“There is a place with four suns in the sky – red, white, blue and yellow”

Edouard Malingue Gallery (Sixth Floor, 33 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong), Aug 24 – Sept 16, 2016

Wang Zhibo is a fascinating painter, not least for her ability to disrupt the most banal of compositions to trigger both irony and unease. Her last solo exhibition, “Standing Waves”, at Edouard Malingue in 2013, centered around uninhabited artificial landscapes—Western artefacts dumped in the middle of Chinese settings that remind one of China’s so-called “ghost cities”.

While the artist’s latest exhibition, “There is a place with four suns in the sky—red, white, blue and yellow” features a similar amalgamation of the natural and artificial, it diverges from Wang’s previous works in its blurring of the line between human and non-human. In “We leave that to the people who wear them” (2015), a maternal figure appears to be nursing her young child. But the mother’s head is nowhere to be seen; instead, a row of bones adorn this figure’s neck. A broken limb lies desolately at the bottom left corner. Yet it appears less as if the scene depicts a grisly crime than it does merely a pile of bones and flesh someone that has assembled. The irony of the title, which takes after a famous Rolex advertising slogan, “A Rolex Will Never Change the World. We leave that to the people who wear them”, is not lost: how much agency do the figures in the painting have, if any?

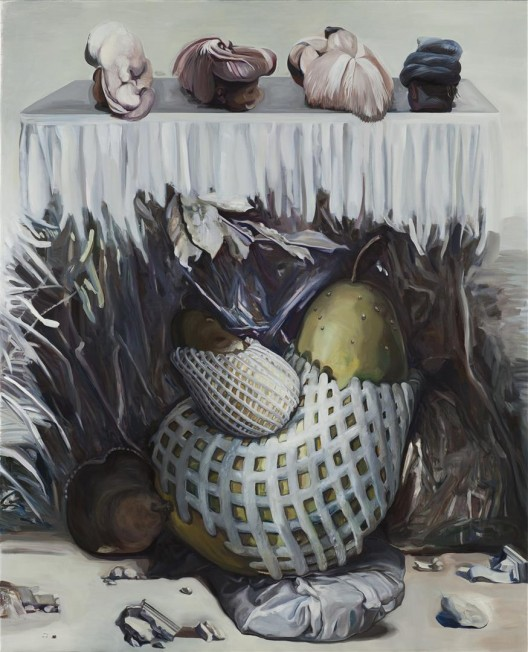

The parent-child relationship is humorously reprised as two pears in “Swaddling” (2016), with the bigger pear appearing to hold the smaller one in her (his?) bosom. This might lead one to reflect further on the different approaches we take to “subject” and “object”. It’s an idea that was previously laid out in “Dancing is better” (2015) which features a series of figures dancing, posing and in other attitudes in a circle. Aesthetically, the poise and muscular lines here recall classical Greek sculpture. A few yogis, arched backs and all, are also part of the painting. Disparate in context and time, the only thing linking the two assemblages is a sense of beauty attached to the human frame.

Reading like a 17th-century Flemish still-life, “Summer Kitchen” (2016) is suffused with all the right elements—a roasted chicken takes center stage in the middle of an overcrowded table alongside a heap of potatoes, a few heads of broccoli and the like; but the perfect composition is mucked up by a white wig that has been dumped next to the chicken. In “Ecstasy” (2016), the unique play of light and shadow is a tribute to Italian sculptor Giovanni Bernini’s 1652 “Ecstasy of Saint Teresa”. Here, however, the unique composition is modeled after a wooden display of angels at the Metropolitan Museum of Art with the deities irreverently replaced, for example, by the head of Micky Mouse and a garlic press. What is at play here goes far beyond being irreverent for its own sake. Wang seems to be saying, “We’ve invested so much of our lives in these commonplace objects, don’t they deserve the same kind of attention?”

With her previous shows, Wang has already shown a propensity for interweaving the natural with the artificial; here, she deftly collapses the human with the inanimate, the historical and contemporary. While possessing no discerning voice of their own, the objects in her paintings appear to be freighted with deep emotional or symbolic significance.

In Wang’s paintings, the subjects—the human figures—are being treated like objects, whereas the objects present are what demand anthropological scrutiny. Obviously, Wang isn’t the first to endow objects with a voice, a history. What is unique about the exhibition is that it does so in the context of the modern world, when man’s relationship with objects can be described as ambiguous at best. As much as we continue to define ourselves by the things we possess, the era of “fast-anything” has also enabled us to relinquish them alarmingly quickly. How much agency do objects have? Do histories disappear when they are discarded?

The seriousness of these questions is offset by the distinct brand of humor that threads through the works on display. Rather than a hard-hitting critique of today’s rampant materialistic culture, “There is a place with four suns in the sky—red, white, blue and yellow” is really a reflection—and celebration—of life itself. The idea that an object, be it a string of pearls, a pear or a garlic press, can encompass all of life’s complexities.