by Nguyen Anh Tuan

THINH – Đào Châu Hải

Manzi Art Space (14 Phan Huy Ích, Nguyễn Trung Trực, Ba Đình, Hà Nội) January 2021

Translated by Tran Ngan Ha

Publication was made possible with the support of the Nguyen Art Foundation

Les vrais paradis sont les paradis qu’on a perdus. (The only true paradise is paradise lost’) – Marcel Proust

As we enter the third decade of the 21st century, Vietnamese sculpture seems to be gradually losing its place in the living spaces and the flow of creative thinking. Just over 10 years ago (2010s), sculpture, then full of inspiration and often present in art news, was introducing a generation of new faces which promised a novel visual language.However today, it seems to have turned into disappointment when, apart from being heavy physical shapes, sculpture works often do not create any significant concepts or aesthetic perceptions. From a high-level perspective, from being an art form with a normative theory system of three-dimensional shaping, of specific technique and language, sculpture has gradually become a merely form of expression, a material and a ‘medium’ rather than a distinct sensory and aesthetic world. It slips out (or is pushed to the borders) of the flow of thinking – as sculptors no longer come up with their own aesthetic philosophy about how they form the shapes, equip them with a capacity to interact with different spaces, diverse contexts, and respond to living spaces that appear and disappear every day. When the present life is no longer isolated islands or kingdoms with standard models of distinct social and physical forms, sculpture requires changes in the artistic philosophy to interpret different aesthetic approaches, or should even guide human perception, but it seems to stand still or go in the opposite direction. Increasingly exhausted and no longer able to find life-engaging concepts, a visual language that is increasingly poor, unable to connect or lacking the ability to occupy real spaces, gradually losing its audiences, sculpture has become either “salonized” in furniture, or a superficial decoration of an outdoor space with a rigid and pragmatic spirit outside the aesthetic.

Dao Chau Hai (b. 1956) belongs to the last generation of sculptors pursuing a pure sculptural language and conception and who have the desire to change humanity – idealizing living spaces through art. Starting with his ’Cubist’ sculptures in the 1990s, since the 2000s there have been many changes in his perception and spirit regardingsculpture where he was searching for and incorporating his art objects into a variety of topographic and spatial contexts, from smaller to larger scales. The move from natural materials to metals around 2009-2010 continues to give his sculpture new forms and languages, not only within the context in which they are created, with the spaces to which they are directed, but also in their efforts to capture and shape the spirit of the era into a specific visual form. The ideology of the industrial age mixed with memories of the past, the sensitivity to the mechanical, the metallic with the non-metallic crafts, the pursuit of a three-dimensional oppressive body language through monumental art shapes, searching for ideal forms in the ideal space, radicalizing the language of shapes and engineering within the constraints of technology, et cetera, such complex and contradictory thoughts appear in the sculptures of Dao Chau Hai, and which are both a driving force and a hindrance to the artist himself.

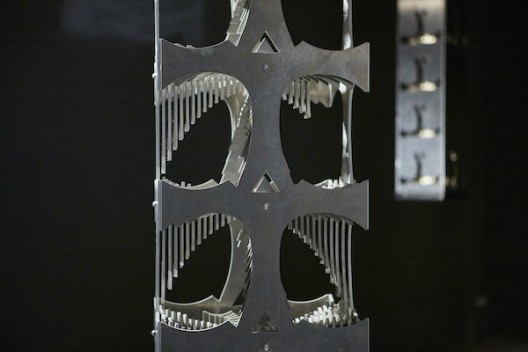

THINH, the latest series of work, starts out as an independent sculpture but then opens up Dao Chau Hai’s complex and diverse onsite interconnections. He starts with a simplified figure of a bird drawn on a flat metal surface. The shape is then hollows out using laser cutting techniques, and duplicated on the metal sheet vertically and horizontally. Splitting that flat surface into vertical rectangles and arranging on a square ground, then inserting small squares into larger square cylinders, Dao Chau Hai builds up a series of standing cylinders with multiple layers, alternating hollow and solid. Fragments cut from flat metal surfaces are also used, radially laminated and stacked to form a solid pylon – solid cube of hollow cylinders. The metal plates of the hollow sections are also not discarded; they are considered other components of the work, intended to be incorporated into specific spaces or terrain. The idea of using both solid-hollow cubes, the cold sharpness of metal and mechanical precision are fully exploited in this sculpture, creating a multidirectional visual reception and opportunities to enter various spatial structures which can be combined in different ways with architecture.

When a three-dimensional sculpture is flattened, it almost approaches the visual language of graphic art and requires comprehensively different directions of ‘behavior’ in terms of concepts, techniques, and aesthetics. The artist did not really make a sudden change in artistic style, but had experimented previously, such as his installation in the exhibition “Uninvolved & East Sea Ballad” at Viet Art Center, Hanoi, at the end of 2010 (a dualexhibition with painter Ly Truc Son). Dao used thin jagged steel plates to form the shapes of ocean waves, laying them on the floor and standing against the wall to create a fierce space filled with of the sensation of violence. Although they are dissipated in a large space without a coherent connection between single parts, and lean too much towards ‘description/narration’ and have no specialized way of processing the blocks’ interior, this is still an experiment and also a transformation in the perception of his structure of sculpture by decomposing the solid block into layered flat metal plates with space left in between. This technical process becomes an artistic approach when it comes to solving the ‘solidity-heaviness’ of the shape, emptying and reducing its weight, making it look more elegant. At the same time, the visually heavy effect of the metal material is retained, the layers stacking up one on another, creating a weight for the forms and a visual impression of the work.

With THINH, Dai reuses this approach with a greater degree of control in both artistic conception and technical precision. Plates of metal are either flat or laminated or separated into independent sheets. Hollow shapes created by chiseling on flat surfaces become the main driver of vision and determine aesthetic effectiveness. At this point, the void/empty space becomes organic and the main subject of the sculpture. Not only do they ‘take away’ the heavy feel of the material and the coldness of the metal, they also solve the overall visual riddle and detail of the work. They guide the viewer’s gaze to weave in and out of the block, exposing the structure and the physical depth of the block’s interior. At the same time, they are the doorways to connect the sculptural body with the architectural interior-exterior landscape and the environment. The work integrates more into the physical context and evokes a lot of interest in viewers because of that ‘openness’.

One advantage of choosing a reflective metal for this sculptural series (aluminum alloy) lies in the properties of that material. Not only is it responsive to light, the surface also reflects many passive and indirect light beams, without an external light source. This sculpture can be placed in a variety of architectural and lighting contexts, from outside to the typical white-cube gallery, in an artificial light hall, or even in a dim lighting spaces. In a dark space, the light on the contours of sculpture makes up the visual form of the subject and that’s where aesthetics reveal itself. The shape becomes fragile, even ‘invisible ‘, and the empty/void spaces become the solid block/subject of the work. When the light changes through time, from day to night, or by the movement of things in front of the work, by the surrounding natural and man-made environment, the visual aesthetic changes accordingly and is not constrained by traditional art disciplines. Diverse adaptations to the environment and scenery, time and weather help the work have a more ‘sustainable’ aesthetic, quickly catching up with the movements of thoughts and habits that always want to renew and accelerate the movement of contemporary life.

Explaining the concept through the title is seldom a strength of artists in general, but with the title ‘THINH’, it seems that Dao Chau Hai has had a satisfactory choice. THINH is part of the word ‘thinh khong’, which designates an empty, silent, nothingness state. Thinh in Vietnamese is pronounced close to the word ‘thing’ in English which means object, or ‘think’ which means thinking, reflecting. During domestic and international trips, the artist has had many opportunities to witness or listen to stories of people drifting, in exile or disappearing following the changes in history, the disintegration of communities and cultures, the rotation of natural and social status. From thinking about the existences of individuals and groups through the transformation of time, Dao Chau Hai approaches the topic with a complex sculpture series of various parts, layers, fragmentations and concentrations, in order to express different states that exist in endless emptiness. Perhaps this idea is more or less influenced by the Eastern Buddhist spirit ‘all things are empty of intrinsic existence and nature’ when it comes to seeing that all matters come from nothing and will return to nothing.

The change in the visual language of sculpture reveals the development of Dai’s thinking process and his researching/reflecting/experimenting capacity, and his artistic philosophy. In his early-staged Cubist forms, Dao Chau Hai was interested in the distortion of the sculpture in three-dimensional aspects, creating an internal ‘force’ inside the rotating cube, thereby affecting the viewers’ vision and emotions. At the same time, he explored the hollowness of sculpture when studying bamboo weaving techniques, inspired by the craftsmanship and the appearance of traditionalhandicraft with their own lyrical and aesthetic characteristics. Then he raised questions about the meaning of the shape in relation to the material and where the connections with the past in matter and identity lie. The next turn was employing the theatrical impression of the massiveness of the monumental art in three-dimensional space, its connection to specific space and context, a sense of industrial life, which certainly was influenced by the time when the artist undertook commissions of monumental statues forcommon architecture and public sculptures. The post-2000 works and showcases were constantly changing and experiencing a variety of scene modifications, demonstrating his artistic styles in dialogue with the space [site] at the physical, environmental or historical layer, following practices of Land art or Environmental art. Influence by industrial life, his excitement using the metal material, together with its technical system and visual language, a distinct aesthetic philosophy attracted the artist and has been his main object for more than 10 years. Working with metal requires more rational thinking, and sculpture will then either tend to structuralize, or will tend towards working in a conceptual sense more than in a technical one, and gradually become a medium for new artistic forms such as Installation. Dao Chau Hai’s later works show that he tends towards structures in the connotation of sculpture but is still interested in how the works interact and control the space in particular exhibitions. Going from Cubism (distorting or analyzing ‘cubes’ [of space]) to Abstraction –– structuralizing and bringing visual structures into space, rotating and colliding with the news, behavior and cultural sensitivities, Dao Chau Hai’s art follows the gradual development of global sculpture, and partly touches on the common perceptions of contemporary aesthetics.

When modern life needs more various expressions in forms, or more diverse exploration at deep emotional levels, or engaging with social and community issues generally, art needs to respond. In the context of sculpture getting further from reality, this artistic practice of Dao Chau Hai has been consistent, demonstrating the limitations of and distance between the creative ideal and reality, when the artistic idea slips from the existing technical and technological infrastructure, the social context and the existing psychology of enjoyment. As a perfectionist, perhaps he is still seeking to build a pure spiritual space, where art defines the values of the physical and spiritual form of that place. But that paradise has never been and will not be for anyone, because the world we live in today is constantly divided and broken, where ideals and beliefs become illusions and delusions. Đào Châu Hải is a solitary wanderer in the endless exile of the mind, searching for a paradise that does not exist, something that mankind has lost since the dawn of time even though art cannot help being a salvation of the soul in a chaotic and devastated reality.

Nguyen Anh Tuan

Hanoi, Jan 2021

Translated by Tran Ngan Ha

All images courtesy the artist and Manzi Art Space