“Accommodating Reform: International Hotels and Architecture in China, 1978–1990″

UCCA (798 Art District, No. 4 Jiuxianqiao Lu, Chaoyang District, Beijing, China 100015), Aug 19–Oct 23, 2016

We have to be aware of the importance and conflicts of interests within spatial strategies: the relationship between “authority”, groups, administrative organization, capital and capitalists, regime, masses, and nations…etc. The internal correlations of economics with regards to politics (or vice versa) thereby obtains its effect and meaning.

Henri Lefebvre, Space and Politics, Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 2015. [Translated into English from the Chinese translation of the French]

Two months ago, one evening in mid-August, a “round table” discussion on the theme of architecture took place at Taikang Space. Upon the strong request of the organizer—the mysterious intellectual collective called pills—the event was not promoted at all before it happened. In the white box space defaced beyond recognition by a camera crew that forced its way in with all its lighting equipment and cameras, a group of people dressed in black and from different domains got embroiled repeatedly in topics such as architecture and “spatial capitalist subject disciplinary pragmatism theory”… all of which could be summed up, to use the words of a participant who occasionally dozed off, as making those already opaque terms even more obscure. The rise of 20th-century architecture as a subject, in both theory and practice, also signifies a kind of inevitable surplus production, not only in terms of architecture itself, but also architectural discourse, the recent deluge of which has, to a certain extent, precipitated the production of this essay.

Yes, this text is fundamentally a critique of discourse directed towards a new model of discourse as a combination of architecture and exhibition (something that did not exist in China until about twenty years ago). Prior to this, how had architecture been packaged into discourse and disseminated? For example, the tenth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1959 spectacularly announced the capital’s “Ten Great Buildings”. These temples of massive scale, brimming with nationalistic fervor, were not openly accessible to everybody, however (at the time, residents of other provinces needed a permit to enter Beijing); thus they had to be represented, translated, and disseminated in order to effectively reflect the key ideological import behind the architecture. Architectural discourse of that period, including photography, periodicals, propaganda posters, newsreels etc., was a unified and instrumental discourse originating in the regime of the People’s Democratic Dictatorship. Critique of instrumental discourse can only remain at the level of technique and policy, in the same way that it was impossible to critique the sickle: it could kill, but it could also cut grass.

True critique can only proceed when architectural discourse rids itself of the triteness of instrumentality and enters into (quasi) autonomy, reaching a point where presentation merges with expression in a complex and multi-dimensional space. In this essay, the subject of evaluation is intimately bound up with the historical moment of such a turning point. The end of the Cultural Revolution, the loosening of society, the implementation of the policy of Reform and Opening, as well as the conversion to new modes of thought: such are what the exhibition “Accommodating Reform: International Hotels and Architecture in China, 1978–1990” at UCCA presented as the historical and social backdrop to the construction of the seven hotels. As the landmark architecture of the time, these seven sample projects—the East Wing of the Beijing Hotel, Beijing’s Jianguo Hotel, the Fragrant Hills Hotel, and the Great Wall Hotel, as well as the White Swan Hotel in Guangzhou, the Jinling Hotel in Nanjing, and the Shanghai Centre—hold a concentrated significance in their spatio-temporal dimensions. Looking at historical traces, they make for a vivid comparison with earlier ideologically informed architecture. In terms of spatial logic, they connect Communist countries of the mysterious East with the capitalist world of the West.

As the exhibition text stated: “As Chinese officials, architects, and planners worked with foreign investors, designers, and developers to define, articulate, and control the contours of the country’s reform agenda, new types of cross-cultural exchange took shape within international hotels around the country.” As a reformulation of architecture, this exhibition entitled “Accommodating Reform: International Hotels and Architecture in China, 1978–1990” defined “reform” and “cross-cultural exchange” as the tasks given to these buildings and the stage upon which they play their roles. This means that such material substance, as the combination of each and every material, can only be truly established in its reliance on that seemingly ethereal assemblage of political, economic, social, cultural, and psychological events and chain of connections. Architecture is made up not only of material substances, but also people—those who use, experience, and serve it—as well as the relationship between these people and architecture, for they enter relationships with others by virtue of the building, thereby allowing complex social relations and all discourse surrounding architecture to unfold and disseminate. The complexity and diffusion of these networks of relations cannot be exhaustively listed. What this exhibition tried to encompass are the two polarities of architecture, one as material entity and the other as meaning and relations. Yet the problem also resides in architecture’s vacillation between these two polarities: although it is not lacking in miraculous insights, it also presents regrets. In the exciting moment when artworks and textual materials illuminate architecture’s dual quality—not only as something experiential and concrete, but also the generator of social relations and imagination—it is as though we can visualize the network of memory contained within this socio-psychological space. And it is the sites that are the most ambivalent and flimsy that make us more attentive—just as the introduction said, this text is a critique.

This critique is firstly aimed at a kind of weakness found in overemphasis of the material existence of architecture and over-reliance on historical moments. Admittedly, with regard to the showcasing of architecture, blueprints, photographs, and models are important materials—not only due to the necessity of portraying a kind of reality, but also, perhaps, that they are witnesses to a true architectural entity existing in reality. They are also placeholders in the exhibition space, announcing for architectural discourse the undoubted visibility and palpability that real and material architecture has in its inseparable geographical and social domains.

But this exhibition was by no means complete and sufficient in such a regard. Firstly, the urban views and specific environments that these seven hotels were rooted in were missing from the show. The reason such information is so important is that it [the information] has not only bypassed the scope of background and undertone, but also fundamentally binds an existing building to its geographical knowledge and sociological common sense. How does a young international hotel built in Guangzhou differ from hotels that had been put into use in the capital in the ’50s, but partially changed appearance through expansion and transformation in the ’80s? How, then, were the two intricately influenced by geographical differences? Even if these hotels were in the same city or if the distance between them were not so great, how would these hotels have been different in terms of design, function, and intent? After all, architecture does not exist in an idealized, homogenous Euclidean space, but is rather distributed in natural, historical, and social conditions that are specific, multiple, and differentiated. And it is only amid those conditions that the task and function of cultural exchange can take place, be activated, and proliferate.

Secondly, even if this exhibition limited its observational scope to the materiality of architecture, the related visual documentation suffered from the suspicion of a lack of wholeness. Certainly, the audience could still view visual-textual documents of architectural scenery, interior views, and human activities, and this visual evidence was given nearly equal space for almost every individual example. It is worth considering that all of the images concerning the exterior views of these hotels were shot at the beginning of their construction in the early ’90s, and thus these photographs or reproductions, the color and quality of which have undergone great change, seem to have captured some kind of historical flavor. Accompanying the exhibited publications were historical documents: they were all published twenty or thirty years ago, each announcing the presence of a historical period as evidenced in recipes, commemorative booklets, monographs…etc. However, this indicates another problem: surely the history of architecture cannot be limited to the initial stage of its construction or management. Is it that only such an “originary moment” could be declared as legitimate, and thereby be given special rights to be written about and historicized? The few decades that these hotels have lived through ought to be recognized and observed in their entirety; the sum of the events coming out of the ties, collisions, derivations, and diffusion of these buildings should at least be valued equally as the initial period in which they have been completed and put into use. We are compelled to ask what it is that makes a once-rich history constantly look back, restore and purify itself, so much that we can only observe and reflect on a single point on its temporal axis? Though this point had once been point of origin, we can see today, of course, that narratives concerning the notion of origins, zero, and beginnings have become myths in themselves.

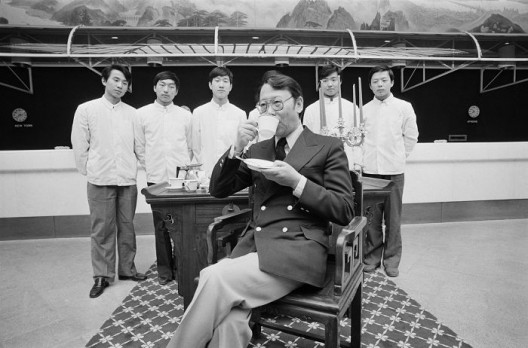

Undoubtedly, the curator of the show meticulously selected relevant materials based on the characteristics of each project—not only about the buildings, but also materials that hold historical significance, including artworks, publications, and general objects. Among these artifacts were photographic works by Wu Yinxian, Liu Heung Shing, Andy Warhol…etc., evening gowns designed by Pierre Cardin (who debuted in China’s first public fashion show at the Beijing Hotel in 1979), as well as an issue of China Comment (Banyuetan) published in 1983 featuring a photograph of the Guangzhou White Swan Hotel as its cover. These materials have special significance because of their epochal backdrop, for they are the condensation of a particular historical moment: what was once a closed country behind the iron curtain had actively unveiled itself; it was the beginning of exchanges with the West. On the level of signification and symbolic meaning, these buildings were all constructed at the beginning of the ’80s, when the Reform and Opening policy had just begun to take effect, along with the continuous boom of tourism and foreign trade. They formed a new urban landscape with aesthetic elements of modernization and nationalism, affirming the fruits of Reform and Opening, representing the new outlook of economic development, and symbolizing China’s friendly relations with the world—especially the West, which had previously been categorized as belonging to the capitalist camp. As the preface to the exhibition mentions, between 1978 and 1979, the number of international tourists in China leapt from 1.8 million to 4.2 million. Though this information is certainly important, the profound meaning of these hotels and the changes they brought about were by no means solely in the service of foreign tourists. The image projected by these modern buildings in the hearts of Chinese people at the time is worth examining and excavating in order to enrich and reconstruct a sociology of architecture. Equally worth our attention are local residents’ daily experiences, which we can infer to be vastly different from those of now. Take the Beijing Hotel, for example, the oldest international hotel in China’s history, up until the mid-’90s: those who were not hotel guests, the majority being Chinese, still needed an invitation to enter the hotel. Though these hotels were once seen as representing the disintegration of ideological oppositions towards the end of the Cold War, as well as of the rise of consumerism, trade, and global capitalism, there is not necessarily only one method of interpreting their specific contexts within Chinese society.

If we take architecture as the assemblage of physical-psychological-social spaces, then the observation and representation in its research should equally be multi-dimensional and multi-faceted. In such a complex social object, its material shell must bear a function and become a center for the production of social relations on account of human usage. Architectural plans and models prioritize structure and static parts, and cannot present complex, flowing, and changing social relations; the latter, according to Lefebvre’s opinion, though often neglected, plays important roles in interpretation, changing the environment, society, and even the world. Just as this exhibition focused on “reform” as a keyword, it also touched upon the fact that these seven architectural cases were actually suffused with the imagination, experimentation, and negotiations of “reform”, manifest not only in the already completed hotel buildings, but also in each specific stage—commercial negotiations, engineering developments—undergone by different subjects over the entire course of construction.

“Reform” is not only a dominant symbol of modernization and internationalization, but also of all kinds of relations coming out of its encounter with people; what took place during this period were not only cross-cultural exchanges, but more importantly the sum of all social relations: not only cross-cultural, but also the “glocal”. In this exhibition, we witnessed the history of these buildings—a complex synthesis of materiality, pictoriality, and symbolism—but for Chinese audiences who have experienced these historical circumstances and developments at first hand, the narrative here seemed too simple.