Lu Chao “Black Box”

Hadrien de Montferrand (98 Art District, No 4 Jiuxianqiao Lu, Chaoyang District, Beijing), March 11–April 8, 2017

The smile is a cliché of contemporary art in China. Apparently, anyway. Geng Jianyi (b. 1962) was probably the first to employ it, in works such as “The First Series of Eight Steps” (1991), where the line between ecstasy and anguish in his self-portraits is indistinguishable. A similar approach was taken by Yue Minjun (b. 1962), who made laughing self-portraits his signature and he is still haunted by them. Meanwhile, the masks of Zeng Fanzhi (b. 1964) sometimes laugh but not always. Often the laughing face is interpreted in the West as simply an ironic pop-gesture, and increasingly as an empty gesture. Often artists in China are happy to let this misinterpretation slip by, because the purpose of the laughing face is precisely to mask. And there really have been a LOT of smirks.

The smile is generally ambiguous as to meaning (thinking of the Mona Lisa), whereas depictions of laughter, when not simply cartoonish and idiotic, are ambiguous as to feeling—ecstasy, agony, madness, death. This distinction was concisely articulated by the critic Lessing in his essay on the Laocoön (1766)*, wherein he noted that in the famous Roman sculpture of the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons Antiphantes and Thymbraeus being overcome by sea serpents, the figures faces are relatively composed with mouths not wide open. Lessing argued that the artistic impact of the frozen scene would have been lessened had Laocoön and his sons been depicted with wildly gaping mouths, essentially making them look less human, less god-like, more animal-like. Considering Munch’s “The Scream” (1893) and Francis Bacon’s series of screaming popes, Lessing maybe had a point—or perhaps missed one.

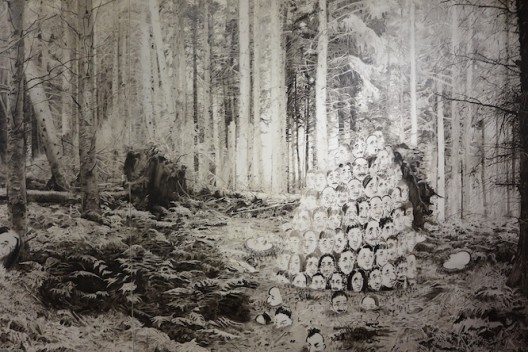

Lu Chao’s “Black Box” exhibition earlier this year raises the point in another way. The exhibition revolved around an operatic brush and watercolor forest tableaux in which severed heads are piled up and precariously stacked to form totem poles—not actually dead, mind you, as they all seem to be quite aware of their situation. Scurrying around on the ground, working at some of the heads, are anonymous and ant-like figures. Each head, though, has personality. Some smile even. More importantly, they are caricatures—really likenesses of familiar types of people; your aunt, your teacher, your neighbor. There is a scene in Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children where one of the protagonists has a conversation on a battlefield with the stacked heads of his former friends. Are we laughing or crying?

“The horror! the horror!” are Kurtz’s dying words in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, their meaning left unexplained and uncertain. The absurdity and ambiguity of “Black Box” work in similar ways. The theatricality of the forest setting, the moody light, the quiet shadows, set us up for a sublime release, the fabulously romantic delusion of nature as pure, unadulterated and god-given. Move closer though, and we meet its ridiculous, disembodied inhabitants. Death is stupid (and don’t we know it today). All those caricatures—all those characters—rendered naturalistically would not have more meaning. Deft brushwork makes it all seem so seriously funny. Do you recognize anyone?

*Full title: Laocoön. An essay upon the limits of painting and poetry. With remarks illustrative of various points in the history of ancient art.