“The Important Thing Is Not The Meat,” solo exhibition by Gu Dexin. Curator: Phil Tinari.

Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (798 Art District, No.4 Jiuxianqiao Road, Chaoyang, Beijing). Mar 24-May 27, 2012.

“The Important Thing is Not the Meat” must be one of the most keenly anticipated Chinese shows of 2012. It is a grand exhibition not only by virtue of looking back over the career of Gu Dexin — very arguably China’s greatest conceptual artist thus far — but also because Gu himself has, to all accounts, quit art. (Though the artist — if we may still call him this — has issued no direct statement on the matter, we can be fairly certain this decision is based on his dislike of the art world in general, and the direction in which he saw it going.) Phil Tinari’s first curatorial occupation of UCCA’s aptly named “Great Hall,” “The Important Thing is Not the Meat” sets the bar for his directorship of the organization, and in being a retrospective, offers a kind of exhibition common amongst crowd-pulling Western Kunsthalles but unusual in China.

Nor is it often one sees a massive solo exhibition executed completely sans the involvement of the artist and actually against his will (what, we may ask, does this say about the exhibition system from which Gu Dexin chose to eject himself?). He once told Tinari he hated retrospective exhibitions because art “has had nothing to do with him” since his final show (at Beijing’s Galleria Continua) in 2009. He disliked the idea of this one, but — having placed himself outside the art-world circus — reserved comment. For Tinari, “It’s pretty clear that this is something we’re doing simply because we believe it’s important, and that this [artistic] position is one that is under-acknowledged in the overall history of how art developed here in the last 30 years.” The exercise of choice is twofold: the exit from art on one side, and the decision (in a mode of institutional responsibility) regardless to show it on the other; Gu’s artistic position we must gauge from the assembled works drawn from nearly thirty years of practice — almost 300 of them in media ranging from paint, plasticine and wood to model cars, animation, Sim-city and monumental sculpture.

顾德新:“重要的不是肉”(2012),展览现场

This shows a portion of Gu’s practice before it ostensibly ceased. There has been some backchat about the real breadth of the show perhaps because many of his most arresting installations have literally — as intended — rotted away; it is an unavoidable, but nonetheless curatorially negotiable fact. For the exhibition “Asiana” at the 46th Venice Biennale, for example, Gu Dexin occupied an opulent palazzo with a myriad of red plastic beads and three glass coffins each containing 100 kilos of fresh beef, the putrefied stench of which forced its removal after just 3 days. Combing through the UCCA exhibition captions, however, one finds only one overt reference to the splendid inductions of decay Gu created over the years, and even then, it’s soft: “decomposition…became a recurring motif… later including gorier substances like pig brains and pig hearts.”

顾德新:“重要的不是肉”(2012),展览现场

At the entrance is printed, phantom-like, the artist’s statement from his first show in 1986, “Gu Dexin’s Works,” at International House in Beijing: “Now my works are here, together with everyone. Each person will understand and experience them in their own way. And that is precisely my hope.” Surrounding Gu’s powerful conceptual legacy is his original and steadfast “No Comment.” As visitors, many of whom have never before seen Gu’s art first hand, we must take what we are given here (such is the nature of retrospectives, especially) and make of it what we will.

顾德新:“重要的不是肉”(2012),展览现场

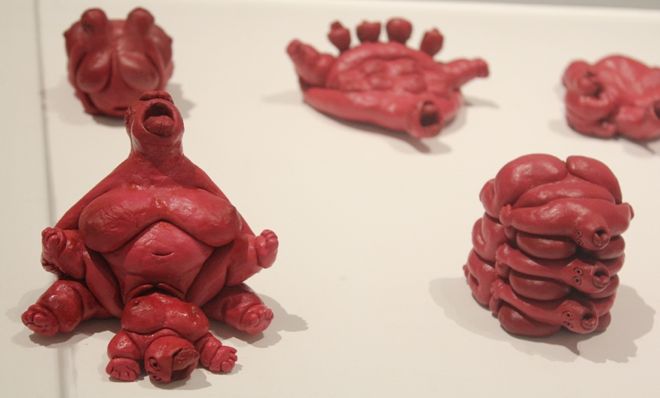

In perhaps the best bit of presentation across the whole show, climbing the wall in an alien column to the ceiling are a collection of Gu’s colored plastic manipulations (1983-85) — things one imagines might scurry away with a squawk when a light is switched on. Grouped together, this flock of polymer fauna take on a strange sense of life, their forms hardened in embryonic mimicry — globules, little spaghetti-like heaps, joke-turds, entrails and brittle stalks. Under the glow of the artist’s blowtorch, obedient plastics are mobilized to rebel against becoming bowls, shoes and utensils: the new-fangled functional items then flooding Chinese homes.

顾德新:“重要的不是肉”(2012),展览现场

Reverting to chronology, the first room snakes through Gu’s early artistic activities: mainly paintings, but also wooden pieces and a series of clay heads of toothed creatures in bright, playful colors. These grin out from a glass case with the blithe ferocity of children’s fiction. On the walls, the paintings, a disparate group of experiments with manners including surrealism, cubism, and abstraction, are an inchoate collection bonded by no uncertain resolve and an evident fearlessness which must later have paved the way for Gu Dexin’s brute-conceptual installations.

顾德新:“重要的不是肉”(2012),展览现场

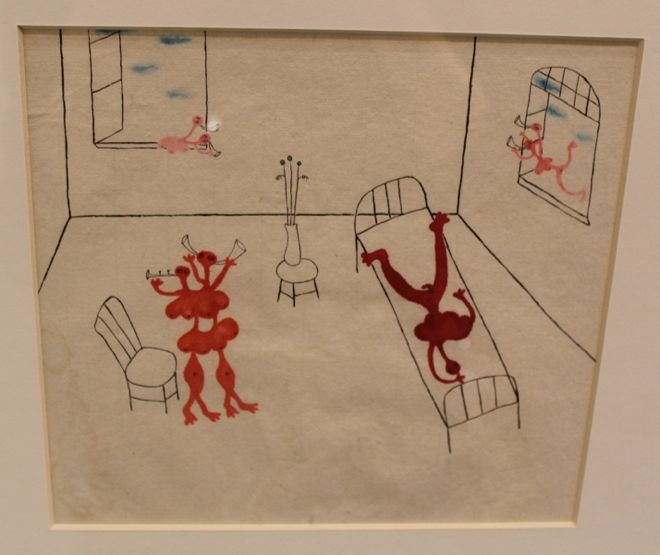

But the plunge comes in the next space, where paint and plasticine beget a plethora of figures. There are a couple of paintings which strike us with the sheer sea of beings they contain: swirling shoals of polyps which reach upward with bugle-shaped receptacles. On the opposite wall, pairs of figures with additional heads, breasts and limbs, often mounted on elongated tendrils, occupy domestic or dreamlike situations. However, a second glass case houses the real freaks: bizarre bloated figurines in a putrid pink with layers of breasts and multiple genitalia — sexualized pupae spliced together, often with several sets of legs and heads emerging simultaneously. The neon-pink “Terracotta Warriors” (2003-4) in a fluorescent tank at the end of the room marry the two figural modes, lanky and squat, in a series of lascivious, hilarious mutations in which beings impregnate each other, give birth, recline and reproduce on miniature furniture objects. For Gu Dexin, this Lilliputian society visualizes the problems of our own; in his own words, those of “the sexual difference between men and women… inflicted upon us by social conventions….” Thanks to Karen Smith’s account of Gu Dexin’s work in her book Nine Lives, we know this perverse crowd is kept carefully locked away in cupboards in Gu’s studio — sheltering, it seems, both the beings themselves and the imagination that conjures them.

顾德新:“重要的不是肉”(2012),展览现场

And then, just as these eccentric throngs had made their appearance and imparted their collective appeal, so the intimate exhibition room gives way to a giant hall of large installations — a broad static theater of Gu Dexin’s conceptualism. Clearly dictated by the balance of works obtained for this show, the sudden shift to big works, enlarged both in size and clout from the figurines and paintings, is somewhat disarming. The viewer now finds themselves dwarfed on a monumental field furnished with expansive artistic acts, though created by an artist who never wanted to be a symbol for anything. Gone is the bouncy palette of the toothed and multi-sexed creatures, replaced by chauvinistic red and the gradually expiring glow of thousands of apples dumped on a portion of the floor.

顾德新:“重要的不是肉”(2012),展览现场

Staging extracts of large installations from past exhibitions together inside one massive shed is a difficult task. A cheaply gleaming flagpole shown previously at Shanghai Gallery of Art (2005) lies prostrate like a disembodied spine on the floor. It is attended by scattered apples and the smooth red plinth from which it has been felled; as in Shanghai, it points toward a flat painted field of red hanging on the wall ahead. The whole is astutely unprepossessing. Flanking it on the right-hand wall is the chorus of kitsch dolls who in 2002 (for the exhibition “Harvest” at Beijing’s Agricultural Exhibition Center, sponsored by the city of Qixia) were left to move and sing mechanically until their batteries went flat. Now, of course, amid this environment of retrospective reverence, they are frozen, little arms eerily half-outstretched. In this otherwise still arena, the corner lined with LCD screens each playing a different video drawn from Gu’s Flash animation period in the 2000s provides the only movement. In one series, peculiar fertility hybrids — a branch of species seen earlier — flit back and forth on short tracts, floating, flapping and suckling in various shades of ripe pink against blank backgrounds. A second series is more directly sardonic, with stick-figures heads being punched by a mechanical arm on a production line. A third animation features a short sequence of a single shouting figure hurling an object at a screen; each time, a shot goes off from behind the screen in a strange retaliation.

顾德新:“重要的不是肉”(2012),展览现场

Prior to the opening of “The Important Thing is Not the Meat,” one wondered how the organizers would go about representing an oeuvre so strongly characterized by installations of fresh flesh and fruit long since rotted away in Venetian palaces, gardens in the Netherlands and in selected Chinese exhibitions. Indeed, it would have been impossible for Gu’s conceptual-art butchery to feature directly here. An undulating square heap of apples gradually decomposing is the chaste progeny of earlier Edens of decay. Hanging on the wall are ranks of gilt-framed colorred exposures of the artist’s hand pinching individual bits of pork; in a glass case before them are labelled tupperware boxes containing the desiccant cuts — kneaded beyond nourishment and substance like words pronounced over and over until spelling and sense evaporate. It is like an act of attrition against an ordinary organic substance that can stand for many greater battles.

顾德新:“重要的不是肉”(2012),展览现场

Rising like vapor from this exhibition is the tension between the mass and the single idea applied to it, as of people subject to societal mores: an army of 10,000 mini ceramic cars (“2004.05.09”), numerous meat scraps agitated in the same way over time, seething fields of painted figures…. The elephant looming large even in UCCA’s biggest room is that of the artist’s deliberate exit from art’s current apparatus, from the beautification of works in hallowed halls, curatorial kudos: the systems that sanctify works and enroll an audience for them outside individual response. Here, the organizers’ sense of the importance of Gu’s work is tied inextricably to that attached to their own role in promoting powerful art. Minus the blood and gore, the impregnated carcasses and trays of brains, here is an absorbing, sometimes startling view onto the output — from amateur paintings to the horrific frieze marking his last consensual exhibition — of undoubtedly one of China’s greatest artists, though his “contemporary” status applies not to art production now but to a sheltered life in the compound where he grew up. That Gu has left art for good lies here as a potent fact noted, but not addressed. Ultimately and, perhaps, inevitably, this exhibition is in many ways as much about what isn’t here, as what is.