Until the curator, critic and academic Roselee Goldberg founded Performa, a performance biennial in New York, in 2004, performance art was largely absent from large cultural institutions in the city such as museums and blue chip galleries. Staged in underground clubs and experimental spaces, the medium was looked upon as a relic of the past. Its heyday was the 1970s, when real estate in New York City was dirt cheap, and artist such as Jack Smith, Vito Acconci, Laurie Anderson, Mike Kelley, and Yvonne Rainer had the time, energy—and space—required for performance art to enter the larger cultural discourse, and assert itself as a viable means of visually expressing a body of knowledge. It perfectly complimented conceptualism, which needed forms to manifest ideas—the body being the cheapest, and readily available, form available to anyone willing to use it.

In “Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present,” a seminal essay Goldberg wrote in 1979 when she was a young academic studying the medium, she asserted that “whenever a certain school, be it Cubism, Minimalism, or conceptual art, seemed to have reached an impasse, artists have turned to performance as a way of breaking down categories and indicating new directions.” By the early 1980s, categories of what art could or should be had been thoroughly broken down, and attention turned once again to more traditional mediums such as painting and photography. The Pictures Generation, which included Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, and Barbara Kruger, came of age, and was followed by large, flashy art stars such as Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst, whose outrageously expensive work was more frequently discussed in terms of price than quality. By the early 2000s, performance as a visual medium had all but vanished from institutions.

“When I worked at the Whitney in the early aughts, performance in museums was largely a band that came and played on a Friday night,” recalled Adrienne Edwards, one of the curators of Performa 15, and a scholar of performance with a focus on artists of the African diaspora and the Global South, in a phone conversation with Randian. There was a sense of ennui in the art world—a feeling, reflected by the art markets, that art was only for the very rich, and that institutions catered to their tastes more than to the general public.

This changed in 2004, when Goldberg, who had continued her studies of performance art since the 1970s as a professor at New York University, decided to found the Performa Institute—a think tank that staged public programming around the topic of Performance. The idea to do so came in the wake of the successful staging by Goldberg of Iranian artist Shirin Neshat’s “Logic of the Birds”, a 2001 interdisciplinary performance that reflected on 12th-century Persian mysticism, and traveled with much critical acclaim to the Walker Art Institute in Minneapolis and Artangel in London after a successful 2002 debut at Lincoln Center in New York. The performance’s success coincided with a new interest in conceptual art made in the 1970s, as well as a shift in what the public wanted to see in museums. “I think museums began to reflect on what audiences wanted,” Edwards said of a renewed interest in performance art. “Institutions asked, ‘How can collectivity be expressed?’ And, ‘Where do people coalesce?’ They began to see that performance is a particularly viable vehicle for bringing audiences together.”

The viability of the medium was lent credence by Performa itself, which staged its first biennial, Performa 5, in 2005. Held at 20 venues throughout New York City, the program consisted of performances, exhibitions, symposia, and film screenings—all revolving around the subject of performance art—that was seen by over 25,000 people. In a globalized art world increasingly saturated with art fairs that people were more likely to compare to cattle auctions than exhibitions, given that they were held in enormous convention centers somehow made claustrophobic by mazes of tiny booths, Performa offered something different—an opportunity to see art in the flesh, made by artists who themselves pulsated with a life that audiences felt, and could participate in.

Performa 5 birthed a series of biennials that grew in scope, encompassing commissions by the festival’s curators, and encouraging participation from artists, curators, critics and institutions alike—thus far, there have been six iterations. Many of the world’s most exciting and prominent contemporary artists have participated including Elmgreen & Dragset, Simon Fujiwara, Ragnar Kjartansson, Mike Rottenberg and Jon Kessler have participated.

Responding to the festival’s popularity and critical success, major institutions began incorporating performance into their own programming. In New York alone, every major institution has incorporated performance into its regular programming. For its past two iterations, the Whitney has devoted an entire floor of its institution to a rotating series of performances and performance residencies during its Biennial. It also staged “Rituals of Rental Island,” which ran from October 2013–February 2014, and examined performance art made in New York between 1970–80 as a way of contextualizing the blossoming medium in the contemporary sphere. Major retrospectives have been given to Chris Burden, known for his extreme acts such as shooting himself as part of a performance, at the New Museum; and Marina Abramović, whose performance, “The Artist Is Present”—which involved the artist sitting and staring into the eyes of whomever wanted (or dared) to meet her gaze—at the Museum of Modern Art in 2010 which became an international phenomenon. “I truly do believe that Performa showed there were committed resources to performance, and that museums responded to this,” said Edwards. “That episodic, one-off events can bring a complexity and quality to other mediums.”

In its sixth iteration, Performa 15 revolved for the first time around a theme—the Renaissance. Firstly, the theme established a place for the festival, which took place this year from November 1–22, in the lineage of art history. The Renaissance was a period of intense cultural production during the 14th and 15th centuries in Europe that has had lasting reverberations on the world even five hundred years after it ended—perhaps we are living in such a period today, and performance art is a vital part of the reason for it, Performa 15 argues. But more than being a bombastic way of situating itself, the theme of the Renaissance offers a keystone for looking back over our cultural history, and uncovering what has been hidden about it. “Europe didn’t wake up one day and find itself in the Renaissance,” says Edwards. “It happened because of a series of major shifts that were the result of deep transmissions between Europe and the rest of the world, and most especially Asia and the Middle East.”

The Renaissance, Edwards argues, was an age of discovery. Along with trade routes through Asia, there were expeditions that led European explorers to the Americas and to Africa. They brought back artifacts, cultural objects, and other sorts of ephemera that informed what, throughout history, has been remembered as a deeply Eurocentric cultural blossoming. But just as is the case today, the European Renaissance in the 1500s would not have been possible had it not been for the influences and new ideas that flowed through the world via scholarship and trade routes from areas that continue to be ignored, although hopefully not for long, by art historians.

Such is the same made with any art today, only the information moves much faster, traveling along channels established by social media and the Internet. The theme of Performa thus is about, as Edwards says, “displacing the notion of a ‘time’ of a Renaissance.” It traces our obsession, as a connected society, with the “new,” which is an adjective that can be used to describe anything from the re-discovery of the Greek philosopher’s treatise on Geography during the Renaissance, to the uncovering of art made in the closed society after apartheid ended in 1994 in South Africa. If one could re-position the Renaissance any time, in any place, then what would one discover that would be revolutionary?

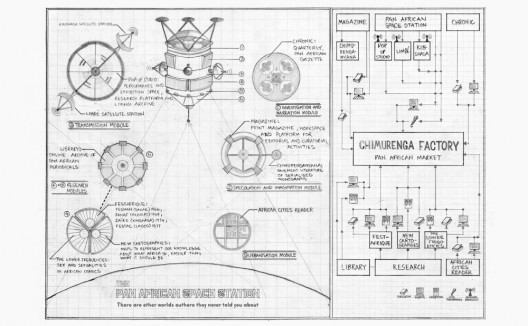

For her part, Edwards attempted to encourage such a discussion with “The Chimurenga Library”, which was staged by a Cape Town-based collective from November 11–15 at the Performa Hub, which was located at 47 Walker Street, a loft in Soho. Rather than trading goods, participants were encouraged to share ideas, poetry, music and their archival knowledge. Sitting on furniture designed by Mickalene Thomas, the participants in the event formed what Edwards called an “embodied library”—the burned books of ancient Alexandria made into flesh. Edwards also organized Babylon Brazil, a series of performances by Brazilian artists Jonathas de Andrade, Eleonora Fabião, and Laura Lima that highlighted the excitement of working with the medium of performance in a country such as Brazil, where the ethnicities of people are so varied, and the rich are so very deeply divided from the majority of the population. There, performance, with its ability to say so much without having to use too many materials, only willing participants, is making a profound impact from the streets to institutions.

Multiculturalism was a theme not only in Edward’s events, but at Performa 15 in general, where more than 30 artists from 12 countries around the world staged events. These included Robin Rhode (South Africa), Jesper Just (Denmark), Zheng Mahler (Hong Kong), Tania Bruguera (Cuba), Agatha Gothe-Snape (Australia), Oscar Murillo (Colombia), Francesco Vezzoli (Italy) and Erika Vogt (United States), to name just a few.

Most lauded of all the performances was Los Angeles-based Edgar Arceneauz’s “Until, Until, Until…”, also curated by Edwards, which was based on the black entertainer Ben Vereeen’s censored performance on the occasion of Ronald Reagan’s 1981 inaugural celebration. In the original, Vereen offered biting commentary on the history of segregation and racial stereotypes—the footage was deemed to be too inflammatory, so it was not televised. In his performance, Arceneauz recreates the original inaugural party. The juxtaposition of the past act, and the current moment in American history, in which we are dealing, yet again, with a history of racial segregation, and the silencing of its effects, that has yet to be eradicated, led “Until, Until, Until…”to win the prestigious Malcolm McLaren Award. Given to an artist deemed “young and bold,” the award came with a $10,000 cash prize, and was presented by Young Kim and Richard Hell, a founder of the punk scene and inspiration for the Sex Pistols. Past winners of the award include Ragnar Kjartansson and Ryan McNamara, whose “MEƎM: A STORY BALLET ABOUT THE INTERNET”, went on to be performed at venues around the world, including at Art Basel Miami Beach.

Other highlights included Vezzoli’s “Fortuna Desperata”, which featured David Hallberg, principal dancer for the Bolshoi Ballet and American Ballet Theatre, and was inspired by the first ballets performed at Italian Renaissance courts in the 15th century; Nina Beier’s “Anti-Ageing”, which was performed at the Swiss Institute in a quasi-domestic installation; art collective Zheng Mahler’s “New York Post- et Préfiguratif (Before and After New York)”, which drew parallels between today’s Hong Kong, and New York in the 1940s as described in the writings of Claude Lévi-Strauss; Murillo’s “Lucky Dip”, which featured a banner bearing the logo of a South African corn brand hung on the façade of the Customs House in downtown Manhattan, as well as a performer singing a Spanish ballad on the steps; and “House of Flying Boobs”, which uses a Richard Nixon quote about a visit to China (“At the breast of history I sucked and pissed”) to deconstruct cabaret in a post-feminist world.

Performa has established itself to the point where in New York, as November approaches, the art world begins to anticipate it. It makes an argument for its own existence by its popularity; but also for the existence of performance art not just as a medium to turn to when, as Goldberg once wrote, artists have exhausted all other possibilities. “It’s a mode that encompasses all forms,” says Edwards, meaning that performance can be painting, dance, music, film, photography, or really anything. “Together, they can express something entirely differently than if they were left by themselves.”