By now, the stink in one corner of the basement is very strong—made worse by the adjacent fan installation (Liao Fei’s “About Matter No.1”) wafting it around. The culprit is Chen Qiulin, whose work “The Hundred Surnames in Tofu” spells out Chinese names in stinky tofu; or, one might blame the curator of the Chinese “Platform” exhibition, Huang Du. Some might instead hold Chen’s gallery A Thousand Plateaus Art Space responsible, as the inclusion of this work might have been less the curator’s choice than theirs. Or was it the art fair that drove the content of all the Platforms?

Borrowing from the Art Basel model, Art Stage Singapore has this year sought to emphasize content, and to integrate it closely with the sales imperative of the fair. Practically, this mainly meant a decision to have eight regional or national “Platforms” positioned among the booths. These Platforms are conceived as “sales exhibitions”—for some, this is something of an oxymoron. They should not be taken as the completely pure selections of the curators; where there is an interest in sales and where each work is provided by a gallery, these choices become slightly different—one might tactfully say “shared”. It was remarked by a couple of the curators involved that in fact, a number of the art works had been chosen already. As guests, we can make predictions as to which those were.

But this is an art fair, after all, not a museum (those too are compromised in many similar ways). Such is the relationship between creation, commerce and display now that concerns about the dynamics of these Platform exhibitions at Art Stage shouldn’t be singled out. Rather than focusing on how exactly these works got here, one could choose simply to look at their presentation and content.

In no particular order, the Platforms are: Australia (curated by Aaron Seto), Central Asia (by Charles Merewether, formerly of the ICA at Lasalle College of the Arts), China (by the noted curator Huang Du), India (by Bose Krishnamachari, Artistic Director and co-curator at the first Indian Biennale), Japan (by Mami Kataoka of Mori Art Museum), Korea (by Kim Sung Won, curator, critic and educator), Taiwan (by Rudy Tseng, curator and collector), and Southeast Asia (done by the fair and a handful of regional advisors). The Platforms are arranged around the fair map. The largest, South-East Asia, is at the back of the hall; the others run down the sides, among the booths. Some, like Japan, are well-insulated from the fair, providing an immersive experience; others, for example China and India, are more open to the flow of visitors. Each has its own wall text with names and an explanation, and the fair’s organizers imagined them all as being different in feel from the booths.

Was this a successful exercise? In general, the response to this idea has been overwhelmingly positive. Some question the focus on geography, and others want to ask again “What is Asia?”; for galleries, it was at times awkward to have a booth positioned next to the high, blank outside walls of a Platform. These and the aforementioned reservations about the selection process, however, seem to have been the only criticisms. Whereas a massive Indonesian zone last year sucked attention away from the booths and made some more local galleries feel neglected, this year the spread has been broader and more inclusive. The decision to pool South-East Asian works together seems to have gone down well—though admittedly this was still a dense and extensive area to have to deal with. Through the other Platforms, this observer was among those who appreciated instances of focus on particular points of origin. With so much to digest across the fair as a whole, the use of flags or regions here to signpost groups of works was less a hindrance than help. Though one might not have fully grasped each curatorial theme, the Platforms did provide a moment of pause amid the open flow of gallery booths, giving a chance to contemplate the work and its content with a little less haste (and scrutiny from the staff).

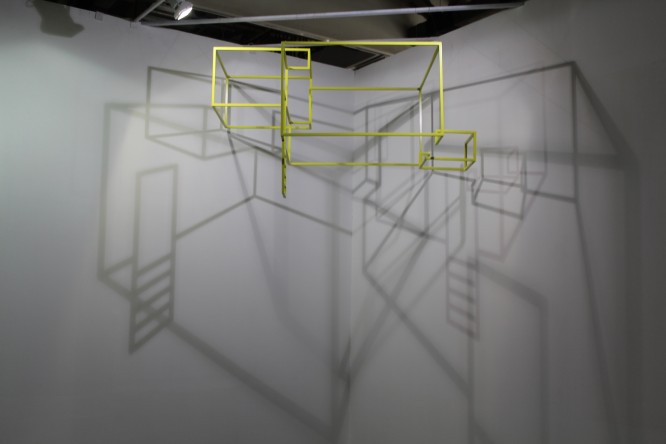

Particular works stand out. In the Australia Platform, the kaleidoscopic video work “Syria” by Khaled Sabsabi, very well-presented in a clear, walled-in space, was both visually captivating and pertinent. On an outward-facing wall, the porcelain and mixed-media pieces by Juz Kitson (“Changing Skin”), were also memorable, if not to everyone’s taste. In the Indian Platform, the carved stone and feather sculpture “Strange Beginnings I” by Sakshi Gupta is a striking, textural piece. Well-suited to such a full fair environment was perhaps Nobuhiro Nakanishi’s work “Layer Drawing—the Tactual Sky,” a composite cloud image across multiple translucent sheets suspended from the ceiling which snaked through the room with finesse, representing Japan. In the extensive South-East Asian area, artists from Myanmar and the Philippines left good impressions, among them Wa Nu and Tun Win Aung (working together), and Mike Adrao, respectively. Although an all-video display was perhaps not the wisest choice for a fair (where one’s attention is stretched, at best), the Central Asian Platform contained contemplative pieces offering perspectives from a region seldom seen from outside through the lens of contemporary art. Movement came too from the Taiwan Platform, where small kinetic and lenticular works by Kao Chung-Li drew one in with Dada-esque appeal. More sedate but with the high quality of production one has come to expect from Korean art, the photographic piece “Utopia #032” by Seung-Woo Back occupied a wall in the Korean display with confidence.

One could go on picking out observations from this group of exhibitions. In short, the Platforms at Art Stage offered much to see and consider, and artists’ names to note. They extend the mode of seeing and selling that must be at the heart of the fair, but introduce a slightly different tone and context for it. It is not clear yet if or how this idea will develop in next year’s fair—Director Lorenzo Rudolf seems satisfied, though remains reserved—but one can be fairly certain it won’t be disappearing from the line-up.