By Alice Gee

Chen Tianzhou ‘Backstage Boys’

BANK (Building 2, Lane 298 Anfu Road, Xuhui District,) November9, 2019–January 12, 2020

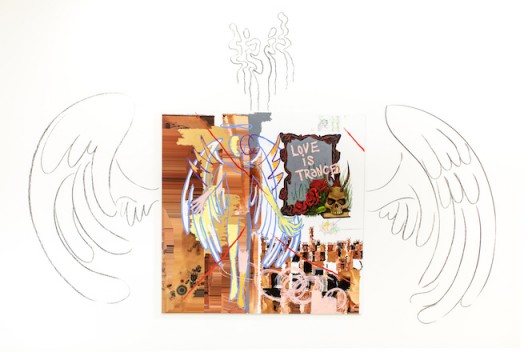

Chen Tianzhou, best known for his performance works, has dubbed himself a ‘backstage boy’ – one who spectates his art separately from the audience and ‘disappears into his own work’. In his painting debut at BANK, he tells us in the press release that ‘the backstage boy steps onto the stage’. This stage is shared with the paintings of his partner, Lu Yang, who normally works from behind a video camera. This whole exhibition is about re-positioning. Once you pass through the beaded entrance, you enter a liminal space where boundaries between life, death, man and deity dissolve into lurid spectacle.

Jingba Lost in the Forest is an inkjet print of a photograph of Ylva Falk and Beio Mao, performers from Atypical Brain Damage, Chen’s apocalyptic pop-opera. They are photographed in a bathroom and set amidst an oil stick scene of a dog lost in a forest,a scene which spills off the aluminium panel and invades the wall with tree trunks and stars. The photograph was taken after a performance and snaps the pair stripping themselves of their theatrical make-up and costumes. Falk pulls open the shower curtain and invites the gaze of the camera. Mao looks up from the sink, his makeup bleeds into red oil-stick which trickles down his body. Chen tells me that he was struck by the violence and beauty of the scene, an intimate portrait of two friends as they destruct their maleficent staged identities.

Chen calls this ‘showering off your personal ego’ and the desire to shower off the ‘ego’ seems to be shared across Chen’s id-driven, carnivalesque works. But as Falk coquettishly appeals to the camera’s gaze, poised so the curve of her waist is empathised and her breasts are uplifted, one mask slips to reveal another. If the voyeur must maintain a distance between himself and the image to induce pleasure, then Chen helps maintain this distance through fantastical illustrations which obscure the genitalia of his subjects and mythicise his subjects into a mermaid and a reptilian beast. In this ‘backstage’ dimension, hinged between the performed and the day-to-day, identity is teasingly withheld. Instead the viewer is suspended between fantasy and reality, where play and pleasure reign.

Chen’s work spills off the canvas and onto the wall, and spills off the performative self into the ‘backstage’ self or the subconscious. He also elides the boundary between the transitory and the infinite. The Lost Boy is a large MDF relief lain upon the floor like a grave marker. A small figure lies curled into a foetal position besides an engraving of William Blake’s ‘Little Boy Found’ into the crater-like, inhospitable earth. The skeletal remains of a dog are splayed in the bottom left corner. Colour is used more sparingly here, and the eye gravitates to the figure’s skull, a globe hinged upon the Americas and yet to be enveloped by the dull ground. The work is inspired by something suicidal, and the notion of reincarnation, Chen explains. All these works are kind of continuations of Chen’s performance pieces and give them – as the press release expresses – ‘a second life’. Here lies a permeable body memorialised by an impermeable marker. ‘A Lost Boy’ who will be found.

Blake was a printmaker whose art was the product of physical labour. Chen’s performance works, he explains to me, are also the product of prolonged physical labour, and share Blake’s aim to transcend into a visionary trance. To go beyond the body, you must go through it. Blake believed that the imagination was the ‘body of God’ and our bodies are vessels to God. Like a kind of communion, Blake’s spiritual work was born of the body and experienced by the body through meter and rhythm. In Chen’s modern reimaging of the poem, the exhausted ‘lost boy’is an MDF relief of Chen’s own body. We typically connotate artistic ‘Kinesthetics’ with motion, but does Chen’s imprinted body also constitute what Belgrad calls, ‘a repository of unconscious knowledge’? Chen has worked through the bodies of performance artists to realise his visions; here he offers up his own body incarnate. One flesh representing all flesh, as the globular skull suggests, lost in some hyperspace and seeking spiritual resurrection.

One piece, propped against a wall, looks like an uncanny high school art study, or the garish attempts to re-colour ancient Greek statues which have challenged the deification of their whiteness. We can Reveal the Shadow of the Shadow is an MDF relief of a shackled man with dishevelled hair, coloured with oil sticks, contextualised by a lurid green background of inexact purple diamonds and heraldic emblems of fire and herons. At the bottom of the panel, in gold lettering reads

‘you want to write, you want to speak

but you are not allowed to

only through art,

we can reveal the shadow of the shadow’.

The piece recalls a scene in Atypical Brain Damage, where two artists (the Vietnamese ‘Le Brothers’) bearing guns, crawl across the ground and try to evade the observation of sinister patrollers (Valk and Mao). They lament their position as artists: ‘it’s impossible for a westerner to understand our history’, the subtitles translate. Part of his research for Atypical Brain Damage, Chen explains, included interviews with veteran artists, from which these quotes are pulled.

The conflict in this scene from Atypical Brain Damage allegorises these discussions. Here are artists who must produce work within the constraints of what their country allows, and who may find their work misunderstood or threatened by a domineering, somewhat sinister, Western presence. In this piece, Chen, who is a graduate of Central St. Martins and Chelsea College, seems to set himself apart from the pessimism of the previous generation of artists, and defiantly writes and translates these quotes in English. This globalised optimism pervades and epitomises the collection. In this pleasurable and indulgent break from the strenuous labour of performance work, Chen reveals and stages the ‘shadow’ self. Here, between the real and the noumena, we are catapulted into a borderless ‘new material realm’. Death, chaos and desire dance like shadow puppets, somewhat clumsily, in diasporic, playful colour and pulsate with the direct energy of Chen’s painterly hand.

Alice Gee is a writer. After graduating from Cambridge University with a degree in English, Alice moved to Taicang, a city just north of Shanghai, where she writes and teaches part-time.