By Luise Guest

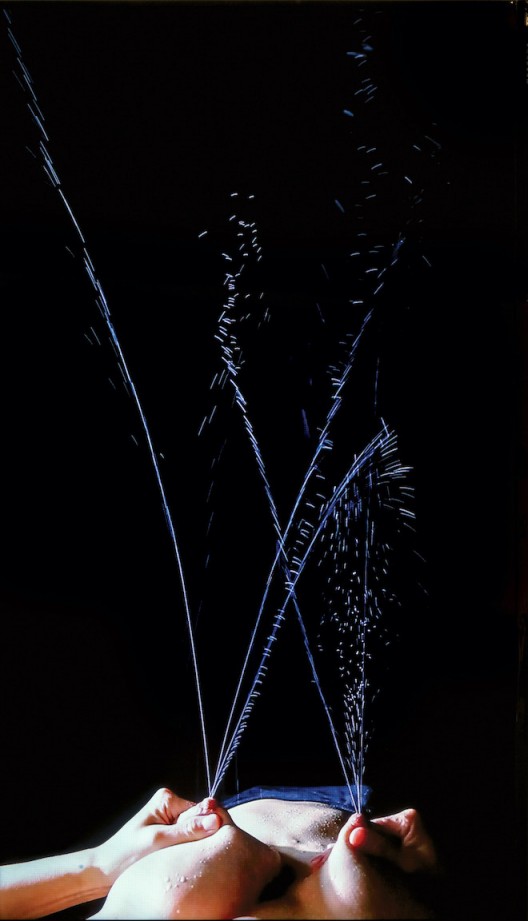

A naked female torso is half obscured by shadow. We cannot see her face. As her hands rhythmically squeeze her pale breasts, jets of milk shoot into the air. ‘Fountain’ (2015), a video first exhibited at her graduation show in 2016, brought young artist Cao Yu instant notoriety. Viewers reacted viscerally – some with outrage and disgust, some with anger, some with fascination and delight, and some with bewilderment. Was it pornography? Was it a joke? Was it a feminist statement about motherhood? Reactions to this work, including an attempt by authorities to remove it from the exhibition, reveal so much about how women’s bodies and their sexuality are perceived. Cao Yu’s transgressive work issued a defiant challenge to ingrained cultural taboos, that is for sure.

Minimalist, conceptual, and deliberately provocative, Cao’s work reflects upon and exploits the physicality of her materials, from the conventional – marble, stretched linen and canvas – to unexpected, even transgressive, substances including the artist’s own hair, breastmilk and urine, and their various significations. Cao graduated from the academically rigorous Sculpture Department of Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts and cites Sui Jianguo and Zhan Wang as influential teachers and mentors. In a recent interview Cao Yu said it was Zhan Wang, whose own work is deeply conceptual and uncompromising in its refined physicality (1), who encouraged her to realise her potential when she began postgraduate study.(2)

Single channel HD video (colour, silence)

11’10″, edition of 10 + 2 AP.

Image courtesy the artist and Galerie Urs Meile

Font of Wisdom

Despite dramatic lighting that creates a Caravaggesque chiaroscuro, ‘Fountain’ is no art historical Madonna. It is real and a bit disturbing. For me, it evokes memories of breastfeeding two babies, of painfully engorged, inflamed or leaking breasts. Lactation makes people uneasy. Bizarrely, it often evokes disgust. Even today, breastfeeding women in public are required to cover themselves discreetly with precarious arrangements of shawls, and are often pressured to remove themselves completely from the public gaze. Cao Yu’s video bravely defies such patriarchal, squeamish nonsense, forcing us to watch her female body doing its thing.

Obviously, the title refers to Marcel Duchamp’s notorious challenge to the art establishment in 1917. ‘Fountain’, a porcelain urinal turned on its side, is a sly reference to gendered sexualities, a hand grenade thrown into art history and over a century later it is still the subject of contested interpretations. Cao Yu also references Bruce Nauman’s ‘Self-Portrait as a Fountain’ (1966–1967), in which he spits out an arc of water (with obvious ejaculatory symbolism). Cao’s breastmilk fountain satirises the phallic subtexts of both works.

Cao Yu’s uncompromising chutzpah in confronting the masculinist history of modern and contemporary sculpture and performance art – so much testosterone! – echoes the similarly audacious work of a Chinese performance and transdisciplinary artist of the previous generation. In 2001, He Chengyao removed her shirt to stride bare breasted along the Great Wall. It was, she says, an impromptu performance during the public exhibition of German artist H. A. Schult’s installation of life-sized figures constructed of consumer waste.(3) When the semi-naked He Chengyao suddenly appeared in the midst of the crowd, attention was immediately diverted towards her. Because her spontaneous action was so public, and because it took place at this site – a potent symbol of Chinese nationhood – the considerable media attention was mostly negative.(4) She was accused of being an immoral attention-seeker, a judgement rooted in a misogynist view of ‘good womanhood’ that has not noticeably abated in the twenty years since. Some years ago, reflecting on her motivation for this transgressive action, He Chengyao told me, “Faced with all this hostility I tried to figure out the reason behind my performance. It was as if I was being controlled by a supernatural power of some kind. I decided to look inside for answers instead of outside.”(5)

This sense of looking ‘inside’, feeling an uncontrollable imperative to use her body as a means of artistic expression, is familiar to Cao Yu, too. Cao gave birth to her first child in 2014. Childbirth and motherhood changed her view of her own body and herself; a visceral female physicality found its way into her work. ‘Fountain’, Cao says, was a work that she had to make. After her child was born, for the duration of her lactation, she had frequent bouts of mastitis that caused high fevers and almost unbearable pain:

Although it caused me pain, it also brought nutrition and life energy to my child, so my milk became this wonder substance that I [both] loved and hated. So, in the process of fighting this pain, I was sensitively aware that my body at this moment was full of endless life energy and explosive force. I felt for the first time as a woman that my body could have an even more violent power to release tension than a man’s. And [if] my body was gradually turning into a masculine fountain monument, then it [also] became a container for life-giving and spraying milk. The white milk was imbued with the memory of love and hate.(6)

The video is shot from the point of view of the artist as she gazes down at her own body, experiencing its power. Undoubtedly there is an erotic charge in the work – certainly the physical closeness of breastfeeding an infant can be intensely pleasurable as well as sometimes extremely painful. But in a contemporary culture in which the breast is commodified as an erotic object, and sexuality and motherhood are often seen as incompatible, ‘Fountain’ issues a challenge to the pornographic gaze that reinforces this binary. Cao Yu wanted all attention to be focused on the jets of liquid shooting into the air and the power of her body to expel it with great force. The milk fell into her eyes, almost blinding her. Cao carefully directed the lighting, camera angle and the positioning of her body:

We chose to shoot this video with the brightest light exposure possible, which created a clear contrast between the white milk and the dark background. The details of the breasts were gone, instead, it showed a beautiful landscape of two active volcanoes.

Cao was in so much pain from her engorged breasts by the time the video was shot that she felt they would explode. She experienced exquisite relief as she began pumping, until the last drops of milk were gone. Tension and release, and that strange mixture of joy and sorrow familiar to all new parents, are communicated so powerfully in this work. Cao Yu knew that ‘Fountain’ would evoke strong reactions (undoubtedly, at least in part, her intention) but her video is not merely subversive, it is also aesthetically beautiful.

Such candid representations of motherhood are rare. We are more accustomed to saccharine depictions of selfless maternal sacrifice, or airbrushed, Instagram-perfect imagery that belies the bloody reality of childbirth, the delirious exhaustion and pain of new motherhood and lactation, or the endless, repetitive labour of raising a child. It is no surprise that the work excited controversy when it was exhibited – indeed, Cao Yu says she suddenly knew what it was like to be an overnight sensation. Some members of the art academy’s administration tried to prevent the work being shown at all, declaring it to be pornographic. Her name was abruptly withdrawn from an awards list. Members of her family were embarrassed. Audience reaction was mixed, and she was attacked online, in terms reminiscent of those used to attack He Chengyao almost twenty years earlier. Cao described the scene:

In the museum, someone was whispering in front of the work, someone called friends to come back and watch it again and again, some people were pointing fingers with bad intentions, there was also someone bursting into tears during the viewing.

I wondered whether the references to Duchamp, Nauman, and the problematically masculinist narratives of art history were at the forefront of Cao Yu’s mind as she planned this work, or whether they had revealed themselves only once she saw the video. In response, Cao quoted the Chinese idiom ‘to paint a dragon and dot the eyes’ (huà lóng diǎn jīng 画龙点睛) meaning ‘to add the final finishing touch’ to something. From the moment she decided to make the work, Cao realised that she was entering a dialogue with art history, not just with Duchamp and Nauman, but also with earlier works such as Ingres’ ‘La Source’ (1856), a neo-Classical painting depicting an idealised nude woman holding an urn spilling water balanced on her shoulder. The Chinese title of Cao’s video ‘泉’ may be translated as ‘Fountain’ but also refers to a spring or source of water. She says:

These classics have one thing in common, namely, they all came from the interpretation of ‘Fountain’ by the great male artists in art history. Therefore, the video work Fountain, created using new media, and from the perspective of a female artist from a younger generation, launched a new understanding and interpretation of the classic works in history, which was a leap forward, and that really excited me.

Image courtesy the artist and Galerie Urs Meile

Formation

‘Fountain’ transformed the milk produced by Cao Yu’s body into an art material. ‘Artist Manufacturing’ (2016) makes this intention even more explicit. Cao condensed eighteen litres of her breast milk into a malleable, clay-like material, and used it to mould abstract forms. Unmediated by the distancing of video camera and screen, they bear the marks of the artist’s kneading fingers and are redolent of sour milk. Described by Rachel Rits-Volloch as an ‘extrusion of her own bodily fluids, an inversion of herself from inside to outside, signed with her own fingerprints’(7), Cao has made the product of her own body into art. This is not unprecedented; in 1961 Piero Manzoni filled 90 cans with his own faeces. Each was numbered and labelled in Italian, English, French and German, identifying the contents as ‘”Artist’s Shit”, contents 30gr net freshly preserved, produced and tinned in May 1961’.(8) Thus, in a neat comment about the aesthetic judgement and intellectual acuity of the artworld, the product of the artist’s body became a commodity.

Cao Yu’s work is quite different, however, and arguably more interesting. Although she says, very emphatically, that she is not a feminist,(9) ‘Fountain’ and ‘Artist Manufacturing’ align more readily with works by feminist artists who challenged taboos around menstruation, pregnancy and birth and refused to hide the realities of the female body – its inconvenient leakiness, as well as its sexual and maternal power. Carolee Schneeman’s 1975 ‘Interior Scroll’, a performance in which she drew a long, narrow scroll of paper from her vagina and read aloud from it comes to mind.(10) So, too, do the performance works of Patty Chang, such as‘Melons’ (1998) in which she wears a large bra with the cups filled with cantaloupes that resemble prosthetic breasts. Chang slices through bra and melons with a sharp knife and scoops out the flesh with her hand, enacting an imaginary ritual at the death of her aunt from breast cancer. Chang also used her own breastmilk in ‘Letdown (Milk)’ (2017), photographs of the discarded milk she had expressed into cups and any other available receptacles as she documented an arduous journey through Uzbekistan. The double meaning of her title references both the physical sensation when milk begins to flow, prompted by the sucking of the infant on the nipple, and an emotional state of disappointment.(11)

Single channel HD video (colour, silent), 9′

edition of 6 + 2 AP.

Image courtesy the artist and Galerie Urs Meile

Like Chang’s, Cao Yu’s work explores the push and pull of apparent binaries: private and public, beauty and revulsion, tension and release, pleasure and pain, doubt and certainty. Socially constructed binaries also interest her; much of her work challenges gendered cultural expectations. ‘The Labourer’ (2017), for example, a video once again shot with dramatic contrasts of light and shadow, shows only a pair of pale legs standing on a pile of white flour. It takes a moment to realise that the yellowish liquid flowing down her legs to moisten the flour, which she kneads into dough with her feet, is the artist’s urine. This nonsensical, improbable ‘labour’ produces nothing at all. ‘The Labourer’ might be read as a satire on the making of art in a world that sees little value in the activity. However, Cao Yu’s intention was to confound orthodoxies of femininity by representing herself urinating while standing. The juxtaposition of aesthetic beauty – her gleaming legs emerging from the darkness and merging with the whiteness of the flour – with the absurdity of her actions prompts us to examine our deepest responses, whether of fascination or disgust.

Image courtesy the artist and Galerie Urs Meile

Image courtesy the artist and Galerie Urs Meile

This theme was further emphasised in Cao’s two solo exhibitions, ‘I Have an Hourglass Waist’ at Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing (2017) and ‘Femme Fatale’ at Galerie Urs Meile, Lucerne (2019). She approached each exhibition as a spatial and temporal installation, deliberating every aspect of how visitors would encounter her work. The aim was to unsettle and surprise. The opening salvo in this campaign began at the entrance of the gallery. For both exhibitions, the door handle was covered with Vaseline – a performative, experiential ‘work’ entitled ‘Perplexing Romance’ (2019) which included a gallery attendant stationed ready with a stack of tissues bearing the artist’s signature. The disconcerting stickiness of opening the door presaged further discomfiting experiences inside. In the washrooms, a soundscape entitled ‘The Flesh Flavour’ (2017) amplified noises of chewing, sexual intercourse and ambiguous clapping or smacking into different parts of the room. On the gallery floor, filling the entryway between two rooms, so that visitors had no choice but to walk on it, an undulating textile installation turned out upon closer inspection to be a pile of black bras stitched together to form a surreal groundcover.

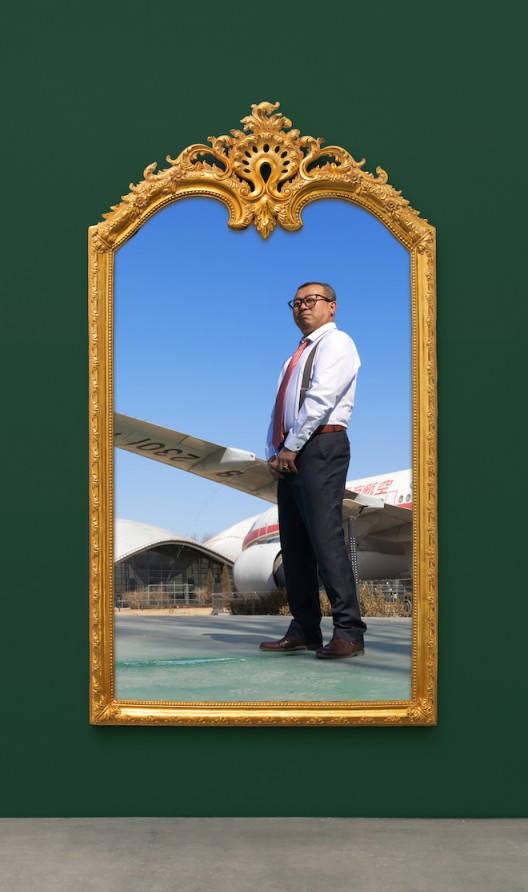

The large-scale photographs from which the title of the Lucerne exhibition was derived amplify Cao’s challenge to gendered expectations. Three life-sized photographs of men are hung in elaborately carved, gold Baroque frames reminiscent of those surrounding grandiose royal portraits. But the subjects of these works are far from aristocratic; they are ordinary men caught in the act of public urination. One is a corporate power-player peeing beside a plane, one a white-collar worker silhouetted against city buildings at dusk, while the third, a thuggish character in a red jacket, seems to have just realised that his antisocial act has been caught on camera. The artist lay in wait to photograph these unsuspecting men. It raises questions – is this an invasion of their privacy? Can it be, when they are engaged in such exhibitionism? Cao Yu says:

The figures I captured were not the royalty or nobles we often see in classical oil paintings; they were ordinary people from our lives […] they are the men we see every day who are peeing in different geographical settings. Ironically, some of them presented the same proud temperament as those of the emperors and nobles in classical oil paintings. They regard themselves as superior and like to be looked up to by others even when they are peeing. Some of them used a way of swearing or silent acquiescence to protect themselves and then fled quickly. Without exception they were swallowed up by these luxury frames with a golden glow. And they were stuck in these external frames forever, awkwardly.

Is Cao Yu the ‘femme fatale’ of the title? Certainly, with these unflattering images she removes any power these men might possess, rendering them as vulnerable and absurd creatures. Their final presence in the gallery is the result of some intense negotiating after the fact between each man and the artist (who reveals that she was protected from their anger by a few ‘uniformed bodyguards’). We can assume there were other instances where the negotiations were unsuccessful.

Self Portrait

In addition to Cao’s preoccupation with the body and its functions, and her interest in creating provocations that rupture gendered expectations and boundaries, she examines the nature of the artist and the materiality of artistic practice. At its most literal, she presents her official identity card as a deadpan self-portrait, blown up to a monstrous scale more than two meters wide, entitled ‘The Female Artist’(2017). The artist’s labour is revealed in the ‘Canvas’ series (2013 – ongoing) in which Cao laboriously traces the lines made by the warp and weft of the canvas with a marker pen. The resulting works appear delicate and ethereal, yet they are also an acknowledgement of the tactile nature of the fabric and the exacting physical work of their production.

Similarly, in the ‘Mother’ series white canvases are slashed to create openings that have been roughly sutured. The unprimed raw linen of the reverse has been pulled through these partly stitched slits from the back to the front and turned inside out. In ‘Mother No. 4’(2016) a plait of raw canvas hangs down like an umbilical cord. Again, Cao Yu creates a dialogue with art history while making work that is rooted in her own experiences. Referencing the ‘Cut’ paintings made by Lucio Fontana between 1958 and 1968 (12), the ‘Mother’ series symbolises the agonising passage of the child from the womb, that extraordinary moment when the infant’s head crowns and what has been internal becomes external. Like Fontana’s, Cao’s works blur distinctions between two and three dimensions, between destruction and creation.

Single channel video (colour, sound) 3′

edition of 6 + 2 AP.

Image courtesy the artist and Galerie Urs Meile

‘I Have’(2017), a video shown in both solo exhibitions, is perhaps the most subversive of Cao Yu’s works to date. The artist’s head and shoulders are brightly lit against her characteristic dark background. Gazing at the camera she begins to speak, as if directly to the viewer: ‘I have an envy-inducing figure… I have an hourglass waist… I have a husband who dotes on me… I have a ten-carat diamond ring…’ This boastful narration moves from the artist’s appearance, her enviable marriage and her child-prodigy son to some specifically Chinese aspirations: ‘I have a car with Beijing plates … I have a Beijing hukou.’ Then we arrive at the real point of the work: ‘I have an art history calibre work… I will be one of China’s most representative artists… I have everything an artist has or could ever want…’ It is unnerving to hear a woman bragging so shamelessly, although today we see this reclamation of (often sexual) empowerment from female hip hop stars such as Nicki Minaj and Cardi B. It contradicts everything that women are taught to be – or at least to seem to be. Cao has described her boasting as an act of ‘self-consolation’.(13) I Have is perhaps a form of ‘whistling in the dark’ to keep the monsters of self-doubt and fear away, but it is also a refusal to perform false modesty. Cao dislikes how people seek out weakness in others, how feeling pity serves ‘to protect their fragile glass hearts.’

Image courtesy the artist and Galerie Urs Meile

Each work in Cao Yu’s impressively coherent oeuvre reveals a little more about her ideas and intentions, like the sequencing of a narrative. The World is Like This for Now (2017) consists of a single strand of the artist’s hair (a material used in a number of works) that connects two roughly hewn blocks of marble. The tensile strength of a single hair is said to be stronger than steel, but it seems so fragile compared to solid stone. Does this paradox of apparent frailty and actual strength represent Cao Yu herself, a young female artist navigating the global art ecology? Cao agreed, citing ‘The Journey to the West’ in her response:

A single hair is the most vulnerable material of the human body. It is so tiny that it is barely visible, so much so, that it is even hard to be found in the exhibition hall. But this lonely long hair will swing slightly with viewers’ breaths when they are close to it. It appears free, but it is just like the Monkey King being pressed under the foot of Wuxing mountain by Buddha Tathagata […] The hard and cold stone is just what we face during the oppression and suffering around us at all times! But without them, there would be no manifestation of us. This is a temporary balance.

This ‘temporary balance’– uncomfortable and unstable yet also exciting – is precisely what underpins Cao Yu’s work.

56 x 46 x 36 cm.

Image courtesy the artist and Galerie Urs Meile

About the artist

Cao Yu 曹雨(b.1988, Liaoning) studied in the Sculpture Department of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing, graduating with a BFA in 2011 and an MFA in 2016. Since graduation her work has been shown in China, Korea, the United States, Australia, Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Solo exhibitions include ‘I Have an Hourglass Waist’, Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing (2017) and ‘Femme Fatale’, Galerie Urs Meile, Lucerne, Switzerland (2019). Awards include Best Young Artist of the Year·The 12th AAC Award of Art China (2018); named China Art Power100 (2018) and shortlisted for the Chinese Contemporary Art Award (CCAA); Nomination, the French Opline Prize(2019) ; Nomination, French Yishu 8· Chinese Young Artist Award(2017). Cao Yu was also selected into Gen. T China’s Top 100 New Pioneer (2020). Cao Yu lives and works in Beijing.

Notes

1. Zhan Wang, perhaps best known for his polished steel ‘scholar rocks’, is represented by Long March Space in Beijing. See the gallery website for examples of his work, a biography and other information. Available at http://www.longmarchspace.com/artists/zhan-wang-2/ [accessed 26.6.20]

2. The author interviewed Cao Yu via WeChat and email over a period of several weeks in May and June 2020. Cao Yu responded in both English and Chinese. All quotes from the artist are excerpted from this interview unless otherwise acknowledged. They have been lightly edited.

3. Discussed in He Chengyao’s interview with the author, conducted in Beijing in December 2014, and subsequently included in ‘Half the Sky: Conversations with Women Artists in China’. Piper Press, Sydney (2016)

4. See Sasha Su-Ling Welland’s account of these events in ‘Opening the Great Wall’ in ‘Pain in Soul: Performance Art and Video Works by He Chengyao’, transl. Mao Weidong. Shanghai Zendai Museum of Modern Art p.59 (2007)

5. Excerpted from He Chengyao’s interview with the author, conducted in Beijing in December 2014.

6. All quotes from Cao Yu are excerpted from her interview with the author unless otherwise acknowledged.

7. Rachel Rits-Volloch, in her essay ‘Portrait of the Artist with an Hourglass Waist’ for the exhibition ‘I Have an Hourglass Waist’ at Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing, 4.11.2017 – 23.2.2018

8. See the Tate information about this work, available at

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/manzoni-artists-shit-t07667 [accessed 17.6.2020]

9. There is an interesting history of the fluxing embrace and disavowal of Euro-American feminist theory in post-Mao China. And, of course, China has its own distinct, long feminist history dating to the late Qing and Republican periods. The work of scholar Min Dongchao reveals all the pitfalls and slippages of meaning as feminist theory was translated into Chinese in the late twentieth century. In terms of feminist art, the recent work of Julia Andrews, Peggy Wang, Phyllis Teo, Shuqin Cui, Monica Merlin and Sasha Su-Ling Welland addresses the ambivalence so often expressed by artists. Shuqin Cui argues that, despite the pioneering work of feminist critics and curators such as Liao Wen and Xu Hong, ‘Few Chinese women artists would welcome the label of feminist art or categorize their work as feminist art even if the feminist dimensions of their work were clearly evident.’ See, for example, Shuqin Cui, 2020. Introduction: Why (En)gender Women’s Art?. positions asia critique, 28(1), pp. 1-18.

10.See the Tate information about this work, available at

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/schneemann-interior-scroll-p13282 [accessed 17.6.2020]

11. See Patty Chang’s website for more information about Letdown (Milk) and other works. Available at

http://www.pattychang.com/#/letdown-milk/ [accessed 24.6.20]

12.. Tate information about Fontana’s ‘Cut’ works, available at https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/fontana-spatial-concept-waiting-t00694 [accessed 25.6.20]

13. See ‘Cao Yu: In the Name of the Body. Interview conducted between Tan Ying (London) and Cao Yu (Beijing) in November, 2017’ available at

https://www.galerieursmeile.com/application/files/8115/6353/6472/CY_Interview_2017_E.pdf [accessed 26.6.20]

Cao Yu – The Labourer 2017 excerpt from Galerie Urs Meile on Vimeo.