“Filter the Public”: projects and exhibitions

Shanghai World Financial Center (No.100, Century Ave., Pudong New Area, Shanghai) Oct 25–Nov 10, 2013

In celebration of its fifth birthday, the Shanghai World Financial Center (SWFC) plays host to “Filter the Public,” a series of projects and exhibitions initiated by the curators Lise Li and Kenta Torimoto, which involves a number of Shanghai’s prominent galleries including Aike-Dellarco, Art+ Shanghai, Art Labor, Around Space, Beaugeste, Don Gallery, James Cohan Gallery, M97, OV Gallery, Pearl Lam Galleries, Shanghai Gallery of Art, ShanghArt, and Vanguard Gallery. The exhibition, which takes place between the first and third floors of the SWFC shopping mall, also features a number of special projects by independent curators and artists organized by Leo Xu, Mathieu Borysevicz, and Weng Zhijuan.

Representing ShanghArt, MadeIn Company’s “Divinity-Marx” is perhaps one of the most recognizable—and surprisingly relevant—pieces on display here. So much of MadeIn’s work is based around a relentless cycle of vagueness, contradiction and subjectivity, something SWFC’s setting actually enhances (which cannot be said for every work on display here). “Divinity-Marx” is at once transcendental and ordinary, a totemic form undermined by its mass-produced polyurethane foam base. It’s monumental both in its size and monochromatic, jet-black coloring—there’s more than a little bit of a minimalist aura to this piece, which is all the harder to reconcile with its pseudo-religious, totemic “other half,” which seems to have loftier ambitions than physical presence alone. Any attempt at rooting it in the material world is contradicted by these grand allusions; similarly, any attempts to understand it as a purely spiritual piece are immediately derailed by its tactility and undeniable “presentness.” All of this would likely play out in any context; it just so happens that its incidental placing in SWFC’s lobby only accentuates the contradiction between the material space and transcendental notions that are inherent in the piece, and it is often from this game of interpretation and reinterpretation that MadeIn’s pieces derive their power (not to mention their entertainment value).

While most curators chose not to focus on SWFC’s commercial setting, the “Free Art Zone” (“initiated” by Weng Zhijuan and featuring work from Li Xiaofei, Lu Jiawei, Pulsasir, Qu Yi, Wu Ding, Xia Tao, and Yue Luping) seems at least partially site-specific. The wall text accompanying the (unfortunately quite negligible) space dedicated to the project asserts a dedication to an expansion of artwork from the gallery space into contemporary, public environments—the case in point is, obviously, shopping malls. As the project’s title alludes, the works here are particularly interested in the notion of Shanghai as a Free Trade Zone, and as such engage in this dialogue using explicitly commercial signs—indeed some pieces are set up to be almost interchangeable with genuine advertisements. “Art” photographs share the same eye-catching mediums (in this case a lightbox) as the advertisements nearby. If art is destined to become increasingly displayed outside of the white cube format (as has long been suggested but not too often realized), it is interesting to see artists practically engage with new forms of exhibition space—however, here unfortunately I can’t help but feel that the “Free Art Zone” falls a little flat, not due to its substance (the idea is one with a lot of potential), but due to its slightly marginalized position here. Given a more dedicated or expansive space however, Weng Zhijuan and co. could be on to something.

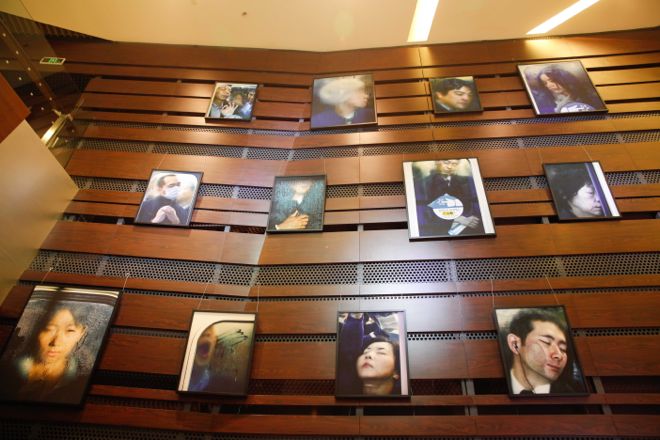

Michael Wolf’s wonderful “Tokyo Compression” series is for me reason enough to visit SWFC—his portraits of Japanese subway commuters have been widely reproduced online, but are entirely worth seeing in the flesh. Every subject is a victim of the amoral gaze of the lens, as well a hero of endurance. They not only force you to relive their discomfort, but also, somehow, in the very act of witnessing it, even through the displaced medium of the photograph, render you implicit. Some are partially hidden behind the steamy windows of the subway carriage; some seem to be trying desperately to shut themselves off, while others still return the camera’s insistent stare. The result is striking, prompting us to question the rationality (and potential physical risks) behind the pseudo-rituals of modern life. It’s unclear whether it was a conscious decision on behalf of M97’s curators to elevate Wolf’s photographs above normal eye-level or if this design choice was a result of the limitations of the space, but does seem a shame to have such simultaneously alienating and intimate portraits positioned at this slightly inaccessible height.

Two entirely different (but equally interesting) series that stood out for me come courtesy of James Cohan Gallery. Li Wenguang’s quasi-grid painting/sketch hybrids immediately bring to mind architectural drawings, all while hinting at a certain still life tradition (best exemplified in “Potted Plant 5,” and suggested by his choice of lo-fi, “simple” xuan paper for a canvas). The duality of mathematical rationale and creative “landscaping” (Li utilizes ink, pen and acrylic paint to create alternately flat, multi-dimensional and disruptive surfaces) culminates in an often dynamic and always interesting picture plane, not to mention adding to the always tense dialogue between abstract form and geometric logic.

Also representing James Cohan is Mark Strand’s decidedly intimate series of handmade, painted paper collages. The pieces are both expressive and controlled; Strand avoids excess, both in his use of paint and in his choice of dimensions. Each collage feels very precious, an impression only added to by our knowledge that Strand crafted every aspect of the piece himself. Despite being works of complete abstraction, it’s almost impossible not to project our own associations (particularly of landscapes) on to the pieces. And while it is clear that Strand has an eye for color balance, these works never feel coldly technical—we can see the strokes where Strand applied the paint by hand, the tears on the paper are rough, and each piece is layered just heavily enough to make the works feel very tactile. An understated and evocative series.

While it was inevitable that “Filter the Public” would run into some difficulties with its venue, there are a number of very special works on display here, some of which utilize the space very well. It’s important to experiment with modes of exhibition – while some works may be best suited to the white cube, others require expansion into the external world. To ignore fact is to be close-minded to the point of irrelevance, and while SWFC may not be an ideal setting, “Filter the Public” is an interesting contribution to a much wider dialogue.