Samson Young: “Orchestrations”

Para/Site (22/F Wing Wah Industrial Building, 677 King’s Road, Quarry Bay, Hong Kong, China), May 27–Jun 12, 2016

You might not have guessed from Samson Young’s eclectic work that he is a classically trained music composer; or maybe you would, given how intellectually challenging some of his pieces are. But that is the exhilarating aspect of navigating through his works. Just when you feel your mind is being bogged down by all that Hong Kong history, that familiar Cantonese nursery rhyme comes tunneling through. And when you think that sound might as well come from any bell in any cathedral or school in the world, it transpires as that of a Nazi-confiscated bell that survived WWII. If there is anything consistent about Young, however, it is his unrelenting desire to create a language—a set of decrees, if you will, that is uniquely his own.

“Orchestrations”, born of a year of musicological research into the history of orchestras, continues the artist’s obsession with creating a formalistic narrative that can, at times, seem a tad chaotic.

The modern orchestra in the Western tradition is a relatively recent conception. Previously, music-making had been less reflexive, about picking up an instrument—be it a violin, flute, or cornet—and playing it. It wasn’t until the early 1600s, when an Italian composer by the name of Claudio Monteverdi came along, that the tradition of writing music for a specific ensemble into being.

Fast forward 400 years and Young’s exhibition is dissecting the power play inherent in idea of the orchestra. He subsequently uses this to question the power of language, the flow of information, and identity politics.

A newly commissioned video work, “Orchestrations”, weaves together footage of Hong Kong community orchestras and a series of interviews, provoking the reimagination of relationships between composer and musicians, performers and the audience.

In a sense, the idea of “community orchestras” hews to Cornelius Cardew’s Scratch Orchestra. The English experimental composer’s piece “Paragraph 7” (1971) asks that each orchestra member sing a word from Confucius for a set number of times, sustaining each repetition for the duration of their individual breath. When it is time to move onto the next line, each member takes their next pitch from another vocalist in the group. As such, the pitch content of the piece gradually narrows until there is one note left. By allowing anyone—as long as they can hold a pitch—to participate, this constitutes a “freeing” of the art form; yet Cardew’s method was also highly formalistic—in fact, not unlike Bach’s structure-led approach.

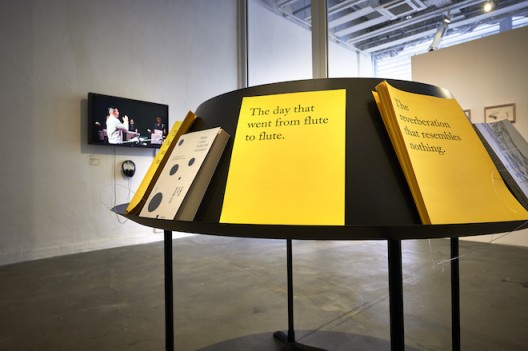

For “Orchestrations”, the instructions are laid out in an oversized tome, its first page noting the myriad of meanings that an “orchestra” can take on—as a space, sculpture, unity or army, among others. This is not Young’s first orchestra. The brilliant “Anatomy of a String Quartet” (2014) examines the way technology can be reconfigured to act as a musician’s body. Inevitably, a flesh-and-blood orchestra is more difficult to control than one made of laptops and iPhones. The moral implications for a human orchestra are also much greater.

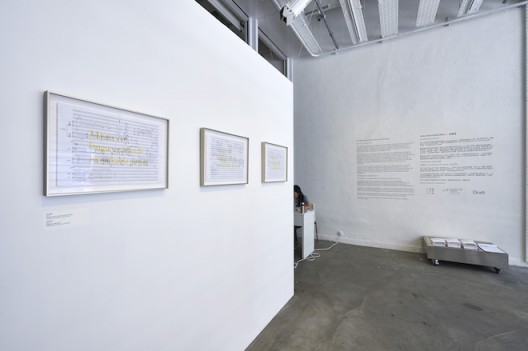

From afar, “Mastery of Language Affords Great Power” (2016) appears from afar like any other musical score. On closer inspection, however, it becomes clear that such cheeky similes as “crisp as an Asian pear” and “shine like justice” have taken the place of traditional musical terms. While “Asian pear” alludes to Young’s cultural identity, “justice” is a nod to the artist’s long-standing interest in identity politics. And it is at this point that the personal effortlessly spills over into the socio-political. Far from being a random dictum, “Mastery of Language Affords Great Power” references Frantz Fanon, the Martinique-born philosopher and revolutionary famous (among other things) for the idea that “to speak means to be in a position to use a certain syntax…to assume a culture” when analyzing the inferiority-superiority complex between the colonized and his conqueror in his 1952 book Black Skin, White Masks. Hong Kong obviously suffered from a similar complex during the British colonial years—the effects of which arguably endure today.

Opposite Fanon’s quote, viewers are confronted with “SDIHK” (2015), a series of three black granite slabs upon which is inscribed “to speak a language is to take on the world.” Beyond the formidable statement, there lies a slew of staffs, variously expanding and constricting at will and taking on spontaneous and bizarre shapes and forms. But alas, are they really spontaneous? Adjacent to “SDIHK” and hung neatly on a white will, “Pastoral Music (But It Is Entirely Hollow)” (2015) brings Young’s obsession with warfare to the fore by weaving together a beguiling assortment of graphical notations. A “BOOM” there, a “KA” here and a series of “Wa” later, we are left with the perverse thought that war and its weapons can somehow can beautiful.

Something, though, remains to be resolved. This eclectic mix of forms, shapes, and notations look mighty extravagant; yet it is hard, even for someone who knows how to read music, to make sense of it all. And herein lies the paradoxical nature of Young’s notational madness. What if it is not made to translate into actual music? Will its beauty only ever make sense on paper? Young’s “The reverberation that resembles nothing” (2016), inked on a sheaf of yellow leaflets, is the musical equivalent of W.H. Auden’s “poetry makes nothing happen.”

It would be presumptuous to think that Young is an anarchist. In fact, that could not be further from the truth. In deconstructing the old, Young is also building the new. While the show might repudiate traditional ideas of the orchestra, this does not make it a rejection of formalist ideas. Instead, the artist’s curious compilation of compositions, suggestions, aphorisms, and graphics borders on the obsessive. In ditching one set of ideals, the artist constructs a language that is uniquely his.

Young once said during an interview, “Only utopians would take pleasure in building things and institutions and organizing people socially…in making ensembles.” Standing amid the chattering crowd on opening night, one could not help but be sucked into the heady swirl of treble clefs, onomatopoeia and graphical notations that is, perhaps, Young’s version of utopia.