Coming right on the tail of “Singles’ Day” in China (Nov 11), the smell of money permeates the not-quite-APEC blue skies (more here). It is not that bad, really: the autumn is fresh, and we all breathe a collective gasp of relief—though the same cannot be said for our minds. This is especially true in Shanghai this November: almost more than in September and October, all kinds of hubbub and openings follow one after the other, day after day. At a certain point, you realize one thing: whenever galleries put up solo or group shows, the works will almost invariably show up in the art fairs as well. The exhibitions you missed you ended up seeing in your friends’ WeChat “Moments” [WeChat is a really popular mobile social media platform in China], and this more or less rids you of the anxiety of not seeing everything, since in the end you didn’t really miss out on much anyways. There is, however, another trend: previews before openings are getting awfully popular, and these naturally are only open to collectors—which makes you feel very much like a Less Important Person.

In an interview with LEAP in their Art021 special edition Her | Shanghai | Near Future, Anselm Franke, the chief curator of the 2014 Shanghai Biennale, said: “The current aesthetics of hyper-modernity everywhere fetishizes innovation, change, transformation, communication, imagination, dialogue, unlimited possibility. It is an aesthetics of enchantment, hyper-visibility, and, to a certain degree, hybridization. But it conceals the fact that, often, there is no innovation at all, no transformation, and no actual hybridization; in the psychic realm, there is instead ontological fixation and phantasmagoric of identity, as well as a longing for a certain imperial grandeur whose effects we begin to feel again.”

If “ontological fixation” and “phantasmagoric of identity” sound rather oblique, then a “longing for a certain imperial grandeur” is immediately understood by most people—and indeed, it is being practiced as one preaches. The second edition of the Art021 art fair this year still remained at the Rockbund area, part of the Bund in Shanghai. This erstwhile confluence of money and culture of the British elite in the early 20th century has, 80 years later today, taken on a new look. The Art Deco structures are now stuffed with contemporary art. From the single edifice of the National Industrial Bank (NIB) building, the fair has now expanded along Yuanmingyuan Road: from the Laszlo Hudec-designed China Baptist Building, through the Union Church Square, right through the Lyceum Building, the Christian Council Building, and Somekh Building, all the way to the NIB building. A strong whiff of post-colonialism, post-imperialism and capitalism hits you, while the neon decoration along the entrances of the NIB and China Baptist buildings looks a bit like the entrances of nightclubs back in the old Shanghai days when it was the “Paris of the Orient”. Together, the blazing neon and the clashing dark blue theme color, as well as the gingko trees along the street completely lit up in blue against the night sky, put out a seductive appeal outside. This enchanting overexposure swallows up all works exhibited and guests visiting, with form becoming the main content. To use the words of the WestBund Art Fair curator (and artist in his own right) Zhou Tiehai: “An art fair is a piece of art.”

Art021艺博会中实大楼入口(摄影:路易)

Posters everywhere, light boxes, and videos of celebrities uttering good wishes—a festive consumerist spirit pervades this precious piece of land. Collectors leap up on stage: Kelly Ying and Bao Yifeng, the main founders of the Art021 fair, are active collectors and promoters of contemporary art. From the collections of William Zhao, a Hong Kong collector and the special consultant of Beijing’s Council Auctions, along with the collections of Adrian Cheng, the scion at K11 (and much else), Alan Lo, Liu Feichao, Kelly Ying, Chloe Zhao, Jane Zhao, Amy Gao, and Wu Yishen, among others, the exhibition “Showoff—The 4th International Exhibition of Collectors” was put together; it was hard to see a theme in the exhibition. Elsewhere, Wang Wei, the co-founder and director of the Long Museum, along with Sylvain and Dominique Lévy, veteran contemporary Chinese art collectors and the founders of the DSL Collection, Zhao Lingyong, and the young collector David Chau took part in the discussion “Private Pleasure and Public Enjoyment—the Significance of the Turn from Personal Collections to Institutional Collections”, which was the key forum taking place during the fair. If you wanted to grasp the overall transactions of the art fair, you need not inquire from galleries anymore, perhaps—far easier is it just to see which collectors bragged about how much they spent and whose work they bought right there on WeChat Moments.

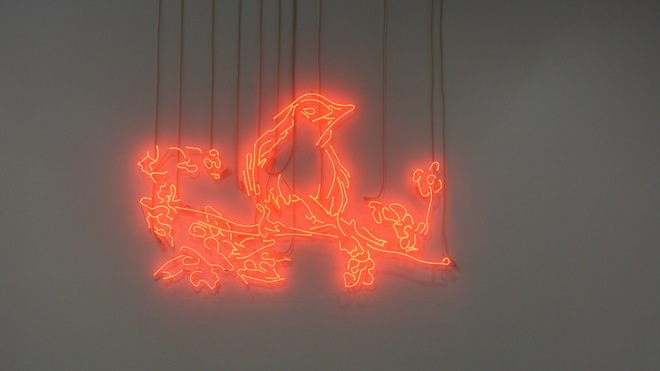

The 54 participating galleries for the most part had larger exhibition spaces than the previous year. On the day before the opening during the collectors’ preview, quite a fair few galleries had already sold over half their booths. The golden teapot—that magical selfie machine—shown at the same time at Antenna Space’s gallery space had already sold three editions on the opening day, according to the gallerist Simon Wang. Huang Yuxing’s paintings, which practically sold out at the solo show, were again a critical and commercial success at the fair. A Thousand Plateaus from Chengdu also had a bustling booth; sales were reportedly excellent. Various major international galleries also brought works by quite a few star artists: Lehmann Maupin and White Cube brought neon works by Tracey Emin, while Antony Gormley’s “figural” sculptures also popped up in the White Cube booth. Beijing’s Gallery Yang, which has something of a focus on new media and digital works, brought works of “computer aesthetics” by Lin Ke, also shown recently. Long March Space exhibited Zhan Wang’s “Flying Stone No.4” as well as recent painting “Stain T19” by Zhu Yu, once known for his subversive performances. Urs Meile’s booth appeared to be a solo show by Xie Nanxing, whose oil painting series Triangle Relations Gradually Changing were even published as an artist’s book during the art fair, with the noted curator Li Zhenhua specially invited to participate, discuss, and curate.

In contrast to the hubbub at the NIB Building, the 7 galleries in the “1+1 Project” in the China Baptist Building were less sanguine about the low footfall due to the unclear directions. “1+1”, as the name implies, had one artist per gallery. Vanguard Gallery brought Bi Rongrong’s collage works; Ren Space, focusing on limited editions, showed paper works from Zhang Peili’s latest solo show. The recently established MadeIn gallery also brought works by He An from the ongoing solo show, while BANK not unexpectedly displayed works by Liao Guohe, not so coincidentally having a solo show in Nanjing’s Sifang Museum—and Liao’s farting doll was for a while the social media darling on WeChat. C-Space, FQ Projects, and Don Gallery respectively brought works by Zhang Shujian, Dai Mouyu, and Zhang Yunyao. The China Baptist Building also grouped together several Hong Kong galleries, like Exit, as well as booths from Budi Tek Museum, Sifang Museum, HOW Museum, and Shanghai Power Station of Art (with advertisement of the Shanghai Biennale plastered over everything). Olafur Eliasson’s light installation, “Your Chance Encounter”, originally meant to be placed in the Union Church Square, was shunted to the 9th floor. Lonely and rather desolate, the work truly could only be encountered by chance.

翠西•艾敏,《我最爱的小鸟》,霓虹灯 (翠西•艾敏版权所有,鸣谢白立方画廊,摄影:路易)

安东尼•葛雷,《1-5幢》,铸铁(安东尼•葛姆雷版权所有,鸣谢白立方画廊,摄影:路易)

The good bits were placed in odd spots: Li Qing’s work “The Last Doctrine—After Repin’s ‘Tolstoy Plowing’” (Hive Art Center) asks the viewer to pass through the people and horses sculpture as well as a painting cut into two; the half-horse sculpture was almost empty on the inside. The form of the work is rather similar to Xu Zhen’s early “dinosaur” imitation of Damian Hirst’s sharks in formaldehyde. ShanghART also displayed Liang Shaoji’s silk installations, just recently shown at their last exhibition. Subodh Gupta’s giant golden heart in the same area attracted hordes of teenage girls taking photos. Back at the NIB building, Boers-Li brought a work by Qiu Anxiong specially commissioned by the fair, “Temptation of the Land: Window Project”, yet the work has not managed to break past his usual visual language and so looked unremarkable. Toby Ziegler’s “Turpentine Quarters” (Simon Lee Gallery) looked rather more interesting than Tony Cragg’s sculpture, which are fast looking old. Hu Jieming’s “The Remnant of Images” has many small-scale documentary videos within the drawers of an archival cabinet; this extends his concern for the remembrance of time, leaving viewers in a state of melancholy and emptiness—the rare work in the fair which makes you stop and really look.

The biggest winner overall cannot but be MadeIn Company, led by Xu Zhen. This artist-cum-boss, who once declared “Art is a business”, launched the “P|Mo” art editions store together with the collector David Chau—and this is undoubtedly yet another conquest of the “MadeIn Empire”. The inner garments printed with P Mo (皮毛) showed the contours of the body; the T-shirts (280 RMB each) and tote bags (100 RMB each) are the artist’s limited editions by MadeIn Company and its director Xu Zhen. Or is “P|Mo” store itself a piece of work? Anyhow, the store will turn into an online store after the fair. Outside, the large sculpture “Eternity” located in Union Church Square links up ancient Greek sculpture with Buddhist figures. Only the heads were missing—whether you see it or not, no thinking is needed.

That an image from Yang Fudong’s “International Hotel No. 2” served as the main poster for the art fair seemed worth pondering. The flaws in the graphic design, however, cannot compare with the mess in the interior design of the fair grounds. Though each booth was not small, the dividers and quality of the installation appeared rough and a bit “tight”. The uncovered pipes, the layout, and the crushing light together with the mismatched gray carpets, the works and people squashed together…the only bright spot were the transactions. Of course, this salesmanship/showmanship will not fundamentally cause any negative influence. Galleries still speak well of the fair, art world insiders were all there, and waves of people came to experience the “good and the great” (gao da shang); the media clamored to report on all this. The chief media sponsor of the fair, Thomas Shao, even lent his name (gua ming) as the honorary chairman of the Art021 Managing Committee, while the overall media partner Phoenix Art had Xiao Ge frantically interviewing on site and producing copy online and on WeChat at a breakneck speed. Clearly, Art021’s links with the local Shanghai art world are solid—and the VIP card allowed discounted access to all major museums and free entry to the Shanghai Biennale. So is this high-end treat the de rigueur goal of contemporary art? When artists throw themselves into this consumerist frenzy, can they still create on their own? Or maybe it’s okay just to devote themselves to this carnival? Let’s just hope this whole scene is not as illusory as APEC blue.

真光大楼一楼,李青的装置,《最后的主义——列宾《托尔斯泰犁田》之后》(摄影:路易)

真光大楼一楼,梁绍基的装置,《命运》(摄影:路易)

胡介鸣,《残影》,多屏录像装置 (香格纳画廊)(摄影:路易)

皮毛店外景(摄影:路易)

新天安堂广场,徐震的雕塑,《永生》(摄影:路易)