by Julie Chun

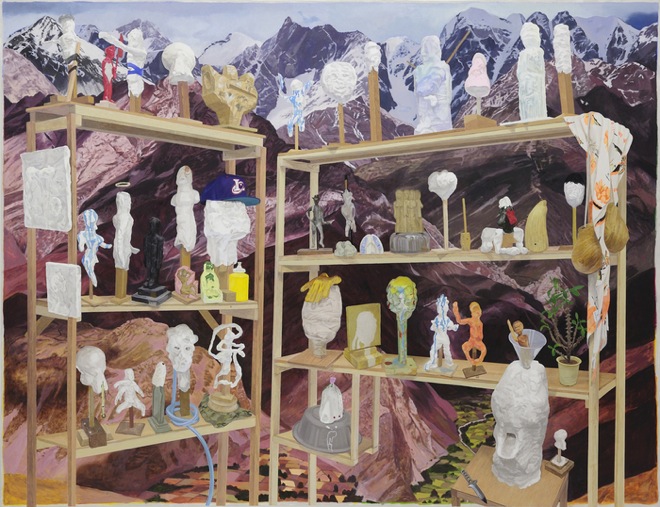

“Unseen Existence: Dialogues with the Environment in Contemporary Art”: group exhibition with Nadim Abbas, Allora and Calzadilla, Ang Song Ming, Araki Nobuyoshi, Masaya Chiba, Jiang Zhi, Maya Kramer, Boris Mikhailov, Yuko Mohri, Sutthirat Supaparinya, Wang Fu-jui, Yao Jui-chung

Guest Curator: Rudy Tseng

Hong Kong Arts Centre (2 Harbour Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong), December 12–January 15, 2015

It was a timely coincidence. The 2014 United Nations Climate Change Conference was in full session in Lima, Peru when the Hong Kong Art Centre flagship exhibition “Unseen Existence: Dialogues with the Environment in Contemporary Art” opened, which seeks to offer new perspectives on ecological change. As the curator Rudy Tseng remarked: “We cannot be complacent with nature’s generous resources. The aim of this exhibition is to address the issue of our connection with our ecology, and to redirect our attention and care to the phenomena of nature that we so often take for granted, which seem to be invisible but are very present.”

As viewers stepped out of the elevator into the dark space of the Pao Galleries, the Thai visual artist Sutthirat Supaparinya opened the vista with a revealing glimpse of the near-sighted decisions humans make without regard for long-term consequences. The large-scale three-channel video “When Need Moves the Earth” (2014) highlights the phenomena of man-made earthquakes. Taking the research of Dr. Christian D. Klose, an American scientist focusing on the causes of natural hazards, Supaparinya documented the seemingly prosaic workings of a Thai coal mine and a water reservoir which generate electricity. Yet these plants build a force more potent than electricity. Their sheer weight produces small tremors that can eventually affect the earth’s plate and natural fault lines thus, triggering severe earthquakes.(1) Mounds of stark black charcoal briquettes were piled up beneath the elevated screens to layer in another dimension to the dystopian vision.

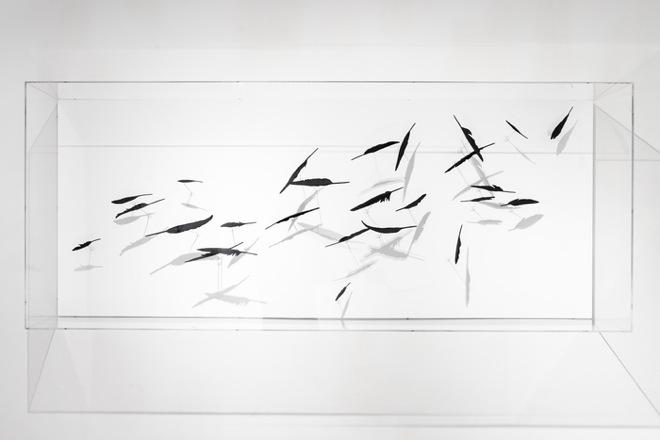

For Maya Kramer, a Shanghai-based American artist, coal is taken as an artistic medium and a topic of discourse. Crushed and pulverized, the toxic carbon was transfigured and recast as lithe branches of a blackened tree that seemed to grow directly from the wall. As the title suggests, “Bound” (2014) consists of unnatural knots twisted into the limbs of the tree, thus alluding to the strange altercations often caused by pollutants to the very fabric of the natural order. Moreover, upon closer inspection, what appears as a flurry of raven’s feathers in “Against the Wind” (2014) is in fact a paradoxical statement about the properties of coal. Pristinely sheathed in a glass box, the delicate feathers appear sheltered from exterior menace; yet each feather has been painstakingly cast from the toxic dust that permeates many Chinese cities. Though loaded with heavy and despondent connotations, Kramer’s meticulously crafted feathers nonetheless, appear to levitate, signifying ascendancy against the forces of the gravitational pull.

蘇圖西亞.蘇芭芭恩雅,《當需求移動地球》,三頻錄像/彩色,泰語對白,英文字幕,片長20分鐘25秒,2014,摄影:Monruadchanan Laphatphakkhanut

馬雅.柯拉瑪,《逆風而行》,煤炭、黏合物、 電線、磁鐵、木頭、有機玻璃,182 x 74.5 x 20 厘米,2014,图片由艺术家提供

The relationship of matter to energy and the search for renewable energy finds a balanced negotiation in the delicate miniature compilations of wind, solar and magnetically powered sculptural assemblages by the Japanese artist Yuko Mohri. She admits her life was profoundly transformed by the tragedies of 2011, when a tsunami from the Great East Japan Earthquake led to the meltdown of three Fukushima Daishi nuclear reactors.Even now, three years later, the full impact of the radioactive toll is still being discovered and re-assessed. “These two events really altered the way I viewed the world,” Mohri explained as she tested the wires, powered by wind, which interact with the aluminum of empty beer cans to light the tiny headlights of miniature cars encased in a once-discarded vitrine cabinet. “Even though the nuclear disaster occurred in Japan, few people…are truly aware of the calamitous affect this consequence has on the world. The disaster has and will continue to alter the lives of those who come in contact with the ocean,” Mohri commented. In her series “Urban Mining” (2014), the wind and sun literally activate her installations, and she adeptly employs her technical proficiency to make visible the utility of repurposed detritus (including bent kitchen utensils and badly stained wooden stool) as objects of contemporary archeology.

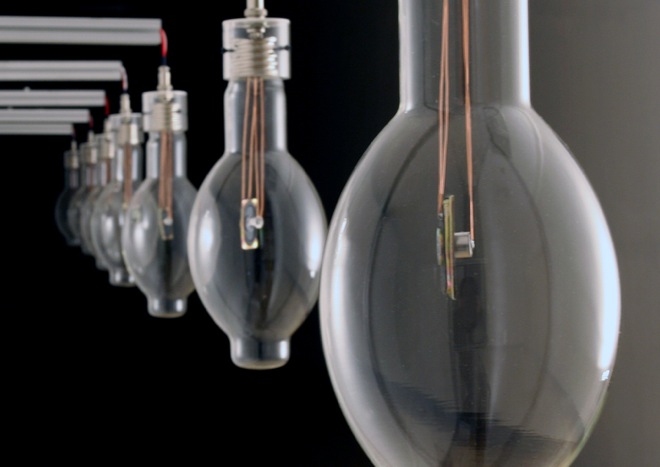

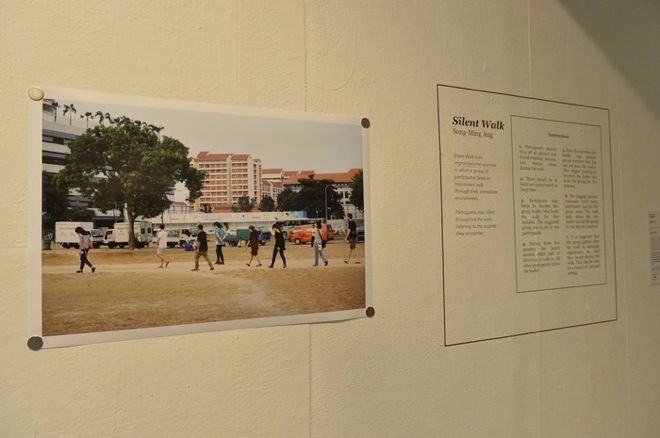

In direct contrast with the monumental spectacles that have dominated recent contemporary art exhibitions in Hong Kong, Taiwan and mainland China, “Unseen Existence” (perhaps in keeping with its subtle title) is subdued yet thought-provoking without sensory overload. Even the prominent sound artist Wang Fu-jui’s “Sound Bulb” (2008-14) emits a low-volume transcendental chime, thereby creating a purified soundscape. Using a miniscule speaker and microphone embedded in each glass bulb, the voices of the audience in the room are processed and played back through SoNo signals (signal and noise in-phase at the ears) to simulate the refracted noise of insects in the natural world that are eclipsed by urban cacophony. Such observation of the oft-neglected aspects of our environment is further elucidated in photographic images of demolished ruins in Taiwan by Yao Jui-Chung; the marginalized members of Japanese society by Boris Mikhailov; the clear blue skies by Nobuyoshi Araki; the pyrotechnic feats displayed on flora by Jiang Zhi; the serene paintings that merge the exterior and the interior world by Masaya Chiba; and in the artist-led “Silent Walk” (2014) by Ang Song Ming.

Yuko Mohri, “Urban Mining- Traffic”, diorama materials, LED lights, used cables, vitrine table, disposed aluminum cans, electric fan, Dimensions variable, 2014, Image courtesy the artist and waitingroom

毛利悠子,《城市礦山—交通》,模型物料,LED 燈、已試用的電線、玻璃櫥桌、廢棄鋁罐、電動風扇,尺寸不定,2014,图片由艺术家和waitingroom提供

王福瑞,《聲泡》,聲音裝置,尺寸不定,2014,图片由艺术家和Project Fulfill Art Space提供

These quiet tributes are sporadically punctuated by Tim Storm’s low-octave elegy to the two elephants that arrived at the Museum of Natural History in Paris in 1789 as spoils of war in Allora & Calzadilla’s “Apatomē” (2013) and the hum of self-roaming rotund vacuum cleaners desperately attempting to sanitize Nadim Abbas’ compact, fabricated Man Cheong Street in the lower level gallery. Entitled “Zone II” (2014), Abbas’ site-specific commission of plastic containers formally replicates hyper-dense residential apartments in Kowloon. Fifty-six of these custom-made plastic “buildings” double as receptacles for construction waste and debris produced during the installation as well as the litter collected throughout the exhibition “Unseen Existence,” thus starkly embodying in visual form the “Junk-Space” of postmodernity’s architecture and its accompanying rubbish.(2)

With the exhibition theme resting on ecological ideals, I could not help but recall the critical statement issued by Jean Aubert and Jean Baudrillard on behalf of the French delegation in their refusal to participate in the “Environment and Design” conference in Aspen, Colorado in 1970. Baudrillard made the criticism that “environmental crusade” was an attempt by wealthy nations to mask the fundamental problem of capitalism and its modes of production.(3) We cannot deny that ideological justifications for fostering a hygienic environment come loaded with social, political, and economic contradictions. Which is why, perhaps, Frederic Jameson and Slavoj Žižek, respectively, alluded that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. Despite what humans do or neglect to do, we are inevitably heading towards that catastrophic direction. Who knows if we can save the world or if Mother Earth even wants our saving? She is, after all, quite resourceful and resilient having survived millennia of physical trauma and stress despite human irresponsibility. Yet, with a bit of foresight and deliberation, we may be able to decrease the effects of our unnatural acceleration. Hence, it is this re-orientation that “Unseen Existence” is tacitly striving for—to make visible the ecological degradation that will ultimately lead to biological disequilibrium for us all.

(1) Christian D. Klose has forwarded the study that the cause of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake was likely triggered by a four-year old reservoir built close to the earth’s fault line. See Sharon LaFraniere, “Possible Link Between Dam and China Quake,” New York Times Asia Pacific, February 5, 2009.

(2) Ren Koolhaas, “Junkspace”, October, Vol. 100, Obsolescence. (Spring, 2002), 175-190.

(3) The French Group (Jean Aubert and Jean Baudrillard), The Environmental Witch-Hunt – Statement by the French Group, 1970.

唐納天,《領域 II》,混合媒體 (真空塑膠模、建築廢棄物、機械吸塵器、膠地板、場壁腳板、建築用漆),尺寸不定,2014,摄影:Roberto Chamorro

Rudy chiba, “1-9225 peaceful village”