“…since 1999″: Yang Shaobin solo show

Alexander Ochs Galleries (Besselstrasse 14, Berlin) Sep 21–Nov 23, 2013 (extended)

Furnace-hot people, molten, abused, abusing, filled the paintings of Yang Shaobin (b. 1963), televisual violence and internet grotesquery playing to our sadomasochistic scopophilia. You couldn’t look away.

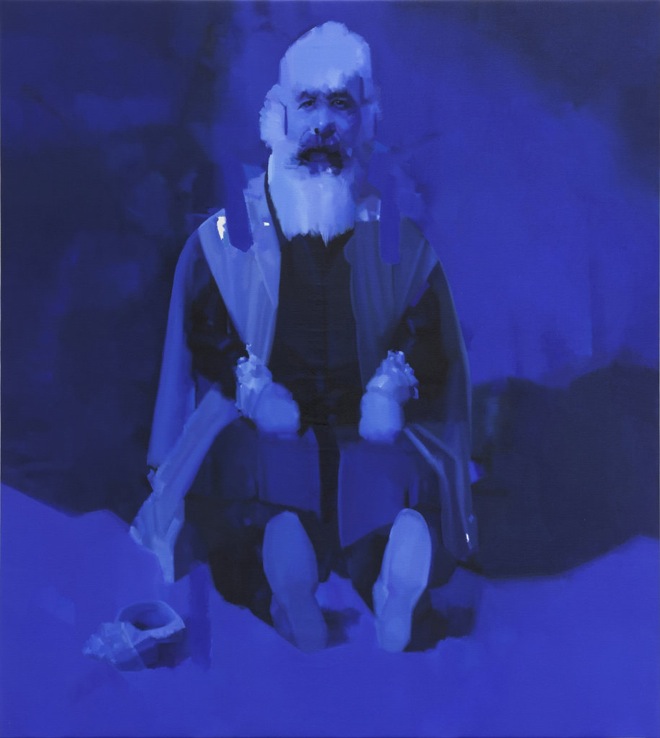

In 2009, he began exploring the other side of these images, removing the heat. They are still figurative and preoccupied with violence, but have shifted to a lower and colder register. His recent Berlin exhibition at Alexander Ochs Galleries showed nine new, large-scale paintings — blue monochromes. These “photographic negatives” look intensely at surveillance and the subject’s moral response point. The heat-sensitive camera is on, but no heat is detected.

杨少斌,《无题》,布面油画,190 x 170 cm,2013

There are also quotes from the two most famous Spanish artists of the Late Renaissance and Baroque periods, Velazquez and the Cretan-born El Greco. The former is noted for his humanization – democratization? – of the then-prevalent tradition of idealistic representation, and the latter for his manipulation of form, particularly by stretching perspective and using strong color. Flagging such quotes so deliberately, Yang is simultaneously stating a case for looking at art, its moral role and his place in the painting canon. A mouth is left open in a Baconian scream (a Velazquez dwarf, with a hint of Marx); a masked and helmeted riot policeman observes from the turret of an armored car; a close-up of a young child, agitated, shows her watching something.

The paintings are very much about painting. White holes have been left in the blue skins, or painted onto them – here an egg shape, there the minute reflection on the tip of a nose. A shell lies at the foot of the seated dwarf, drawing attention to its interior space and infinite surface. And all over there is this luscious mélange of blues – including Midnight, Ultramarine, Cobalt and Prussian – not pellucid but deep, emotional and confusing.

杨少斌,《无题》,布面油画,140 x 180 cm,2013

杨少斌,《无题No.2》,布面油画,280 x 210 cm,2012

The key work in the series — the only one with any color besides blue — shows an ordinary man wearing a camouflage jacket, against a wall, in a defensive pose and with a resolute face. His foot transgresses but does not overstep a thin red/green line. He stands in a pool of pale blue light that climbs the wall. Or maybe there is no wall, just darkness – the spatial context is deliberately ambiguous, even recalling Barnett Newman’s zip paintings. The expression “the thin red line” originally came from an incident in 1854 during the Crimean War, in which a small group of British infantry routed a Russian Cavalry charge despite the odds against them. In 1892 the English writer and poet, Rudyard Kipling, used the line in a poem about the lot of the ordinary British Soldier, in slang called “Tommy Atkins” or “Tommies”, as popularized in the First World War. More recently, “The Thin Red Line” was the title of Terence Mallick’s celebrated 1998 film about U.S. soldiers in Guadalcanal, fighting the Japanese imperial army. In the pivotal closing scene, one soldier sacrifices himself to save his comrades. The “thin red line” in Yang Shaobin’s portrait, then, has various references, but these are not ambiguous. The “thin red line” in Kipling’s poem indicates another demarcation. Writing on Mallick’s film, David Thompson in The Guardian recently noted that it is also the line that separates the sane from the mad.

杨少斌,《无题》,布面油画,85 x 80 cm,2013