It is a truth widely acknowledged in Asia that an older Western man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a younger Asian wife. So when Art Basel, the prince of art fairs, acquired ArtHK last year, tongues were wagging about how the fair will change this year. More questions will emerge about identity and positioning with its rebranding as “Art Basel Hong Kong” next year.

This year, the fair boasts a similar ratio of Asian to Western galleries, but some who had participated previously had trouble getting in — this year only 266 of roughly 700 applicants made the cut. This competitiveness was reflected on the floor but not so much in the projects. Though the overall quality of the work in the booths was on par with last year (there was very little of the kitsch Chinese and Indonesian paintings we often see at lesser fairs), there seemed to be a preponderance for images of female genitalia in myriad shapes and forms — some more tasteful than others (the gallery that brought that painting in Hall 3, you know who you are).

Upstairs in Art Futures and Asia One, we found less risky works on display (perhaps the result of the increased booth price this year) and the project section was decidedly tame. Yayoi Kusama’s Flower installation — freakishly large colored flowers (gaudy even by Yayoi Kusama’s standards) — and Choi Jeong Hwa’s inflatable lotuses eclipsed more conceptually challenging work.

One notable piece was “Cong” by Ai Weiwei, the name referring to a classically revered form of jade vessel that traces its origins back to neolithic times. On the exterior are framed numerous letters of reply from a multitude of governmental ministries and departments, all protesting in polite but firm bureaucratic legalese that, no, Ai Weiwei and his studio assistants cannot obtain any further information about the shoddy construction of schools — that which had directly or indirectly led to the deaths of over 5,000 schoolchildren after the Sichuan earthquake of 2008. Inside the cylindrical interior, the particulars of over 5,000 children are hauntingly listed: name, date of birth, age at their untimely deaths, school, and so on. The stark contrast between the exterior and the interior, with the reference to a millennial form of vessel, makes a not-so-oblique suggestion about the nature of power in China.

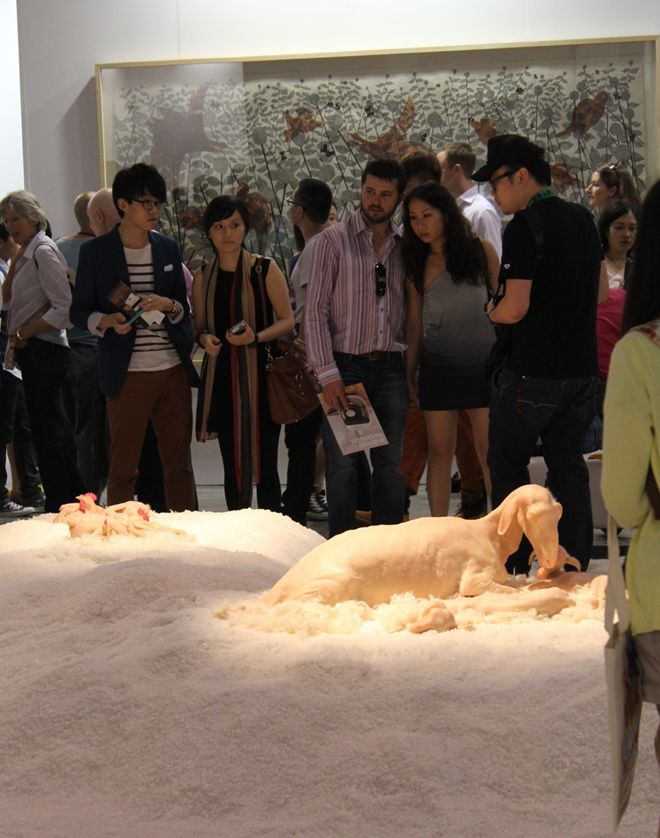

Elsewhere, Shen Shaomin offered an alternative to this populist pathos pop candy floss with a sick/sweet installation featuring small dunes of salt on which a number of hairless and featherless animals, goats, chickens, etc lay snoozing. Pink, alien and delicate, their bodies rose and fell almost imperceptibly, air escaping their nostrils, quietly breathing while visitors gaped and gasped. This near-lunar scene teetered on the cusp between life and death, exploring the perilousness and fragility of natural life.

Another project that stood out — not so much for its brilliance but for its capacity to invoke head scratching — was Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s replica fiberglass dinosaur-and-rhino duo entitled “I didn’t noticed what I am doing” [sic]. The work was supposed to confuse and/or provoke the viewer by presenting two similar looking creatures, one from our current era and a triceratops hailing from the Mesozoic (and somehow as a metaphor about gallery display), but this one-liner was lost on most viewers, who were more concerned about why the installation appeared not once, not twice, but three times across the fair. A case of the galleries having turned up wearing the same dress, it seems — in HK even more of a faux pas. But, as Platform China explained to us, the respective works were all installed in slightly different ways. Platform’s booth had the animals with a puddle of water beneath them, as if the animals had relieved themselves on the exhibition hall floor after imbibing a bit too much during the vernissage.

In terms of sales, reports were up and down. James Cohan did some good business, selling works by many of their artists (such as Francesco Clemente, Richard Long, Bill Viola, Philip Taaffe, and Wang Xieda), as did Chambers, which sold out their exhibition of watercolors by Guo Hongwei (priced between USD $6000–$35000). Pace Gallery reportedly almost sold out its booth. But others such as Lisson, David Zwirner, ShanghART and Magician Space complained of bad sales. White Cube boasted that their Kiefer exhibition in the HK gallery space had “sold very well, including works not on display.”

Outside the exhibition halls, much attention centered on the Pedder building and the galleries (mostly foreign) who’ve been setting up camp there, among them Ben Brown, Pearl Lam Galleries, Gagosian, Simon Lee, and Hanart (with a tiny space at the end of a corridor). This year’s joint openings (including first-time Asia solos for Andreas Gursky at Gagosian, Sherrie Levine at Simon Lee and Anselm Kiefer nearby at White Cube) were marred by a poorly timed renovation of the staircase so that guests, frustrated by the glacial pace of the elevators, ended up braving the scaffolding and dust in their Jimmy Choos just to get from one floor to another. Though the spaces were beautiful, white and gleaming, there was little on the walls that really shone, though Li Xiaojing’s paintings at Pearl Lam were a pleasure to behold.

Elsewhere in Central, at the Shanghai Tang Mansions Huang Rui showed a ping-pong table inlaid with traditional Chinese instruments — a shame that this project was placed in such a cluttered venue where the sounds of the installation were drowned out by the chatter of guests and customary clinking of champagne glasses.

Further afield in Fotan, a very underwhelming artist studio tour was organized, with much of the work ranging from amateurish to decorative — disappointing given the considerable talent in Hong Kong.

Also in far-flung venues, there was a growing buzz about the Art East Island project, with 10 Chancery Lane and Platform China moving in. Though the spaces are relatively small, accessed from fishy-smelling lifts in a somewhat drab Chai Wan industrial building, the ocean views are nice, and Platform China produced a reasonable show by Jia Aili, “Hallelujah.” The most impressive media campaign was for Rashad Newsome’s performance at Feast Project’s new space — which was massively popular (just goes to show that you don’t necessarily need to go to the fair).

These new developments, along with M+ (The Museum of Visual Culture in the West Kowloon Cultural District) have generated the theory that Hong Kong will be become China’s new art hub. Given recent complications on the Mainland with regard to the import and export of artworks, harassing galleries and collectors to pay tax and the arrest of several heads of shipping companies, this theory is quickly gaining momentum.

Somewhere in the grapevine breathes a rumor that Pace is planning to set up a branch in Hong Kong. Meanwhile, m97 gallery from Shanghai is setting up a space, as are Island6 and Studio Rouge, also from Shanghai. Pekin Fine Arts has a space as well, while Galerie Perrotin took up a space in the same building as White Cube. Ausin Tung from Melbourne made the off-beat choice of a space in Kowloon Bay. And then there are the recent Mainland entrants of Pearl Lam and Platform China. And though Hong Kong does not suffer from the problems of censorship and tax issues, there are still major barriers for galleries in Hong Kong.

With the bulk of the market for Chinese contemporary art lying with foreigners, buying in Hong Kong currently makes sense. But if at some point in the future Chinese collectors begin to buy contemporary art en masse and they want to keep their art in China, they will still have to pay taxes when they have cause to import their acquisitions.

There are also the exorbitant costs of running a gallery in Hong Kong due to the high cost of living and — most importantly — rent, which can run up to 20–50 times the rent in Beijing and Shanghai. The realities of these steep overheads will force galleries into showing only the most commercially viable work — a trend already evident. And word has it that even White Cube is suffering from high overheads and slow sales, despite having a strong brand and crack sales team.

In other news, tongues were set wagging over the future of LEAP, one of China’s best print magazines on contemporary art. Founding Editor Phil Tinari was conspicuously absent from Modern Media’s annual prom, which was rained off the Grand Hyatt terrace after an hour in something of a pathetic fallacy (and no doubt much to the chagrin of those bikini girls hired to sit by the pool). Two days later, the ominous tidings broke that Tinari had been “let go,” and that Prada-clad video art maestro Wang Jianwei had been invited to replace him. Wang’s subsequent Weibo response contained no affirmative answer, whilst Beijing’s Today Art Museum merrily reported the news of his accession to the post of Art Director of the magazine. Meanwhile, the Olafur Eliasson sculpture sent to UCCA from Modern Media in honour of Tinari’s accession there has, we can confirm, vanished from the wall. Feelings are facts, indeed. Amid whisperings that the magazine has been hemorrhaging cash, all keenly anticipate an “announcement” said to be forthcoming.

So what can we say? Another year of ARTHK, another round of talks, brunches, VIP scrabbling, oohs and ahs. It’s a sound professional fair, and there is infrastructure going up all over the place (Asia Art Archive, Asia Society, as well as M+ and the Central Police Station, if they do indeed happen) which will surely propel it further. Between these potentially top-notch institutions and the rabid instincts of a relentlessly commercial entrepôt, it would be interesting to see which wins out.