHS. The tape is recorded with a song from Jacques Brel [Belgian singer, songwriter and actor, 1929-1978, from his 1968 album L’Homme de la Mancha—Man of la Mancha].

CM: So it matters what the recording on the tapes is; it’s not random: you choose particular songs, particular movies to go with the painting.

GH: Yes, and the VHS is empty, so you can fill it by yourself. I will make a portrait of you now—you have to get close up [to the surface].

…so, here it is! I will send it to you.

CM: It’s amazing—the black vanishes!

We return to the exhibition mockup in the main room.

GH: There is also the image in the show. And there are other things from my flat. The patterns [on a black-and-white painting] come from this handbag—this one. And if you look in the corner of the invitation card—I didn’t see it, my sister noticed it—here it is again. And the patterns on this painting come from a tray. And this one is from one of Alicja’s shirts [artist Alicja Kwade]—a quote from, Einsturtzende Neubauten’s “Susej”: laß uns nach Hausegehen (Lets Go Home) /… “sag den Sternenzauber ab” (Cancel the Star Magic) on their 2007 Album “Alles Wieder Offen”—Everything Open Again. The lead singer, Blixa Bargeld, looks a little like Gregor too]

CM: So it’s a huge self-portrait, really.

GH: Kind of. Everything is connected to this flat. This is the starting-point—this house.

CM: Well it is a self-portrait in the sense that it is showing you in your circumstances, in your home. It is very personal—it is your home, so it becomes a self-portrait.

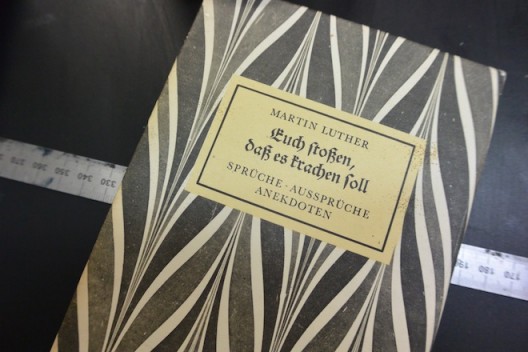

GH: I think it is also the idea that something exists, like here [a door], and when you go into our apartment, the kitchen is on the left side; so the idea is to maybe hang it on the left-side [of the exhibition relative to the entrance]. And that piece [another work] is intended to hang on the left of the entrance. And that comes from this book—Euch stoßen, daß es krachen soll! It is very sexual— Push You So It Bangs!

I am laughing out loud—it is a 1983 compilation of sayings and quotes of protestant bible-translator Martin Luther. A less exotic translation might be “Clink drinking horns together, till they break!”

So [because the book is a] translation of Martin Luther. So I was thinking I had to do something to do with me and with the title. And the audiotapes [that comprise the image] also relate to Luther because they are recorded with Gregorian Chants [and are also a play on Gregor’s name].

And that one there [says Gregor, pointing to an artwork in the model] that will be something super special. It is new. Maybe I can show you what we are planning.

Die hirnhölzerne Pforte

Now we are walking through the building, up echoing stairs to some additional rented office rooms taken to prepare the exhibition.

GH: Here is something we are still working on. I am very proud of it and I want to show it to you.

We are looking at a framed-board covered upon which ‘slices’ of audiotape-wheels are arranged in a parquet fashion. The surface is a highly reflective black color.

GH: That is “die hirnhölzerne Pforte” (“The End-Grain Portal”). We have to close the holes [from the tape spindles].

CM: Why?

GH: So there is no wood behind it [so the surface is consistent – like a parquet floor].

Arranging tape-slices within the frame, Gregor revealed a striking effect of the work, whereby the videotape becomes its own parquetry dance floor.

GH: The idea was first to glue [tape disc slices] directly to the canvas, but it was too fragile, so we first glue them to a base.

CM: It looks amazing.

GH: Initially I wanted to make a whole floor, like with “Hirnholz” parquet.

CM: —“Hirnholz”?

GH: “Grain cut”—the end grain or cross-cut of a piece of timber. It’s the hardest parquet.

CM: So ideal for dancing. And that plays to the theme of music. What sort of music?

GH: Oh, very different. It is symbolic for everything possible and everything possible is there—for instance a lot of Turkish music!

CM: Also great for dancing!

GH: Absolutely! When it hangs in the exhibition, I think it will work really well. There is also the record [another work, a large round of recording tape].

Tape Collection

Church bells chime outside. We are looking at a montage image composed of hundreds of cassette tape covers with customized photographic-print inner-sleeves.

CM: So it’s a portrait of two people? You?

GH: —and Alicja.

CM: And the tapes are a collection of your favorite music?

GH: No, everything possible. But she took the photo—a selfie—I was tired and laid my head on her lap. She sent me the photo and I thought, what is that then? In the exhibition in London, there is also something of our home too.

German Retropop

We return downstairs to the exhibition model. We are looking at large ‘abstract’ works.

GH: All these tapes I have collected since the beginning of my art studies, when I was 20, 22. There are a couple of “holy” things included but it is not important what. And they rain down [the canvas] and here are the marks where each song ends. The picture is actually a cut-out of a the bigger work that stands there in the reverse version.

And here is this black-rain but it is nonetheless a white picture. The surface is first sprayed with acid-free adhesive, then it is masked it with fixative and then covered with videotape. Wherever there was fixative, the tape doesn’t stick. Then the tape is peeled off and wherever the surface wasn’t masked, the particles from the surface of the videotape remain.

CM: So this is the positive-negative.

GH: Yes, so now we have the positive.

I point to some expressionistic marks.

CM: And what is the meaning of these gestures?

GH: It is also an accident, while with the spray I don’t know exactly where it lands, because I cannot really see what it will look like. I have an idea, of course, more or less, but with the finer fixative, it is really uncontrollable.

Walking down Brenton Road

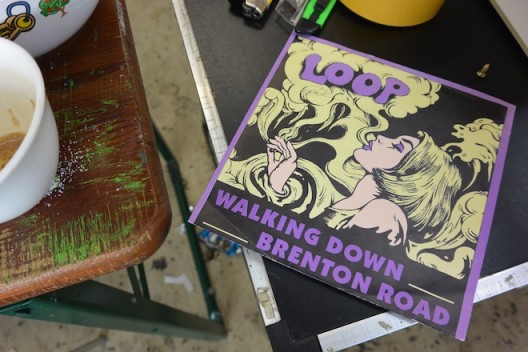

GH: This is for the art fair in Hong Kong, for Wentrup.

It was the cover for the high-school band where I used to go to school. The band doesn’t exist anymore—it was called “Walking down Brenton Road” and the Single, “Loop”, has a drawing from Torsten Kärchan. He could always draw so well, somehow it looked like Roy Lichtenstein. He did it in the 9th grade. I heard that he died a couple of years ago. He must have been my age. And that was a T-shirt, and that was the single LP. I borrowed it from a girlfriend back then—Shila Khatami. She has an exhibition at Autocenter [a Berlin artist-run art space] right now. I will play it for you now.

As a London-punk sound fills the room, Gregor explains the multi-stage process for transferring the image.

GH: …then a third format comes on top, and once again the tape is laid on top, so that it looks the same as the T-shirt.

CM: The same texture.

GH: Yes, like Lichtenstein and Polke—German Pop Art! Retro-pop – German Retro-pop! I used to think I make “Baroque Minimalism”, but now it’s “German Retro-pop”.

Tape Space. A short note on Gregor Hildebrandt

Weeks later in Hong Kong, I went to the opening of the exhibition at Perrotin. The walls were covered in Gregor’s signature videotape. The effect was crystalline and obscure: a mausoleum, a luxury Hong Kong boutique, even—a time capsule for space and a space-time capsule, with works in suspended animation, waiting to be revived in a distant galaxy. And again I thought of the party in “Blow Up”, and its weird alienation of the subject (“I thought you were supposed to be in Paris”, “I am in Paris”). Afterwards I thought the ideal way to see Gregor’s work could only be in the studio, surrounded by and part of the seeming chaos of creation and production, and I felt privileged to have experienced it. By comparison, this “other” space created inside a Hong Kong high-rise seemed asthmatically perfect: it was impossible to exhale.

On the flight home, I watched “Interstellar”. What fascinated me was not the semi-respectable pseudo-science, but how it played as a metaphor for film itself; as a time machine that could project us into other possible worlds via two-dimensional film stock and one-dimensional data. Matthew McConaughey’s character is able to see his daughter across the space-time continuum, seemingly close enough to touch, and he screams to be heard in her realm of space—earth—yet is barely able to make his presence felt, bar the shudder of the minute-hand of the watch he gave her. And I thought about Gregor’s exhibition and reflected that the visitors were similarly caught—Alice-like—inside the liminal space of the videotape curtain, inside a time machine that could transport us to other worlds—to a flat in Berlin with an artist couple, or a school punk band, or a 16th Century radical cleric—beyond a black event horizon that reveals itself as a white mirror of our existence.

Interview conducted Thursday, 12 February, 2015, at the artist’s studio in Berlin.

Gregor Hilderbrandt “Coming by Hazard”

Galerie Perrotin (50 Connaught Road Central, 17th Floor, Hong Kong) Mar 12 – Apr 30, 2015

Gregor Hilderbrandt “In Weissen Sträussen liess den Duft der Sterne Schneien“

Almine Rech Gallery (11 Savile Row, 1st Floor, London) Mar 4 – Apr 11, 2015