Group exhibition at Taikang Space

The most recent exhibition at Taikang Space, “La Chambre Claire,” was a laid back affair that brought together five works capable of being addressed to the idea of “photography.” To have enlisted Barthes’ original title was a pleasant way to frame the show. None of these works are straight photography; instead, in the words of the exhibition text, “This is an exhibition without photographs but the phantom of photography is everywhere to see.

It was the central room here that was the most striking, with Liu Wei’s often-quoted “As Long As I Can See It” series of 2006 (shown that year at Beijing Commune), wherein Polaroid photographs of ordinary objects were presented alongside the objects themselves (a fridge door, a washing machine), which had been brutally sawn off to conform to the photograph’s composition. These works offer a candid play on the relationship between reality and its image as abducted by the lens — where a photograph is widely perceived to be a simple subtraction from reality (remember the verb to “take” a photograph), what if reality were to be re-presented as per that image?

刘窗, 《15号作品》, 混合媒体, 尺寸不一, 2012

Although simple at the outset, these are compelling works whose action generates questions about perception, the integrity of images and the power of the auteur to control and tell of these relationships. Also here was “Work 15#,” a production of this year by Liu Chuang. A plain white structure of a room with a blank doorway cut into it becomes the stage for a gradually expanding and contracting blue light from a facing projector. The vivid, colored area casting soundlessly over an empty form offered an original contemplation on the transmission of light onto a waiting surface (photographic paper, film), as well as a smooth minimalist statement.

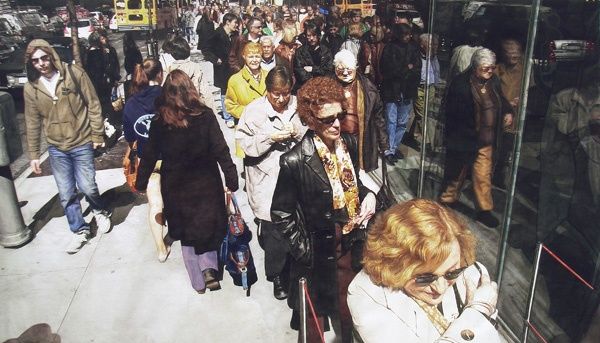

郑国谷, 《MoMA入口排队的人群 2008-2009》, 水墨画, 180 x 300 cm

The rest of the works in the exhibition were somewhat underwhelming in comparison with these two, perhaps lacking the effective combination they share of the visual and physical. Zheng Guogu doubled the inherent illusion of photography, rendering a photograph almost imperceptibly as an ink painting on silk (“The Line In Front of MoMA’s Entrance,” 2008-9); the adjacent installation by Wang Yuyang called “Let There Be Light” (2012) enlists this infamous sentence as a code governing the shutter speed of a camera hidden in a walk-in black box, set off by the entrance of a visitor. Upstairs, Zhang Liaoyuan’s wall of A4 paper packets imply the onset of images on white fields and form an image themselves from the patterns and captions of the packaging. This is an idea that could, like the premise of the exhibition as a whole, have been explained and extended to better effect. As it stood, two strong works were able to speak for themselves, where others — and the wonderful writings of Roland Barthes — did not instill themselves enough.