Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (1 avenue du Président Wilson, Paris, France)Oct 18, 2013–Feb 16, 2014

Due to various preconceptions, prejudices, or my extended stay in France, I have never felt the urge to see or understand Zeng Fanzhi’s works. Fortunately I recently had the opportunity to become closely acquainted with them at his retrospective exhibition, currently showing at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. The comprehensive exhibition catalogs the trajectory of the artist’s 25-year career. In addition, I was the translator for Zeng Fanzhi in his interactions with the French media and was thus able to converse intimately with him and gain a deeper understanding of the artist. I saw his Paris exhibition several times. I accompanied him as he strolled through the museum with French journalists in tow, looking at each piece and listening to his answers to the journalists’ questions. I attended the star-studded opening where everyone vied to be photographed with the artist, or alongside the works that have fetched astronomical prices at auctions. After the dust had settled a week later, in the midst of writing this article, I returned to the art museum as an ordinary visitor and saw the entire exhibition again from beginning to end one final time.

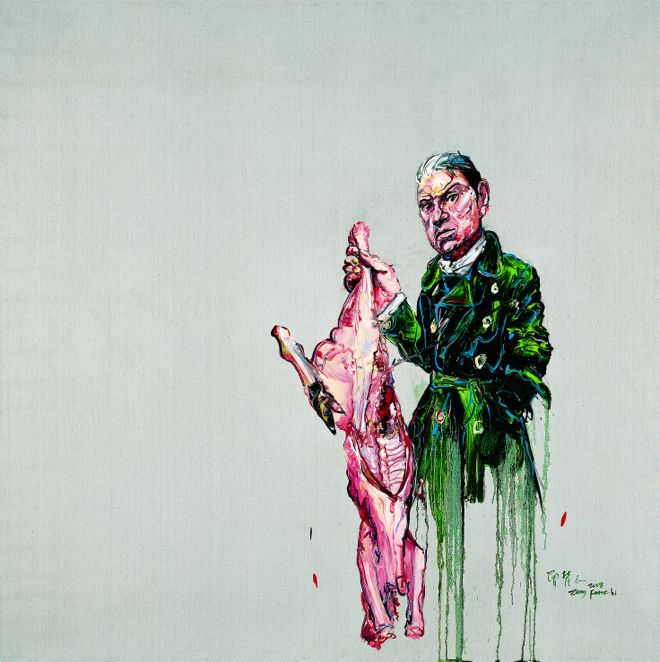

The exhibition was three years in the making. The museum director Fabrice Hergott emphasized that “it seemed important to choose an artist, to show him like a Western artist, to give him space and all the protocol and apparatus deployed for a European or Western artist.” The exhibition brings together 37 oil paintings and two sculptures from 1990 to 2013 sourced from museum and private collections, and the artist himself. Zeng enjoys a high level of name recognition in China and abroad, but French audiences are generally unfamiliar with the four important phases of the artist’s creative journey over the last twenty-plus years. The exhibition covers his recent large-scale polyptychs, his portrait series, his highly coveted mask series, and his intensely expressionistic hospital series. Important works on show include “A Man in Melancholy” (1990), completed during the artist’s third year of university; “Hospital Triptych No. 2” (1992), the work which first caught the eye of the famous art critic Li Xianting; “Meat, Reclining Figures” (1992), currently in the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum’s collection; and “Mask Series No. 6” along with “The Last Supper” which created media buzz by fetching incredible prices at auctions at Christies and Sotheby’s in 2008 and October of this year, respectively.

曾梵志,“协和医院三联画2号”,180 x 460 cm (三联画), 1992

曾梵志,“面具系列6号“,200 x 360 cm, 1996

Due to considerable ingenuity in the exhibition’s design, the works seem to echo and influence each other although they are placed in different exhibition halls. Audience members looking at one piece can always catch glimpses of works preceding or following the work they are viewing. For example, when standing in the first exhibition hall featuring large-scale abstract landscapes, visitors can glimpse representative works from the transition period just prior to the works in front of them such as “Untitled” (2002), “Night” (2005), “Swimming” (2006) and so on. These images, resembling still frames from a movie, were already beginning to show traces of disturbance and chaos, but they had not yet progressed to the point of winding across the entire canvas, as in recent works. His images are often structured into two diametrically opposed counterpoints—a thematic image vs. chaotic brushstrokes, sparseness vs. density, light vs. dark. If you note the dates his works were completed, you will discover the artist experimenting with several different elements in the same period of time. For example, between 2002 and 2004, the artist was not only continuing with the mask series, he was also removing the masks and completing large-scale portraits on white backgrounds which were relatively simple in style, and experimenting with wilder brushstrokes. When viewers arrive at the fountainhead of the artist’s creative work—early paintings revealing the heavy influence of Western tradition—they must then walk back the way they came to exit the exhibition hall. In this way, they revisit the entire exhibition in chronological order, from his early works to his more recent works; viewers gain a deeper understanding of the continuity and transformation of the artist’s style from a Western point of departure to a highly individual style with visual symbols and a unique artistic language. This design also coaxes the viewer into considering the ways the artist continues to strive for and develop his personal language of painting.

A museum docent excitedly pointed out to me one of Zeng Fanzhi’s 2009 self-portraits where the artist is depicted in red, barefoot, sitting on a short bench with a paintbrush in his hand trailing a streak of white across what could either be the background or a painting within the painting. He told me how much he loved the piece, how deeply he felt the artist’s loneliness, calm, and assurance through the painting. He turned and pointed to “Mask Series No. 5” (1998) which was directly facing and said, “Look at this painting, from his clothing, we can surmise that he might be a high level technician. The plane flying behind him might signal that he works in the aerospace industry. You can see tears leaking out from beneath his mask, which clearly alludes to the sense of confusion and loss many Chinese feel in modern society.” For a Western audience, Zeng Fanzhi’s figurative paintings do not present many cultural barriers; they are easy to approach, and almost anyone can understand and interpret them in a personal way.

Starting in 2000, Zeng Fanzhi’s works initially won the favor and support of Western collectors. Due to their considerable economic resources, many Chinese buyers soon joined in, causing the price of his paintings to soar, breaking auction records. The reason Zeng Fanzhi has become an art market darling is mainly due to his melding of traditional painting techniques (familiar to Western audiences) with his personal experiences in Chinese society. After four solid years of rigorous training at the Hubei Academy of Fine Arts, Zeng Fanzhi’s paintings not only display exquisite skill, but they also deal in subjects familiar to the West—portraits, still life, and landscape. Additionally, he has chosen figurative realism—a style which has been largely neglected or even disdained by European and American artistic circles since the post-1950s advent of abstraction, minimalism, installation, and video installations. The shadows of many Western masters flicker through them too—Chaim Soutine (1893-1943), German Expressionist Max Beckmann (1884-1950), Francis Bacon (1909-1992), Giorgio di Chirico (1888-1978), Willem de Kooning (1904-1997), Jackson Pollock (1912-1956). He also draws on Renaissance paintings, like “The Last Supper” (1494-1498) by Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) and “Young Hare” (1502) by Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528). Accordingly, Zeng’s paintings are very accessible to Western collectors, or rather, Zeng’s paintings are able to pass more easily into the world that Western collectors and audiences inhabit than perhaps traditional Chinese ink paintings or calligraphy, which are clearly marked as “other.”

Zeng’s style is apparent in the exaggerated proportions, uniform masks, and wildness of his recent brushstrokes, along with his personal experiences. The “Hospital Series” derived from Zeng’s impoverished environment while growing up, which forced him to use the restroom at a nearby hospital every day. The inspiration behind “Meat, Reclining Figures” and “Man and Meat” came during one of Wuhan’s blisteringly hot summers, when the artist saw an employee from a butcher shop cooling off by lying on top of a hunk of frozen meat. These images seem incredible today, adding a sense of legend to Zeng’s works. The most hotly sought-after “Mask” series was inspired by the artist’s experiences in moving to Beijing and witnessing how city life changes human beings, distancing people from each other. Here, he taps into a common sense of isolation which surpasses the boundaries of nations, culture, language, and ethnicity. The artist creates a window into the current state of Chinese society, and in some ways even affirms many Western preconceptions about China. All of these elements combined have made Zeng Fanzhi’s works extremely popular on the international market.

However, the halo cast upon him by the market places Zeng at risk of being pigeonholed as a commercial artist, so that his works are not as well understood, exhibited, and researched by critics, museums, and academics. The current solo exhibition at Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris is undoubtedly an excellent entry point for Zeng into the important museums of the West. Of course, museum exhibitions are not enough to establish an artist’s name in art history. In the end, this relies on the work of serious critics and academic scholars. Although Zeng Fanzhi enjoys much support from international galleries and collectors, there is still a lack of in-depth analysis and scholarly study of his works. Even the literature introducing his work at the current exhibition seems empty and lacking in new insight. For example: “Zeng Fanzhi has been deploying since the 1990s a distinctive language marked by his kinship with both Asian art and the many Western influences he has been subjected to. Confronted with this all-embracing style, the viewer is reminded of Chinese landscape painting at the same time as he thinks of Warhol, Bacon, Balthus and Pollock.” It remains to be seen whether Zeng Fanzhi can transcend the market and garner institutional recognition from museums and academics, and whether he can have a profound impact on international art circles. This depends on whether critics and academics can themselves transcend the framework of a certain period in the history of Chinese society, and whether they can look beyond a superficial interpretation of “East meets West” when faced with his works.

曾梵志,“自画像 09-08-1”,200 x 200 cm, 2009

曾梵志,”培根和肉”,200 x 200 cm, 2008