by Christopher Moore

Les contes cruels de Paula Rego

Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris

17 October 2018–14 January 2019

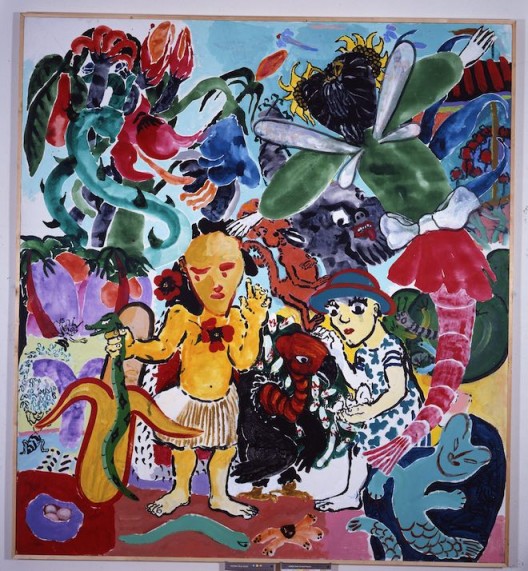

The pictures of stocky women in ballet dresses, engrossed in play, have almost become shorthand for Paula Rego’s pictures. But glance through any book on her and one immediately remarks the extraordinary diversity of her art, whether in style, subject matter or media: abstract and figurative pictures; naïve and realist works, classical and cartoon-like; etchings, acrylic and oil paintings, drawings and pastels (the latter on unusual surfaces like canvas and primed aluminum). There are the experimental graphic pop-works of the 1960s. Her mixed-media collage works from the 1970s, such as “Domestic Scene with Green Dog” (1977) are informed by the visual planes of Surrealism, whether of Salvador Dalí or Ashile Gorky, and her lithographic posters, reveal Rego as an equally-talented abstract as figurative artist. This was followed by a period of naïve expressionist figuration in the 1980s, often using layers of acrylic paint, sometimes watered down to appear like ink (“Paradise,” 1985). In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Rego worked on etchings, with a talent rivalling Lucien Freud, revealing her fascination with nursery rhymes and children’s novels–Three Blind Mice” and “Jack and Jill Went up the Hill” and Peter Pan. Then came people the anachronistic costumes, often 19th Century dresses recalling Impressionism–and the strange pictures of people with giant misshapen dolls and puppets. One of the most important series of Rego’s career is her “social-realist” portraits which gazed unflinchingly at women’s experience of abortions.

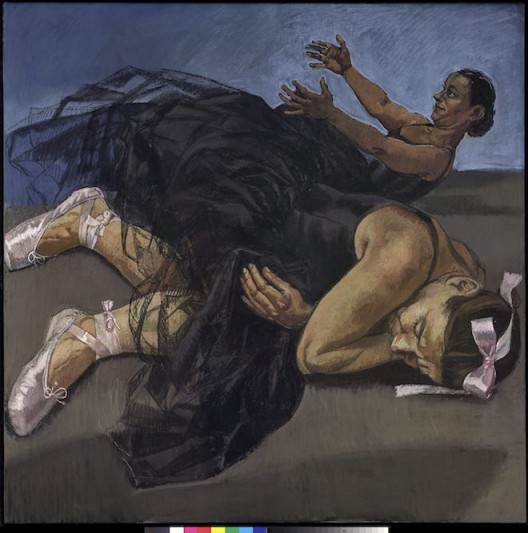

宝拉·雷戈,“白雪公主吞下毒苹果”,1995,木板上色粉,170 x 150cm.

In the mid-1980s, two themes emerged in her work which became recurring leitmotifs: the child-woman figure and animism. In “Snare” (1987) we see a child-woman wrestling with a dog next to a nondescript wall. She has him–definitely a him–on his back, his front paws in her hands and his tail between his legs. On the floor in the foreground are a (real?) toy horse-and-cart, an upturned crab and, to emphasize the sexual tension, a small spray of roses. There is also a flower nestled in her braided hair. These child-women are not mere ciphers for herself but narrative memes and characters drawn from history and art history, but which refocus it from a woman’s critical perspective.

This is important. It is too easy to reel off a list of influences, like Goya, Degas, Gauguin, Lautrec, Picasso, and de Chirico. It frames Rego within a derivative context and a masculine one at that. A great artist uses the work of others like any other medium, whether oil, ink or pastel. Though it is questionable that Picasso ever said, “Good artists copy, great artists steal”, let’s take these words, because they could easily apply to Rego. She uses art and literature, high and low, with paint and pastel, to tell stories, fables, fairy tales, each with a visceral heartbeat.

宝拉·雷戈,“无题”,1999,蚀刻,19.6 x 29.2 cm

The scenes are deliberately theatrical but unlike in fables and fairy tales, there is often neither beginning nor end. We intrude upon a scene at a crucial moment, ignorant or only half-informed of context. The motivations of the actors remain to greater or lesser degrees ambiguous, indeed it is this that often makes them so menacing. In “The Soldier’s Daughter” (1987), a dead goose lies in the lap of a woman, his neck hanging between her splayed legs. Is Leda going to pluck Zeus? The woman is dressed as a peasant, but she wears lipstick and a flower in her hair; there is something oddly seductive about her violence, much as in Artemesia Gentileschi’s “Judith Beheading Holofernes” (1611-12). In the bottom corner, the minuscule toy father-figure, in soldier fatigues walks away, while a grey mother-figure kneels praying in the other, gazing after her absent/errant husband.

Portrait of a Lady

Paula Rego was born in 1935 into a bourgeois family in Lisbon and grew up there during the fascist Salazar dictatorship – a time marked by the pervasive, conservative influence of the Catholic church. Even from an early age, she loved making pictures. In 1952, aged 17, Paula was sent away from Lisbon to London, initially to attend a finishing school for young ladies. Unhappy there, Rego managed to convince her parents to allow her to study at the Slade School of Art (1952-1956). For a young woman from middle-class Portugal, the culture shock was stark – at once liberating and daunting. It was the beginning of the sexual revolution in the West, which inevitably benefitted men more than women. Though still illegal, abortions were common. As artist Colin Wiggins observes:

“With hindsight, this period provided her with an opportunity to observe first hand the world of love and lust, loyalty and betrayal, of burgeoning relationships that could be happy and fulfilling, or abusive and controlling. Rego was not just an observer of this world, she was an active participant.” (Wiggins, p. 5)

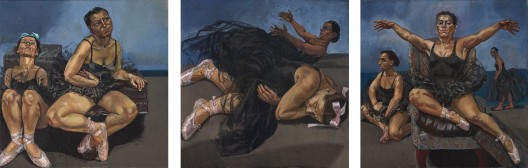

宝拉·雷戈,“迪士尼幻想曲之跳舞的鸵鸟”,1995,三联纸上色粉镶铝框,每幅150 x 150 cm,伦敦萨奇收藏

Rego fell in love with one of her fellow students, Victor Willing. From 1957 the pair lived in the fishing town of Ericeira, on the coast of Portugal. Following Victor’s divorce from his first wife, Paula and Victor married in 1959. They had three children: two girls and a boy. Their marriage was at times difficult. Victor had his lovers, and eventually, Rego took her own too, which inevitably informed her art. They split their time between Portugal and London, where her father had bought them a home in Camden Town. The death of Paula’s father in 1966, necessitated that Victor take over the business, although he had been recently diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis. During the 1974 revolution, the business failed when the factory was taken over by revolutionary forces, though Paula and her family had supported the leftists. The family moved permanently to London, where they lived until Victor’s death in 1988. The same year Rego had her first retrospective show, at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon and the Serpentine in London. I asked Paula if 1988 was a key turning point in her career:

“1988 was definitely a turning point. My approach didn’t really change; it just went on. I had more confidence though, of course, which I think must have affected what I did in some way, or how I did it.”

In 1962 Rego had begun exhibiting with the influential London Group, whose members included David Hockney (b.1937) and Frank Auerbach (b.1931), and she continued to exhibit regularly thereafter. But it was the Serpentine show that secured her position as one of the leading figurative artists of her generation. With critical acknowledgment and released from responsibilities, Rego could make art with the freedom of a woman who has had to measure the value and weight of liberty for a very long time, both hers and others. One work from this period bares particular examination. “The Family” (1988) depicts a man in a suit, perched on the edge of a bed, being dressed by a woman and a girl. His face is obscured by the woman’s upper arm as she helps him with his sleeve. The girl stands between his splayed legs. Apparently, he is too ill to dress himself: or perhaps he is already dead. The posture of the girl is weirdly Balthus-like in its sense of sexual suggestiveness, or threat. Another girl stands in front of an open window, hands clasped and smiling, casting a shadow in front of an antique wardrobe. Maybe she is praying, because the cupboard’s upper part looks like a miniature oratory, decorated with a picture of the Madonna above Saint George killing the dragon; the lower part of the wardrobe is secular, with a monochrome picture of a stork, ambiguously either feeding or killing a fox. The setting recalls Velázquez’s “Las Meninas” (1656).

Awkward Models and Strange Dolls–Ventriloquism

People, particularly women, do strange things in Rego’s pictures. The battle between elegant desires and grotesque realities frequently haunts her work. Sometimes the women have a childlike awkwardness, or the children are disturbingly wise. Sometimes women are animals. In Rego’s “Dog Women” pastels series from the mid-1990s, we see them singing (“Baying”, 1994), licking themselves (“Grooming”, 1994), even lifting their leg to urinate against a bed (“Bad Dog”, 1994). The eponymous work from the series recalls Goya’s “Saturn Devouring His Son” from 1819-23. The dog-woman crouches on the floor, head low, wild-eyed and roaring, her skirts hitched up above her naked legs: is she menacing because she is cornered, or is she giving birth? The ambiguity is painfully acute. In the Ostriches series, women in black ballet tutus stretch and roll about on leather cushions unseated from sofas. Skirts are pulled up overheads and cover mouths. Their ages are indeterminate, but these are not young women. They are strong, experienced, jaded, proud and cackling. In all these works there is the sense of the pathetic aspiration to be part of society, of fear of humiliation, and at the same time, a latent desire to rebel, to be shameless, and to bite! Sometimes though they are victims. Later we see Disney’s Snow White not dramatically threatened or charmingly triumphant but sprawled on the floor, middle-aged and disheveled – raped, really (Snow White Swallows the Poisoned Apple, 1995)–older, abused, and no longer ‘snow white’. The awkwardness becomes viscerally painful in Rego’s series of pastels and etchings, “Untitled”, which explored the isolation, humiliation, and horror of abortions, from a woman’s perspective. They are too cold to be accusatory: rather, they hold us accountable.

宝拉·雷戈,“迪士尼幻想曲之跳舞的鸵鸟”,1995,三联纸上色粉镶铝框,每幅150 x 150 cm,伦敦萨奇收藏

In “Speculum of the Other Woman”, the French philosopher Luce Irigaray (b.1930) famously uses the philosophical styles and structural methods of philosophers from Plato to Freud to critique them. Her strategy itself is knowingly adopted from Chapter 14 of Ulysses, in which Joyce mimics works from the history of English literature, from Geoffrey Chaucer to Jonathan Swift, as a device to reflect the 9-month gestation of a baby in the womb. A key critique of Irigaray’s was the inability of male literature to account for female perspectives, even while it professed to speak for them: an unaccountable and unaccounted (female) coefficient was always missing. Irigaray’s literary ventriloquism articulates this critique. Rego’s referencing of art history operates similarly. It is not a mere quotation for the sake of marking historical lineage. Nor does it involve the knowing appropriation and romance of post-modernism, for it neither ridicules nor mourns stylistic forebears. Her critique comes through the narratives of her painting and drawing.

If we look at Degas’s pastel paintings of dancers or say, for instance, at Toulouse-Lautrec’s paintings of nude and semi-nude women, such as the small “Rousse dit aussi La Toilette” (1896), romanticism is always present. These fantastical characters are trapped in a male artist’s dream. The softened pastel marks of Degas particularly encourage this atmosphere of reverie, whether the subject is a prima ballerina or the exhausted dancer in “L’Attente” (Waiting) (1882). Rego’s “Ostriches” however are just themselves, a group of women who haven’t forgotten a child’s wonder at Disney’s Fantasia – the Oscar-winning 1940 animated film. These women in their black tutus are not on a stage, they are not performing for an audience, but themselves, both ignoring and embodying the parodic natures of Disney’s own performing cartoon birds. The use of pastel here is key. Naturally a softly dusty material, pastels are used by Rego because of the immediacy of the medium in the hand and its dual nature as both a material for line (drawing) and pigment (painting):

宝拉·雷戈,“迪士尼幻想曲之跳舞的鸵鸟”,1995,三联纸上色粉镶铝框,每幅150 x 150 cm,伦敦萨奇收藏

“The difference is that the way I do pastel is like drawing, in color. It’s just lines and lines and lines. Using pastel is more, like, ‘thrusting’ – I don’t know how else to explain it.”

Areas of pastel color also bare an ambiguous visual depth because they tend to absorb rather than reflect light, in contrast to the way a glossy oil-painting sometimes does. She does not smudge or soften the lines and color planes as Degas was want to do. The dancers are built like sculptures out of pigment, but with none of the seductive though superficial sheen of either oil paint or marble stone, and this reflects the subject matter. These women fantasize but are not fantasies. They are corporeal, strong characters, a touch absurd but not weak. They are uninhibited by the male gaze, which would undoubtedly infantilize them, dressing them up as dolls.

In recent years have, Rego has designed and made giant dolls of her own to act as models, alone and with live models. These lumpen rag-doll characters often with shockingly misshapen faces are at once helpless and horrifying. I asked Rego if they were simply dolls or artworks in themselves, and she answered emphatically:

They’re not meant as artworks. They’re like people. They are people! I can make them as grotesque as I like though, which can influence the characters in a scene.

In Rego’s pictures, they immediately become the static center of attention, the strange demigods about which people dance and attend. They hark back to her Surrealist inspirations but truly, they are not the stuff of dreams but players in Rego’s stories, because ultimately, Rego is a story-teller of tales with enigmatic endings, not parables and nothing quite comforting but possessed of a bewitching and unaccountable otherness. The gods and heroes are gone. It is Circe’s tale of the Odyssey.

Bibliography

Articles

Ben Eastham and Helen Graham, “Interview with Paula Rego”, The White Review, London: January 2011.

http://www.thewhitereview.org/feature/interview-with-paula-rego/

accessed 22.08.2018, 10:04.

Sandra Miller “Fashioning Subversion. Clothes and Their Meaning in Paula Rego’s Paintings”, Apollo, January 2006, pp.20-27.

Paula Rego, “Paula Rego: Germain Greer Scared Me and the President of Portugal Nearly Killed Me”, The Guardian, 20 February 2018

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/feb/20/paula-rego-painting-all-too-human-tate-britain-germaine-greer

accessed 22.08.2018, 10:13.

Colin Wiggins, Paula Rego. The Boy Who Loved the Sea and Other Stories, Ex. Cat., Jerwood Gallery, 21 October 2017 – 7 January 2018, Hastings Old Town, East Sussex, 2017.

Exhibition Catalogues

Paula Rego, Ex. Cat., Museu Serralves, 15 October 2004 – 23 January 2005

Paula Rego. The Boy Who Loved the Sea and Other Stories, Ex. Cat., Jerwood Gallery, 21 October 2017 – 7 January 2018, Hastings Old Town, East Sussex, 2017, curated by Colin Wiggins.

Monographs

John McEwan, Paula Rego, 3rd edition, Phaidon: London, 1992 (2006)