This piece is included in Ran Dian’s print magazine, issue 3 (Spring 2016)

For the rare few who have braved reading it, Gertrude Stein’s 1925 novel The Making of Americans posits a kind of endlessness, an infinitude, in its stacks of paragraphs comprised of long, winding, repetitive sentences made up of short, simple words. Its singsong rhythm puts the reader into a sort of trance. A similar trance-poetics is evident in the films of James Benning, who, as Stein did in literature, achieves a temporalization of space and a spatialization of time. Often misread as a structuralist filmmaker, Benning is really more of a landscape poet. His work reflects a complete surrender to the mired totality of the natural world and yet is ever mindful of humanity’s tinkerings and contaminations. Like Stein, Benning discovers in the American landscape rich deposits of meaning in both its beauty and instances of ugliness. With its inferences of boundlessness, it serves as the primal locale for the poet’s vehicular wanderings: fertile soil for the implantation of the impossible dream of freedom, of divorce from the strictures of the supernal and the unpleasantness of history, of a Real all the more remarkable for being spread right before us, blinding us with its encoded morality tale of everlasting life.

The landscape, like all objects big or small, contains an inner life that we come to appreciate only through knowing it. Yet acquiring this knowledge is an impossible task, made all the more vital because of its inherent impossibility. The only way we might come close to it is by going there, treading upon it and across it, diffusing ourselves in its spread. (We understand that we can never completely go inside it, become one with the soil and the fields and the horizon, at least not without severing ourselves permanently from the agency that animates us as living, perceiving beings.) This, we might fathom, is one of the underlying intentions behind “Looking and Listening,” the course Benning taught for thirty years at Southern California’s CalArts. The premise was simple: that these two isolated senses, when combined, yield at least the wondrous possibility of dissolving the chasm between self and object.

In the course, according to Benning, “I’d take ten or twelve students some place (an oil field in the Central Valley, the homeless area near downtown Los Angeles, a kilometer-long hand-dug tunnel in the Mojave foothills, etc.) where they would head out on their own and practice paying attention. I never required a paper, or a work of art, or led a discussion. If there was an assignment, it was to become better observers. And that they did: afterwards their art grew in a far more subtle direction.”1 The only rule was that they were not allowed to talk when in the field, so that they would to pour all their energies into the task at hand. Nor were they allowed to bring with them any recording devices—even pen and paper.

Given the hyper-mediation of nearly every aspect of 21st century life in the “developed” world, and the resultant diminishment of attention spans, the mere exercise of our raw senses seems almost radical: a veritable “total minimal situation,” as the artist and filmmaker Ryan Trecartin would put it. But it is looking and listening that have been at the core of Benning’s filmmaking practice since it began in 1971. Though we typically consider these the tasks of the viewer in the cinematic scenario, Benning challenges this convention, showing us how looking and listening can serve to defy the stasis of passivity: how they can, in fact, serve as vehicles, much like the motorcycle on which the filmmaker has made countless journeys across the American landscape.

And where is the vehicle when it finally arrives?

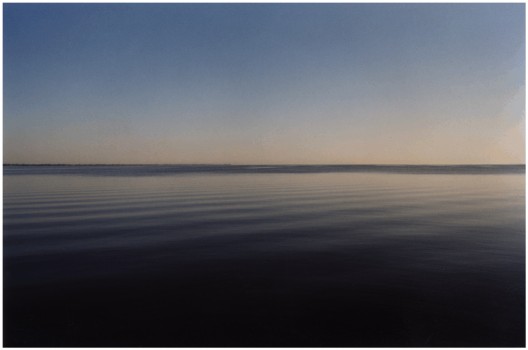

“13 Lakes (2004)” contains static shots, each around ten minutes long, of thirteen different lakes in North America. “Ten Skies” (2004) does the same with skies. “Two Cabins” (2011) is two cabins, each given 15 minutes. It seems so simple—indeed, even boring in its simplicity, as if sitting there, looking and listening, must be some kind of endurance test. In defiance of cinema’s dominant coding, nothing happens. Yet once we get to that place where we are able to really look and listen, this nothing happening turns out to be a lie. Our senses come alive to the subtlety of detail contained within the frame, and the whole it forms. Look at Lower Red Lake, the seventh of the thirteen lakes. We enter in what seems the middle of the day, though we can’t tell what time it is, nor what season; the clouds are too thick. There is but a thin sliver of land, and whatever it turns into is out of sight. The horizon line perfectly bisects the shot, with the sky taking up the entirety of the upper half, the lake the lower. The clouds have grown so heavy that they can’t help but synesthetically drown out the faint lapping sound of the waves, and the placidity of the waters that it indicates. It seems as though the clouds could break at any moment, adding yet more water to our water that is so calm we don’t want any more of it—still, we wait for it to happen.

But in vain. Clouds move slowly, gallantly, from right to left. Suddenly, a light thunder breaks over the scene, a thunder that seems to signify that our time has almost elapsed. The deep, dark blue masks the horizon’s vanishing point: that must be where the planet comes to an end. Don’t steer your ship over there; it’ll fall off! When the earth was flat, the people who came from the other side were aliens. We are aliens ourselves whenever we travel. Birds are chirping but unseen. As our eyes wander towards the bottom of the screen, we see a shore begin to surface, layers of orange underneath. Pregnant soil that will soon give birth—to what? A new species of storm? What will we name the first one? For that is our job, as humans: to name things. Our big accomplishment. The water flowing reminds us of lava. Water moves like clouds: the cloud hills. Water moves faster than the clouds. Nothing stands still. Nature moves fast, like our gaze. This slows it down. Darting between within and without. Stuff happens all the time. You can’t stop it. You can’t control it—and why would you want to? Give yourself over to the movement of non-being—this nature, the joy of its static dances.I had a dream once: the sky. And everything that happened after was but a reminder of this numinous affirmation.

Wandering thoughts: one of the consequences of this type of cinema is that the viewer’s agency becomes part of the final product, which is not the film itself but the experience of watching the film. Whereas narrative cinema based on the Hollywood model attempts to control the viewer’s thoughts and feelings throughout the duration—if your mind wanders, the film has failed, because it has lost your attention, you have grown bored—with Benning’s films, you are allowed and even encouraged to turn inward, melding your agency with the body-mind vehicle that is James Benning. So if, while watching “13 Lakes”, your mind wanders and you think, “I should do the laundry when I get home tonight,” that thought becomes a part of the film’s fabric.2

Even if the time that passes is but a “mere” ten minutes—so much changes. In the first scene of “13 Lakes”, depicting Jackson Lake, the mountains in the background are shrouded in a purple-gray hue. We get to watch as the day dawns. The mountains perform a striptease with the rising light of morning: the darkness slowly moves down their height until the end of the scene, when they stand before us naked, their craggy skin shimmering in the brightness of the day’s sheen.

In Benning’s films, landscape serves as a function of time and all the changes that are impelled thereby. To film “Casting a Glance” (2007), Benning visited the site of Robert Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty” (1970) in Utah’s Great Salt Lake 16 times between May 2005 and January 2007. A landmark of land art, “Spiral Jetty” is vulnerable, shifting its appearance constantly as a result of the climate and the weather, and the rise and fall of the water levels; at times, it is nearly invisible. Its effect upon the viewer changes according to the time of year, the season, and whether one views it from the air or the ground. Very few have seen it, and only the most dedicated have truly experienced it in Benning’s terms. “In order to experience the Jetty,” he says, “one must go often. It is a barometer for both daily and yearly cycles. From morning to night its allusive, shifting appearance (radical or subtle) may be the result of a passing weather system or simply the changing angle of the sun. The water may appear blue, red, purple, green, brown, silver, or gold. The sound may come from a navy jet, passing geese, converging thunderstorms, a few crickets, or be a silence so still you can hear the blood moving through the veins in your ears.”3

In “Casting a Glance” Benning captured this experience, condensed to 80 minutes. Yet even as the film brings us to a place in a more visceral sense than still photographic documentation enables, it simultaneously problematizes cinema’s claim to give us an authentic experience of that place. This built-in critique of the medium—and of presence in a more general sense—is very much part of Benning’s cinema. “I think ‘Casting a Glance’ does it best,”writes Alison Butler. “It tells you that even if you go there you won’t be there, because if you go there again it won’t be like that; it’s constantly changing, and the jetty is this kind of barometer to measure change. That’s true with all places, right? Time is always working and entropy happens; things collapse and are rebuilt. Reality is never static; it’s always moving. What I’m trying to do with films is provide a metaphor for being there, but also the idea that this is just one view, and that many other completely different views exist.”4

For effectively disrupting our normative means of perception when we enter the cinematic scenario, Benning earns the distinction of “bad filmmaker.” It is a title he covets. “I don’t want to make another good film,” he told one interviewer. “There are too many of them … I want to make radical work that adds to a discourse.”5 Benning’s films are radical not merely for their aesthetics, but for their politics as well, in terms of formal matters—specifically the oppositionality of their form—and their encoded references to social, political, and economic subjects. These references might be difficult to perceive, as they are bereft of the sort of Brechtian didacticism one typically associates with overtly political art. For Benning, the landscape is always more than a mere landscape; he refers to it as the scene of a crime. Put another way, his films ask: “What does it mean, in the American context, to withdraw from society, to purposely exclude oneself from the mainstream of discourse?” Not merely to enter a room of one’s own, but to insert oneself in the landscape, cementing one’s isolation from the noisy business of the human sphere by a permanent communion with nature, those very forces that society has aimed to tame and control rather than embrace?

In 2012 Benning released a “remake” of Easy Rider, Dennis Hopper’s 1969 film that is considered a classic of the hippie counterculture. He drove across the United States shooting landscapes from the original locations of Hopper’s movie, devoid of human actors. The landscapes, often mutated or altered by the ravages of time, take center stage, overlaid with selected excerpts of dialogue from the original film. While the remake, as a genre, tends to manifest at least in part as an authorial homage to the original, Benning’s “Easy Rider” is actually highly critical of the lifestyle politics celebrated in Hopper’s classic. In Benning’s view, the “rebels” depicted by Hopper and Peter Fonda are very conventional in their yearnings and desires, revealing a failure of the American counterculture to fully divorce itself from the values of the dominant culture. In attempting to fulfill the neoromantic quest to live on the road, Hopper and Fonda can manage only the most superficial engagements with the locales they pass through and the humans who have put down roots there. Despite their long hair, motorcycles, and rock ’n’ roll, their ultimate desire, expressed at one point in the film, is to retire in Florida and enjoy the good life—perhaps the most conventional of American dreams—with the money they have made in a lucrative drug deal. (On the subject of intoxicants, Benning is fond of repeating Malcolm X’s assertion that drugs are counterrevolutionary.) As Benning observed, the word “Vietnam” is not uttered once in the film—a shocking omission for a counterculture film shot at the height of the war, when protests were tearing the country apart. The protagonists’ interactions with the people they encounter are similarly selfish, superficial, and scornful; the minute the locals satisfy Hopper and Fonda’s needs, they are discarded and forgotten about. One can’t help but be reminded of one of Benning’s earlier road-trip films, “North on Evers” (1992), whose textual narrative, which is Benning’s handwritten diary kept on this particular trip detailing his interactions with the friends, family, and strangers he met along the way, is moving and powerful work.

In returning to sites of Easy Rider’s original filming, Benning observes a contemporary Middle America that lies in ruins. The film is filled with dilapidated storefronts—scenic victims of recession and financial trauma. Main Street USA, we are made to understand, is long dead. Several shots linger on structures built by the Anasazi, a tribe that predated the Pueblo Indians (whereas the protagonists’ engagement with Native America in Hopper’s film is desultory at best). Shot 37 in Benning’s production shows a mansion on a Southern plantation, giving rise to a prolonged meditation on the origins of African America, slavery, and the unhealed racial relations that persist to this day.

The vehicularity of Benning’s effort is premised upon a deep engagement with all of the locales he passes through. He allows himself to become absorbed by the landscape, and part of this absorption is a mindfulness of the historical truths it contains. This is where looking and listening give rise to something greater—a knowing that is a politicization of both consciousness and perception.

Notes

1 Benning in “Draw It with Your Eyes Closed: The Art of the Art Assignment”, Paper Monument, 2012. Excerpted at http://www.papermonument.com/web-only/liam-gillick-and-james-benning/.

2 Benning is quite fond of this laundry example, which he has repeated in several interviews. See for instance Anna Bielak, “James Benning Interview,” Berlinale 2013, February 7, 2013, http://smellslikescreenspirit.com/2013/02/james-benning-interview/.

3 Benning, quoted in Barbara Pichler and Claudia Slanar, James Benning (Vienna: Austrian Film Museum, 2007), 253–54.

4 Alison Butler, “‘You Think You’ve Been There: A Conversation with James Benning about Easy Rider (2012),” Lola Journal (October 2012/January 2013), http://www.lolajournal.com/5/benning.html.

5 Allan MacInnis, Decoding Fear (Cologne: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2015), 198.