“A Potent Force,” duo show with Duan Jianyu and Hu Xiaoyuan.

Rockbund Art Museum (20 Huqiu Road, Huangpu District, Shanghai). Jan 26 — Mar 31, 2013.

This dual artist show at Rockbund Art Museum features two female artists, Duan Jianyu and Hu Xiaoyuan, both in their late 30s and early 40s. At first glance, demographics and gender alone seem to hold them together. Hu Xiaoyuan’s work is muted, subtle and process-driven; Duan Jianyu’s is bright, bold, and in some works verging on garish — the figurative foil to Hu’s abstractions. Despite these obvious stylistic differences, what unites them is their focus on interior worlds, and their meditations on time, perceptions and the surreal.

That said, the strength of this show lies not so much in the dialogue created between the artists but the strength of the individual works. Standouts in the Duan Jianyu’s half of the exhibition include “The Lonely Shepherd” (2012). The work features a series of knolls on which roam a number of sheep, all in different forms and colors flanked on the right by an ill-tempered herdsman wielding a whip which spirals up into the heavens. Emerald hills are set off against a background of cream, all rendered in a variety of different painting languages from the naïve to the impressionistic. In this somewhat surreal landscape, the ridges fade from a dark emerald to a whitish grey and are marked with rivulets of water which look like rivers drawn on a handmade map. There is something akin to Georges Braque’s earlier Fauvist landscapes in the compositions and color scheme of this work— the combination of schematic lines with gradients which are used to suggest volume. While the hills in the foreground feel somewhat three-dimensional, those in the background are just mere line drawings as if the painting is in an unfinished state. On the hills are placed various sheep, lying down, nursing, giving birth or peering quizzically at the shepherd. The painting however is dominated by what seems like a “non-sheep” — an inky black outline which looks like a black-hole in sheep form. It is this sheep at which the shepherd seems to be aiming his whip.

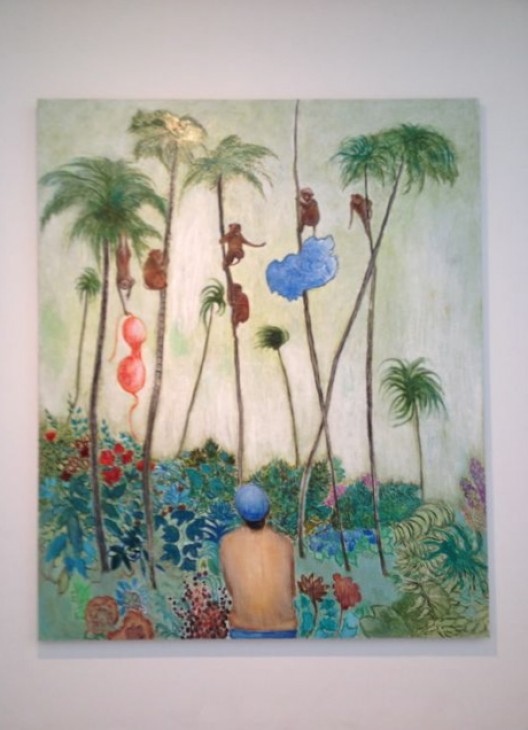

One might perhaps be tempted to give this a political reading (i.e. black sheep dissenting opinions etc.), but the rest of the works on display would not indicate this. Rather the rest of the work focuses on relationships between animals and humans often with heavy sexual connotations. Also intriguing was “Sister No. 18” which features a figure seated in front of palm trees festooned with monkeys, one who dangles a cartoonish bikini top as if the cheeky primates have made off with the clothes of a skinny-dipper. Duan Jianyu’s work is filled with such innuendo — situations which feature the female body in semi-erotic poses — but then again the women are somehow devoid of the air-brushed perfection of the actors found in pornographic material. For instance in “You Are Welcome” (2009), a woman sits on a rock, her torso bound in an artful web of ropes, but her face and body are very plain if not awkward, a slightly paunchy belly and a nipple pointing skyward distorted by the tension of the ropes.

This woman and others in the painting are surrounded by a great number of chickens and one wonders if there is not some studied juxtaposition — the word chicken (ji) being slang for prostitute — but the other women do little to clarify this connection. Another woman, also nude, is engaged in a yoga pose, while another cradling a child in one arm is nursing a puppy — this all set in a natural landscape of meadows and forests populated by many chickens and geometric forms. The juxtaposition of nude women in a natural environment seems allude to the idea that sex is a natural act. Perhaps that’s too literal of an interpretation, but either way it’s very refreshing to see nude bodies depicted in a way that’s not semi-pornographic/erotic — a phenomena which seems to dominate a lot of Chinese paintings, from the kitsch offerings at the Moganshan Lu to the Chinese auction houses.

It is all entirely possible that that nude women have no symbolic meaning and serve rather to convey humor or a sense of the absurd. This is perhaps best conveyed in “A Pair of Embroidered Shoes No. 3, The Wordless Ending,” 2011 which features a curvaceous landscape in naïve painting style in white and black with a cottage placed in the middle — the punchline being that each hill is topped with a black nipple as if the topography was composed of a cluster of women lying down shoulder to shoulder. This work is perhaps more interesting in some ways taking us into the mind of an extremely over-sexed individual which sees erotic stimuli in every mound and molehill.

Though there are some very exceptional pieces in the show, Duan’s output is quite inconsistent. A prime offender would be “My Name is Red, N0.2 ” (2010) a painting of Santa Claus with bunions reclining in a chair; coming in a close second is “Beautiful Dream: The Daughter of the Sea” (2008) — a woman perched atop a rock silhouetted against the sunset which looks like the kind of painting that you might buy in a Waikiki tourist shop. The fact that it’s surrounded by hand-made maps of Hainan on fruit boxes would make one suspect an ironic intent, but somehow it doesn’t manage to pull it off.

On the other side of the spectrum, with a subdued palette of blacks, whites and browns is Hu Xiaoyuan’s work. Where Duan channels the modern painters, Hu seems to make reference to Chinese traditions of ink and xuan paper. In “Axing Ice to Cross the Sea,” a three-channel video piece, we see what looks like a winter horizon at dusk on the left channel, while the center channel depicts what looks like the border between an ice-shelf and open inky black ocean. This image, however, soon morphs into an ink-soaked cloth shiny and tar-like shot in a macro format. On the right we see what looks like some organic form — maybe coral which bleeds in and out of focus from the figurative to the abstract. Though the visuals are strong, the focus of this work is not entirely clear, as is with “Drown Dust” (2012) a piece with a figure doing some kind of freely interpretive movement in front of a waves while another camera pans the snowy ground.

This slow and meditative style permeates her work and but it seems to be more successful in her installation pieces. Viewers entering the second-floor space are greeted (albeit not very warmly) by a number of sections of planed-logs and drift-wood covered in a silk veneer. The works were created by first placing a layer of raw silk on the wood then painting over the grains of the wood with ink. After removing the silk veneer, Hu slowly carved away the existing layer of wood, so that all that remained of it was the phantom silk imprint of the wood. On a purely aesthetic level, “The Vortex Beneath the Vortex” causes the viewer to ask questions about form and technique but it’s also about absence and presence and of course transience. Another work which picks up this theme is “Useless,” a long scroll of rice paper torn up and then patched together with tape — the effect looks almost like a cracked porcelain glaze (actually known as crazing) which was developed in the Song Dynasty. While viewing the work the observer starts to discern a faint noise which sounds almost like the shuffling of feet but is actually the artist tearing up the paper in the process of creating the work. Here as in other works, she forces us to strain our capacity for concentration in order to tease out the truth of the situation from what our senses perceive as reality.

We have a reprise of this theme in “See” (2012) which features a blank white screen with a white line which slowly moves from right to left. The leading role in this abstract video is a piece of xuan paper. The point, as explained by the very helpful RAM volunteer, was to force the viewer to slow down and contemplate, but the whole “beauty requires patience from the beholder” came off as slightly pretentious. If I am going to wait ten minutes for something to happen, I want to be wowed.

Still there was plenty of wonder readily available. Perhaps one of the most charming pieces was “Summer Solstice” (2008), a small desk with a drawer full of cicada chrysalises and a roll of xuan paper which made sinewy connections back to the previously discussed wood and silk pieces. While this all felt very literati, the objects on the desk felt distinctly 1980s. Though very ordinary in their nature — an ornamental plate, books, a Bambi figurine, a pair of keys — they were constructed out of (toilet) papier-mâché. Bearing a texture which is both rough and handmade yet highly refined at the same time, these objects force the viewer to contemplate their composition looking like they could easily be made out of ceramics or styrofoam.

The use of toilet paper adds a hint of humor to this very somber installation and also underlines the contrast between our contemporary throw-away culture and the timelessness of ancient literati ideals. The silk overlays on the wood bear testament to the past of the wood and the xuan scroll is itself a reconstruction of a scoll of the past, which was once whole, then shredded, then became whole again (with an audio track reminding us of the process of fragmentation which it endured). Using these fragments, Hu constructs a poignant mediation on time, nostalgia and the fleeting nature of our current reality.