Over the past couple of years I have been a fairly lazy writer, alienating most editors I previously worked with, and as such, my cautious requests for press accreditation to this year’s Biennale were swiftly ignored. My appetite for art is not rich enough to pay for either a Gold Card, which for 250 Euros grants access to the main sites during the three opening days, and certainly not for a Platinum Card, costing double and offering a few other benefits and knickknacks. So though I’m not immune to the love we all share for this joyful circus, I nearly gave up on coming to Venice. Quite at the last minute though, a curator invited me to participate in a collateral event, and consequently I received my very own invitation. On top of that, a few days before arriving, the Randian people asked me to write something for them (probably because other writers called in sick or something) and that will pay for my accommodation. This year, to my dismay, I was not able to squat on anyone’s sofa, and actually had to rent a tiny apartment and share it with as many people as possible.

On my first morning in Venice, after a leisurely walk in Giudecca, a dear friend invites me for lunch at a restaurant called I Cacciatori (“The Hunters”). We sit along the bridge of the canal, on the other side of which we see the San Marco bell tower. I eat an astoundingly delicate charcoal-grilled octopus on a chickpea cream, while my friend eats rabbit with mushrooms. I drink white, he drinks red. We then order a cheese platter, which we nibble on, unrushed, drinking a different bottle, and, after a cup of coffee, we linger on our chairs for another hour or so. Our conversation indulges in Venice, on how life in it is so magically close to what it was 300 years ago, and on the marvels hiding behind the closed gates of its palaces. We try to enumerate the many kinds of seashells and crustaceans born and so finely cooked in the Lagoon. We tell each other of old amorous adventures in this wonderful city and of its endless, silent nights.

All of this I am writing to explain how justified I feel in not having been to “All the World’s Futures,” the main exhibition of the Biennale. You can read about it for sure in some other article anyway—I’ll do the same. I’ll also promise to learn how to pronounce correctly the name of its curator Okwui Enwezor, to make amends.

In the Giardini, the Canadian Pavilion stands out as a clever and well-conceived gimmick. It’s been built by the artist trio BLG and sits high above a scaffolding structure, just next to the British one, like a tree house in the garden of a mansion. Upon entering its first room, we see a reproduction of a Québécois dépanneur (basically, corner store) where the labels on the goods become blurrier and blurrier as one walks towards the exit behind the till; many must have lingered on the fine memories of being extremely intoxicated late at night and craving Doritos or Vanilla Coke—I certainly did, and my only complaint is that one cannot buy anything from the shop.

Venetians are notoriously rude to tourists, though tourists are their major source of income. The two main categories of scornful Venetians are bartenders who refuse to cut sandwiches in half for you, and pensioners who try to push you out of the vaporetto (water bus) while rushing to get a seat. Incidentally, it’s advisable not to fall in the canals of Venice; under the opaque surface of the water lie the corpses of all the drunkards who fell in from bridges and boats over the past five centuries, plus horrendous creatures of the deep, two soviet submarines, a spaceship, and all of the artworks from previous biennales, discarded in November.

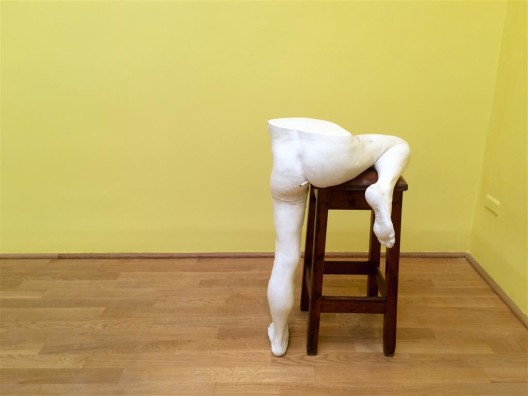

Sarah Lucas has painted the whole interior of the British Pavilion a bright yellow and populated it with white humanoid sculptures that push forward their genitalia and smoke cigarettes from their butts. As my flatmate puts it, the work and the artist seem to scream: “It’s sex! It’s rough, it’s dirty and it’s sex! Deal with it! Alright mate? Deal with it!” Okay, Sarah, we’re dealing with it; as a matter of fact, we are all quite comfortable with it, and there’s really no need to scream. But thank you, Sarah, for referencing in your introduction floating islandsas a source of inspiration for the Pavilion; it’s one of my favorite desserts. And my apologies, Sarah, for calling you by your first name as if we were friends, and being so condescending and patronizing—it really is an awful attitude.

I see a number of performances around town, including a woman sitting on a fake electric chair, another one climbing like a spider from a web of ropes, and yet another walking around naked with a rabbit mask. Except for the mesmerizing body of the latter, not much impresses me about any of these works to which we typically dedicate a single careless glance before running from one event to another, and which end up looking just like any other juggler or busker outside underground stations—though lacking the talent necessary to play the accordion or spin a yo-yo very fast.

Having said that, I really enjoy the spectacle of a Special Corps squad jumping out of a stealth speedboat in front of the main entrance of the Giardini. Six armed men martially line up in front of a bunch of passers-by, then burst out laughing and quickly form a human pyramid; moments later they’re back in their speedboat and they disappear along the canal as quickly as they had come. It’s “Machines of Loving Grace”, a performance choreographed by Harold de Bree and Mike Watson, and later someone shows me pictures of the squad being stopped and interrogated by the actual Italian Police.

Lounging with me and a few art-surfers at the end of a long day of explorations, a gallerist from the south of France tells me how she finds the whole of the Biennale to be rather depressingly self-referential. She says art should be made for people who are not strictly involved with its processes, and that it should be taken out of its designated spaces to populate the world it claims to be reflecting upon. While I couldn’t agree more with her; I can’t avoid thinking that if a gallerist has reached this conclusion, either we are seriously nearing a dramatic climax in the entropic evolution of contemporary art, or she resents that none of the artists she represents have been selected to be part of the show.

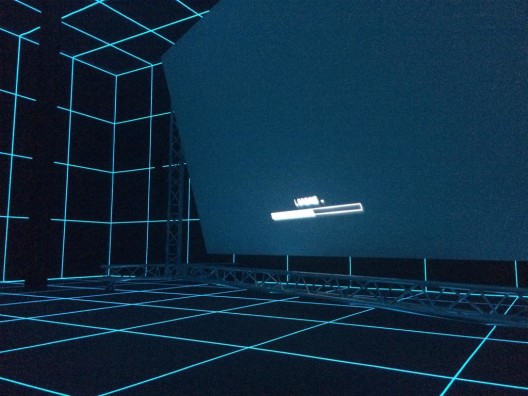

I cannot add anything useful to what you have most certainly already read or heard about Hito Steyerl’s work in the lower floor of the German Pavilion, but I must urge you to see it a couple of times at least, sitting on the armchairs and enjoying the plasticky smell of the room. It’s just that good.

Let me recommend where to take a break when you’re starting to run out of steam but can’t yet afford to leave the Giardini or the Arsenale without looking uneducated.

First, aim straight for the French Pavilion, where you can enjoy lying on your back and stare blankly at Céleste Boursier-Mougenot’s tree, which moves slowly around the room, while listening to ambient music. Wandering tree + trippy music? Bravo France for giving us such a reconciling work!

In the Arsenale, you have instead a fantastic halfway point in the Tuvalu Pavilion, where you can sit on benches along the scruffy walls of a room flooded with light from the large windows and steam rising from the pool in its middle. You would be excused for not knowing much about Tuvalu; it is, after all, a diminutive archipelago in the Pacific Ocean, with a population of only 12,000, It has become important though, as it symbolizes the damage we are gracefully delivering to our planet, and, within a few years from now, it will disappear under water due to global warming. Ironically, Tuvalu produces zero carbon emissions and even its delightful pavilion, designed by the Taiwanese artist Vincent Huang, will be fully recycled at the end of the Biennale, while information regarding it is distributed solely digitally, making it the first PaperSmart pavilion in Venice.

In Loulou’s pop up venue at the Bauer Hotel, two artists are giving a cocktail party to celebrate their recent wedding with a relatively intimate crowd (I don’t even know them or remember their names). There’s kitsch decor, artworks provided by swanky Gazelli Art House in London, people dressed as giraffes, and a cascade of Americano cocktails. Mix a bit of creativity and quite a lot of money, and you get the best party I went to in Venice.

Italian Pavilion: No

Chinese Pavilion: No

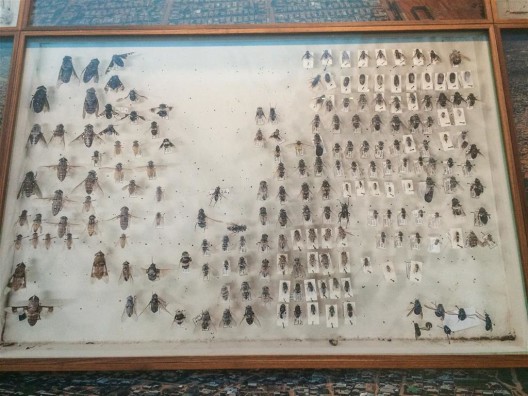

A large picture of all of the world’s species of bees scares the spritz out of me as I’m allergic to them; it obscures all the rest of the much-praised Belgian Pavilion.

On the other hand, I much enjoy the party organized for it on the same night; pizza, beer and techno music.

Hating the idea that Venetians only pay 1.30 Euros for a vaporetto ride while the rest of us are extorted an unbelievable 7 Euros, on my first day in town I don’t buy a single vaporetto ticket. I am clearly not the rebel I used to be though, and I am stressed so much by the thought of the controller catching me and dragging me to the city’s dungeons, that I am made impervious to the beauties of the lagoon and to the caresses of the sun. So I surrender and reluctantly buy a 2-day ticket for 30 Euros. Once I’m over having parted from my money, I actually become rather excited about my pass, and try to use the vaporetto to go anywhere. The euphoria subsides at the end of my last ride, when I realize I won’t be given the satisfaction of showing my pass to a controller.

The Japanese Pavilion, with its keys and red thread hanging from the ceiling, reminds me of an Indian restaurant in New York’s East Village, the ceiling of which is covered with plastic chilies and all sorts of trinkets. If you go there and it’s your birthday, or you pretend it’s your birthday, the waiters will switch off the lights, do a funny routine to some dance music, and bring you a scoop of ice cream with a candle on top.

Political Venice:

Protesters rallied at the Guggenheim Museum to denounce the employment of underpaid laborers in the Gulf, where the museum is building a new space.

Yellow umbrellas were opened during the inaugural speech at the Hong Kong Pavilion.

Ukrainian protesters invaded the Russian Pavilion wearing army uniforms with the label “On vacation.”

Under the Icelandic flag, the Swiss-born artist Christoph Büchel turned the thousand-year old church of Santa Maria della Misericordia into Venice’s very first mosque, causing quite a turmoil among the local population, but receiving much praise from the Muslim community, happy that they have a beautiful place for their Friday prayers within walking distance.

A famously unstable art PR giggles over her glass of prosecco, uncovering a row of minuscule, shiny front teeth, and rolling her eyes emphatically for a couple of seconds too long: “I don’t know why, but I still insist on trying to see some art around here.”

I meet Pamela Rosenkranz right in front of her work at the Swiss Pavilion, and I shake her hand to congratulate her. She seems a little awkward and shy, staring at my shoulders rather than at my face as I ask her a couple of questions about her work, a swimming pool filled to the brim with a bubbly pink liquid. She wears a dark blue trench coat and she moves quietly along the walls of the space during the very crowded opening reception. She looks as dreamy and potentially dangerous as her piece.

I am sitting with my dear friend at the far end of the St. Regis Hotel garden. We are taking a long break from circling around the vast swimming pool between the lounge tents, the two cocktail bars and the large stage where a busty girl in a skimpy dress is singing live versions of dance hits from the ’90s. A zealous waiter has found us in our outdoor living room and has brought over four different bottles of good wine to choose from. We have arranged in front of us a selection of delicacies we took from the buffet rooms (yes, rooms), and, as we chat, we feast on a simple yet tasty parmesan risotto, on caprese salad, on little sliders, on deep fried stuffed olives and on a platter of cold cuts. It’s 2 am and we are planning to explore the dessert area in about half an hour.

This must be the most opulent Pavilion party of the Biennale; Turkey has really outdone themselves. In this moment of relaxation though, our thought goes to Sarkis, the 77-year-old Armenian-born artist who’s representing Turkey this year. His conceptual practice is uncompromising and rigorous, and he has taken over a year and a half to develop his installation “Respiro”, which, beyond a rather pleasing surface of rainbow lights, mirrors and soothing music, contains layer upon layer of historical references, reflected not only in the imagery, but in the very choice of materials and proportions of the space. So strong is this piece, and so unassuming and subtle its political power, that the Turkish authorities have decided not to show up at the Pavilion—admittedly it must have been a difficult year for them, with this and the Golden Lion going to the Armenian Pavilion.

There is nothing subtle or unassuming about the party at the St. Regis; nothing that aims not to be ephemeral, nothing that would alert a politician. It is a strange divide that separates the two faces of Turkey in Venice, one that makes us feel rather uneasy. Yet, my friend and I agree (while sinking deep into the plushness of our armchairs) that it’s good to know that in a couple of hours, when we will have had enough of all this Ottoman magnificence, a taxi boat will take us back to town from this island, courtesy of Turkey.

As usual, going to the Biennale feels like a dream—one never gets used to the beauty of the city and the contrast of old and new. The art and the propositions made with it feel just like glimpses. I don’t believe anyone who claims to have been seriously able to digest much of it— especially those who have managed to see more than 20% of the show and the events in the first three or four days. On the plane back to London, fearing the forecast of bad weather at landing, I gently doze off, but the feeling is rather that of waking up from some delirium of my subconscious. A flight assistant hands me a cardboard box containing an icy chicken Caesar salad wrap.