Practice (111 Eldridge St, New York, New York 10002), Jun 30–Jul 10, 2016

“How is the Weather” came about thanks to conversations between Song Ta and the exhibition’s curator, Ho King Man. An aimless atmosphere free of refined thinking thus evoked served somewhat as a safe, casual starter. The sense of relaxation and openness is in tune with the ethos of Practice, a small but very active non-commercial project run by Ho King Man, Cici Wu, and Wang Xu which supports a residency and monthly exhibition openings in a Chinatown apartment.

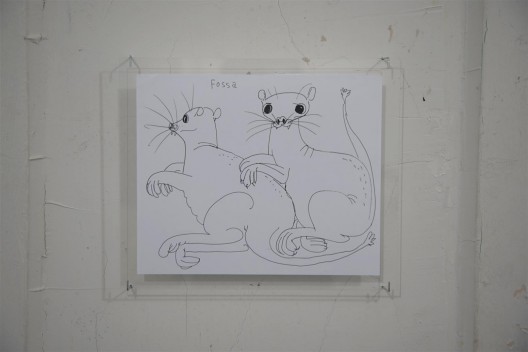

Here, Song presents his calligraphy along with three pen drawings and one exam paper (not his) with a perfect score that is suspended from the ceiling in the middle of a room. Ho King’s thoughtful installation shouldn’t go unnoticed: twists of electrical cable under display screens were deliberately left visible to echo the movement of written characters; in playful acknowledgement of the suggestion that expert calligraphers are learned in general while less is expected of those who draw well, Song was encouraged to show his cartoons of animals. With simple black line, these deliver a flair for shape and his enjoyment of the demeanors of creatures.

The calligraphy (shown mostly as digital images) inscribes unrelated fragments—”Rotate resize select paste drag into wind crab by the street eat what what”—and copies quotations (from Mao Zedong’s “A Little Spark Can Kindle a Great Fire” or the great “wild grass” calligrapher Huai Su’s Autobiography (Zixu Tie)) or other extracts as an excuse to practice writing. That no reason was given for the choice of texts contributed to a certain feeling of detachment around the display—a lack of context (or the need for it) that in some way echoed the mood of its name.

“Perhaps the only decent calligrapher in Mainland China in the past two decades” was Song’s idea for a title. Equipped with this attitude and a trove of gawky, unbalanced, sprawling characters, he put up what could be called a “bad calligraphy” show after Marcia Tucker’s now-historic 1978 exhibition “Bad Painting” at the nearby New Museum, which asserted a positive, liberal attitude to the mixing of art historical references. But while “Bad Painting” featured “artists who consciously reject traditional concepts of draftsmanship in favor of personal styles of figuration” as Song does for his characters—this is certainly a tease aimed at the calligraphy establishment—Tucker also felt the bad painters’ work bypassed aesthetic progress as a goal affecting the determination of value. While his writing is irreverent, Song would like his pieces to be considered and properly appreciated (indeed, he invites their “review”, and the exhibition includes a video of a child remarking on his writing and comments from an artist friend who responded with her own calligraphy). For him, to entertain this calligraphy would be a step forward, though it’s not clear whether he wants this for himself alone, or the discipline in general; again, Song’s sphere of reference is only minimally sketched.

His approach might more simply be a “deskilling” of his own. The term was first used in hindsight (by Ian Burns in his essay “The Sixties: Crisis and Aftermath (Or the Memoirs of an Ex-Conceptual Artist)” in Art & Text in 1981) to appraise artists like Seurat in the late 19th century who invested new energy in their work partly by fritting away at the idea of virtuosity (in so doing, in a sense “de-historicizing their art”); in this lay the kernel of fine art’s challenge by industry and the consequent turn against manual as opposed to machinic or “readymade” effects—one deepened by the possibilities of photography. There followed the self-conscious rejection of technical drawing and other skills at many western art schools.

Though his anti-academic stance is nothing if not low-key, Song clearly has no interest in emulating master calligraphers or perpetuating formalism. Then again, neither do his scrawlings here suggest a path away from the individual hand— quite the opposite. He seems quietly confident, and like a lot of his work, these writings harbor a certain scorn clad in deadpan humor and an inclination to simply do something, and share the results. Song’s amiable, “dysfunctional” characters are thus very much in-character—they best convey an art of attitude, the hopes of which begin and end in the moment of making.