This review is included in Ran Dian’s print magazine, issue 3 (Spring 2016)

“Juan I-Jong – Japan 1982″ and “Suda Issei – Taipei Kissyo”

Aura Gallery (313, Dunhua N Rd Sec 1, Taipei City, Taiwan), Jan 30–Mar 12, 2016

In the 1980s, photographers Juan I-Jong (阮义忠) and Suda Issei (須田一政), unbeknownst to one another, each traveled to the other’s country in search of fresh photographic subjects. As outsiders visiting another country, they came equipped with a certain lens; searching for certain things whilst overlooking others. Now, over thirty years later, the intertwined visions of Juan’s Japan and Suda’s Taiwan are juxtaposed for the first time at Taipei’s Aura Gallery, in the exhibitions Japan, 1982 (日本,1982) and Taipei Kissyo (台北吉祥).

Both major figures in recent East Asian photography with numerous attendant monographs and international exhibitions to date, Juan and Suda have mostly been considered only within their respective national contexts—Taiwan and Japan. Juan (b.1950), dubbed the Henri Cartier-Bresson of Taiwan, is most often associated with his representations of Taiwanese rural villages, aboriginal communities and urban developments, while Suda (b.1940) is most known for his photographs of Tokyo street scenes and their affinity with older Japanese art forms such as Noh drama. The current exhibition at Aura offers a rare transnational view, and foregrounds the postcolonial, culturally-hybrid context that in fact shaped much of both artists’ work.

Enamored and isolated

Lining the walls of Aura’s lower level is Juan’s Japan 1982, a series of black and white photographs from a 1982 trip during which he visited Tokyo, Ibaraki, Kyoto and Fukuoka. Though it was his first time traveling outside Taiwan, Juan was already deeply familiar with Japan. “When I arrived, it felt as though I already had been there before,” he says in an interview with Ran Dian (all quotes by Juan and Suda have been translated from Chinese by the author), his Mandarin softened by a typical Taiwanese lilt. This was because Juan grew up in the period immediately following Japan’s fifty-year colonial rule, when people in Taiwan still had Japanese nicknames, spoke in a mixture of Japanese and Taiwanese Hokkien, and collected Japanese books and magazines. Juan thus spent his formative years immersed in Japanese culture, watching films starring Toshiro Mifune and Akira Kobayashi, and reading novels by Yasunari Kawabata and Yukio Mishima.

“The light!” Juan exclaims, when asked what first struck him about Japan in 1982. “I had never seen such beautiful light. It was because the air was so clean and clear.” By comparison, Taipei at the time was horribly polluted, Juan recalls. “Every day when we came home to wash our faces, the towel would turn black. The air was always dirty.” Juan also admired the rigorous co-existence of modernity and tradition in Japan, with neither one diluting the other: “they had modernized thoroughly, but also managed to preserve their tradition so well. It wasn’t just Kyoto, but all four places I visited. It was extraordinary.”These aspects of Japan with which Juan was so enamored shine through in his photographs—particularly in those taken outside urban centers: a solemn couple dressed in exquisite Japanese ceremonial wedding garb, a group of tombs in an abandoned field by the sea, a man heading towards a temple half shrouded in mist.

Though beautiful, these scenes are also melancholic and heavy-hearted. “I don’t know if you can tell from the photographs, but I was very lonely throughout that trip,”Juan confesses. In some ways, this loneliness deepened his sense of kinship with Japan, as he saw it reflected back to him in the faces of Japanese people on the street. This was something else that surprised Juan about Japan, as he notes, “the biggest shock, which I can feel even now, is that though Japan was at that time the strongest country in Asia, people there rarely smiled … I could see they lived under enormous pressure; everyone walked around with a grimace.”

Juan captures this collective malaise in scenes of city dwellers: two schoolgirls stand on a railway platform in near identical poses, their gazes averted; one man struggles to push his car across the street while a second one watches impassively; occupants of pay phone booths stand in a row, physically adjacent but mentally miles apart; pedestrians rush past one another with downcast eyes. Several photographs also show human subjects overshadowed by, and at times almost camouflaged with, storefront signs, billboard ads and shop window displays. Together, these scenes reveal the underside of Japan’s 1980s economic boom—the estrangement of human relations, the rigid rationalization of time and space, and the aggressive colonization of human attention by commercial interests.

Nevertheless, even urban alienation isn’t without its beauty in Juan’s Japan. The city dwellers are stylishly dressed; the faces of the two disaffected schoolgirls are bathed in sunlight; the various spaces of the Japanese city are elegantly designed. As Juan’s photographs reflect, Japan was undoubtedly beautiful, but it was an aloof beauty, an untouchable beauty; perhaps a beauty built on present and past inhumanities. When asked about how Japanese people viewed Taiwan in 1982, Juan heaves a sigh, “of course they did not respect us. We were once their colony. To be honest, it’s still the same today.”

One photograph from the series poignantly invokes this not-too-distant colonial past: a single Japanese monk marches down a wide city street waving a Taiwanese flag. According to Juan, the monk wore a sign on his back that called on Japan to thank the Republic of China for not demanding reparations after WWII, as otherwise Japan would not have been able to enjoy its postwar prosperity. “This monk was a news item for a while,” Juan remembers, “they thought he was a strange character because his demands were so unusual in Japan at the time. It was as if this one man was railing against the entire Japanese society.”

Traveling out of homesickness

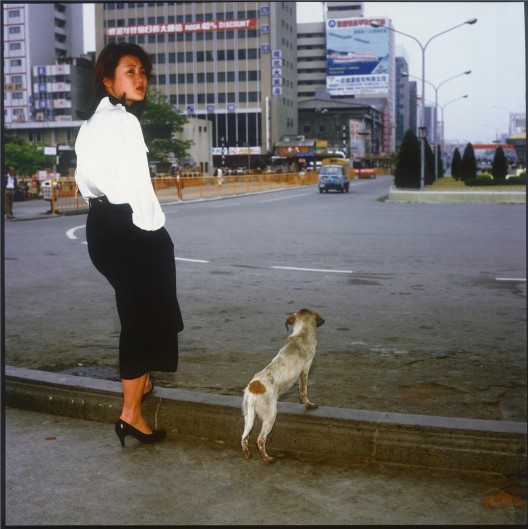

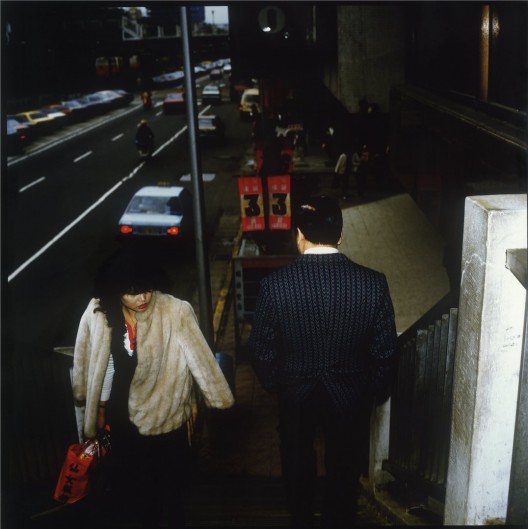

Up Aura’s coiling stairway, a different set of scenes greets the viewer. Suda’s Taipei Kissyo, a series of color photographs taken in Taipei in 1984 and 1990, is exhibited on Aura’s second floor. Here, we find the regimented life of 1980s Japan replaced by the lively disorder of 1980s Taipei. Many of the same subjects appear—stylish urbanites, city streets, phone booths, temples … But these scenes strike a distinctly different tone from that of their Japanese counterparts. Unlike Juan’s Tokyo, Suda’s Taipei feels more like a provincial town than a metropolis. There are more alleyways than roads, more motorbikes than cars, and only a few quaint, gentle ads. The pace of life seems slower, and the relations between human beings freer, warmer, more spontaneous, more intimate.

The contrast here to Juan’s Japan, 1982 is particularly suggestive given what Suda himself admits in his artist statement—he traveled to Taipei in search of an older Japan:

“Having been born in 1940, I was always nourished by Japan’s rapid developments … However, as time passed, vitality gradually disappeared from the streets of Japan. When I began to see the faces of the Japanese people becoming homogenized, I went to Taiwan. When I arrived … my heart beat with an excitement I had almost forgotten I could feel, because in this place, the streets were filled with an air of liveliness, and people’s daily experiences were pervaded by rich sentiments … In retrospect, my obsession with photographing Taiwan perhaps came out of a kind of homesickness.”

After that first visit in 1984, Suda returned to Taiwan almost every year with his camera out of a yearning for the vitality and lyricism he felt had been lost in his homeland.

This vitality and lyricism can be felt throughout Taipei Kissyo, in which we see scenes of young lovers, children, families and strangers interacting affectionately and spontaneously. Vibrant colors add to the general air of liveliness. As we survey the series, our eyes become anchored again and again to brightly colored objects that pop out against muted backgrounds. More often than not, these objects are red—a skirt, a jacket, a balloon, a fan, a flower, a lantern … This string of red gives the series a continuous sense of festivity, as the color red is commonly associated in Chinese culture with good fortune. This is perhaps also a reference to the very title of Suda’s exhibition, Taipei Kissyo (台北吉祥), which literally translates into “Auspicious Taipei.” In addition to festivity, Suda injects a certain playfulness as ordinary scenes are made eccentric by idiosyncratic framing, focus and axial rotation, producing oddly cropped and lopsided faces and bodies, and whimsical juxtapositions of haphazard objects.

In the context of the exhibition title, these lively scenes can perhaps be understood as auspicious signs, which Suda took to foretell a happier outcome to Taiwan’s industrialization than the one at which Japan had arrived. It is interesting to note how his photographs of Taipei differ from those he took of Tokyo—for example, his Fushi Kaden series from the 1970s, which, while equally expressive, are much more unsettling, often haunted by a sense of darkness and repression absent from Taipei Kissyo. Perhaps Suda saw in Taipei a lighter, simpler, more humanized Tokyo.

Appealing though it may be, Suda’s rosy vision of Taipei is a far cry from the polluted, congested, underdeveloped city described by Juan I-Jong. Nevertheless, a second look enables us to locate in Suda’s images the 1980s Taipei of Juan’s memory. Signs of urban squalor and underdevelopment linger in the background of buoyant scenes and creep in around the edges of lyrical moments. This is best exemplified by one photograph in which a pair of ebullient paper fans are posed against the background of a mess of tangled electric wires on a dirty, dilapidated wall. This image perhaps shows most nakedly that which charmed Suda about Taipei—an almost childlike neglect of material development in favor of whimsy and gaiety—its impracticality, its inefficiency, its obsolescence.

“He likes what he doesn’t have,” remarks Juan, who in his own photographic series of 1980s Taipei, Taipei Rumor, shows not the quaint provincial town of Suda’s Taipei Kissyo, but rather a rapidly transforming city and a people under immense pressure to catch up with the rest of the industrialized world. Suggesting that perhaps a city looks different before the eyes of a visitor, Juan speculates of Suda, “Japan once possessed a quality that it later lost, and he found it again in Taiwan.”

This does not discredit Suda’s vision however. As Juan explains in the opening to Taipei Rumor with a quote by W. Eugene Smith: “to portray a city is beyond ending: to begin such an effort is in itself a grave conceit. For though the portrayal may achieve its own measure of truth, it still will be no more than a rumor of the city—no more meaningful, no more permanent.” A photograph can thus only portray a place in the form of rumor, never verify it, never pin it down. Without claiming to represent Japan and Taiwan fully or truthfully, Suda’s Taipei Kissyo and Juan’s Japan, 1982 nevertheless help to document traces of these cities as rumor, and give form to the latent, unofficial, perhaps entirely imagined—but no less real—relations between Taiwan and Japan in the 1980s.