Put your headphones on—on high. Daft Punk’s “Get Lucky” would be fine to start with, but we need something harder. Much harder. Primal Scream or The Clash would be good—historical, raw, a thumping electronic mind injection. Now step onto the floor, and feel the hum. Welcome to Jim Lambie’s synesthesia.

Premiered at the Glasgow International biennial in 2008, “The Strokes” were designed to destroy the self-important colonnade of the grand salon of Glasgow’s Gallery of Modern Art. They succeeded. It was if Roy Lichtenstein had driven back-and-forth a thousand times between the neo-classical columns with a giant, perfect Pop Art brush tied to the back of the car, swooshing black and white paint “strokes” in a perfect Alhambra-esque pattern. And the name? New York band The Strokes called themselves that because of the sexual and guitar references. There’s something of both of these in Lambie’s floor-work, too, because it really is all about rhythm and music and losing yourself in your own head.

It is also about paint strokes. Only there’s no paint here. This is vinyl tape, applied incredibly precisely to the floor (note: “vinyl”, a cipher for LPs and “tape”, for music tapes). It is not permanent—at the end of the show all the tape is ripped up and thrown away. It is also site-specific. Lambie plans these installations minutely, obsessively. The patterns are determined by the space they occupy. In early multi-colored works such as “Zobop” (1999), the tape fastidiously echoes the wall and colonnade plan of the Duveen Galleries in Tate Britain, London, turning the staid hall into a zinging electric dance floor just begging for John Travolta to put his white suit back on. Lambie himself has said:

“For me something like ‘Zobop’, the floor piece, it is creating so many edges that they all dissolve. Is the room expanding or contracting? … Covering an object somehow evaporates the hard edge off the thing, and pulls you towards more of a dreamscape.”

Lambie is making the room thrum with the resonance of its own architectural structure, amplified by vibrating color, and the elemental experience involved in walking on-to and in-to a space. And he is making you pause and remark your presence in that space, and the action and experience of moving through it—to see more precisely, to hear more acutely, to be more aware of your existence in a certain place, at a certain time—the zero-gravity of a dance-club beat, the panic-joy hyperventilation, the light on your eyes, the sound in your head.

Glasgow

Lambie (b. 1964) was never part of the infamous YBA brat pack, which always tended to be more London-focused. Lambie was born and grew up in Glasgow, a city renowned for being the toughest in Britain but also Scotland’s creative maelstrom. In the 1980s, Lambie was already getting into the Glasgow art scene, but he was just as involved with its music scene. He even shared a flat with John “Joogs” St. Martin, a then-member of Primal Scream, and he was himself a member of the proto-Teenage Fanclub band, The Boy Hairdressers (he played the Xylophone). Art won out though, and from 1990–94 he attended The Glasgow School of Art. Perhaps Lambie’s knack for infiltrating serious spaces was helped by the fact that Charles Rennie Mackintosh, the leading Arts & Crafts movement architect, designed the Glasgow School; but it was certainly a crucible of major artistic talent: among others, Douglas Gordon (1984–88, winner of the Turner Prize 1996), David Shrigley (1988–91, nominated for the Turner Prize this year), and Richard Wright (1993–95, winner of the Turner Prize 2009) were all students. Lambie was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2005.

Op Art

These floors—there have been quite a few now—are responsible for putting fun into Op Art—not “back into” though, because it wasn’t there to begin with. Op Art protagonists including Bridget Riley (b. 1931) and Victor Vasarely, like their Minimalist cousins, earnestly worked to establish the intellectual bona fides of their cause, so no smiling was allowed. Maybe Bauhaus color-tsar, Josef Albers, and his vast magnum opus tome, the Interaction of Color (1963) are also to blame, maybe just an unwelcoming public. Either way, unfortunately, it meant Op Art had a tendency to stultifying self-importance (just ask Lambie’s contemporary Tobias Rehberger, who is being sued by Riley for plagiarizing her work by inverting it and blowing it up as a permanent installation in the reading room of the Berlin State Library—the work looks like a checkered open book). No smiling? Jim fixed that.

China

Pearl Lam’s eponymous gallery in Hong Kong traces its roots back to 1993 when it opened as Contrasts Gallery, holding pop-up exhibitions around Shanghai before obtaining a permanent home in 2005 near the Bund. Since its re-launch as Pearl Lam Galleries, there has been added drive and zip to the program. It has a redoubled focus on China’s modernist and abstract painters (Zhu Jinshi, Su Xiaobai and Li Xiaojing) and, at the same time, a desire to bring Chinese and international abstract art into conversation (Jason Martin exhibited at the Hong Kong gallery in 2013). One of the interesting things about the gallery’s choice of Jim Lambie is not only the connection with (color) abstraction but also the element of design in his work, most apparent in the floor installations.

The Flowers of Romance

This show was a small but perfect retrospective of Lambie’s work, including a blue and white version of “The Strokes”. The all-over floor work has the effect of uniting the different pieces in a modernist labyrinth. It includes the totemic “Psychedelic Soul Stick 75”, the latest iteration in an ongoing series of “self-portraits” (one for each solo show) that involve tying ordinary but personal objects—such as odd socks and cigarette packets—to a bamboo cane, all of which is then bound with colored thread. It conjures images of tribal fetishism and magic, but its name leads us to think of music and percussion (Lambie is still a musician and DJ). In the 2013 show, it commanded a corner to itself—corners being one of modernist iconography’s ritual places—waiting to be picked up and twirled and hit and used as a microphone—egotistical, free, sexual, or whatever you like, really. Or just Jim, leaning against the wall.

Corners appeared again, actually incorporated into two recent aluminum-sheet wall-works, “Metal Box (Istanbul)” (2013) and “Metal Box (Hyacinth Orchid)” (2013). Lambie can be anti-intellectual, or rather an anti-snob. He uses and adapts ordinary things, whether vinyl-tape, old records, odd socks, or simple aluminum sheeting. In “Metal Box (Istanbul)”, seven colored square sheets, one on top of the other, are folded symmetrically at the corners as if a child had been playing with colored paper at school. It is an origami homage to the square, to the first square modernist, the Russian Suprematist, Malevich, and undoubtedly to Albers too. And its metal-folding recalls somehow, too, the battered sculptures of John Chamberlain, only Lambie’s are all shiny and new, and Jeff Koons’s shiny perfectionism. I cannot help but wonder if Lambie isn’t having a bit of a laugh at the expense of both these artists. “Metal Box (Hyacinth Orchid)” takes these games a step further, with a bank of two rows of three squares, but with the final sheet mirror polished, creating a kaleidoscopic eye-crash, twisting the room into a joker’s hall of mirrors. Lambie undercuts pomposity deliciously—surely something that nags at Angela de la Cruz, whose sculptural medtiations on painting and its supports got her nominated for the Turner too. Oh well.

On the sea of “Paint Strokes” float half-submerged concrete cubes with old record albums embedded in them—“Sonic Reducer” series (2008): these are not so much islands, but flotsam and jetsam for you to cling to as you flounder in Lambie’s Jackson Pollock “in-the-painting” experience.

The jokes keep coming. Lambie’s own version of a Damian Hirst spin painting is called “Vortex (Into the Void)” (2013), simultaneously taking a poke at Hirst, Vasarely and Riley (compare Riley’s “Blaze 1” from 1962). Appropriately, Lambie’s critique is headache inducing. Meanwhile, there were canvases crimped and furrowed by floating lines of safety pins—only these Punk pins are not so much about safety but transgression and menace, a threat to the supposedly sacred painting surface like body piercings were by UK punks in the 1970s, only now it’s no longer transgressive at all, just fashion.

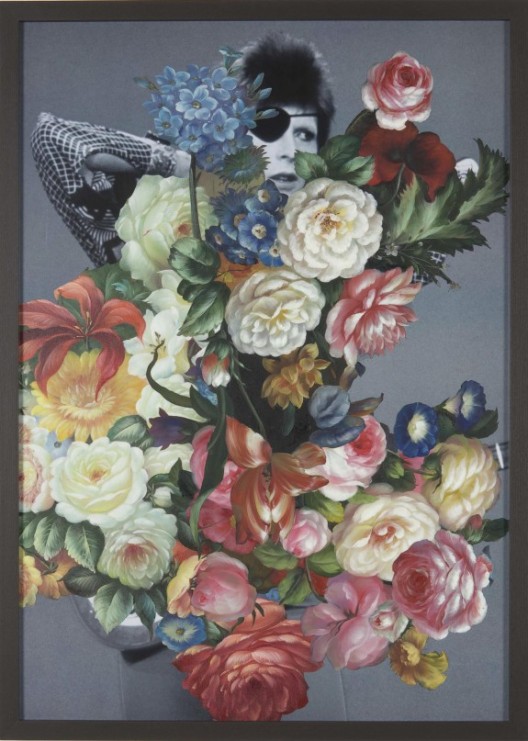

Jim Lambie did the cover for Primal Scream’s album “More Light”. In the middle is a black and white photo of lead singer Bobby Gillespie, holding his hands to his head like insect antennae, and surrounded by all sorts of collaged flowers. The cover is from a series, several of which were also on display in Hong Kong. The music, the old photos, are instances in Lambie’s personal history, the music that marked his development as an artist, musical and visual. It is a deliberate drop in tone from the fizzing, boggling visuals of Lambie’s floor-works and sculptures. He returned us to the real world, the quiet after the concert, the moment the headphones are removed. And we hear the silence.

Following “The Flowers of Romance” and subsequent exhibitions in Edinburgh, London and Tokyo, Lambie’s work is currently on show in Sydney at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery: “Zero Concerto“