Pearl Lam Galleries (9 Lock Road #03-22, Singapore), July 14 – September 4, 2016

Every year, for a single day, the island of Bali grinds to a halt. No planes thunder overhead, and its bustling beaches lie empty. The streets are deserted, and Bali’s residents are all indoors, meditating or even fasting. The following day, the new year is celebrated and Bali thrums with energy once more. This single, silent day, Nyepi, has inspired “In Silence,” the latest group show at Pearl Lam Singapore. Group shows involving artists with disparate practices often rely on themes surpassing the generic; but there may be a saving grace here in that evocative image of an entire island going stock-still and silent for day.

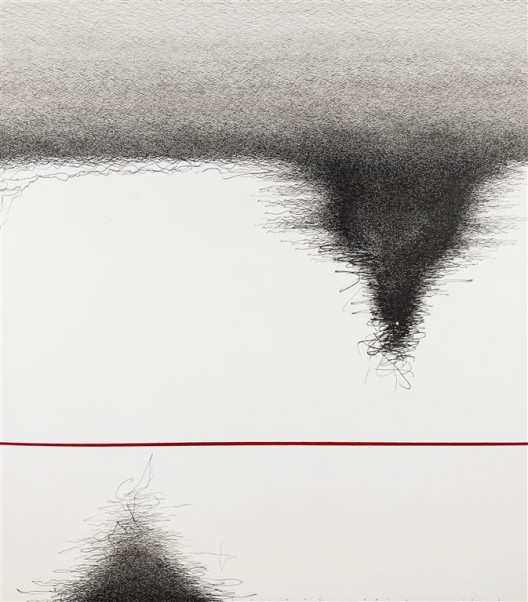

Golnaz Fathi’s untitled canvases are derived from the Iranian calligraphic tradition of Shiah Mashgh, or black practice, the origins of which may be traced to ancient calligraphers practicing letter-forms without regard to content, making use of as much of each page as possible. Fathi’s meditative take on this makes for a good fit to the exhibition’s theme, with her repetitive marks forming a kind of visual susurrus. Getting lost in her delicate, dense traceries of ink is a joy. However, some combination of lighting, texture, and color leaves the inked portions seeming hemmed in, suggesting flatness and constriction.

The solemnity (bordering on somnolence) of a lot of performance art also seems appropriate to the show’s theme, with video documentation bridging the medium’s ephemerality with the commercial concerns of the gallery.

Tao Hui’s “Talk About Body” (2013) is mostly notable for his deployment of impersonally scientific language to describe his physiognomy, which apparently differs from the average Han Chinese male. At one point in the video, Tao says: “My brain is round-shaped, which is exactly opposite to the square shaped brains among ordinary males of Han Nationality. I’m more close to females in characteristics, with slim torso and limbs, low content of fat, and particularly small-boned, which makes me agile and drought-enduring.” The added stiffness of the scripted, on-screen audience, however, nudges this video in the direction of farce.

The split between performing for a live audience and performing specifically for video has long been contentious, and though the performances in “In Silence” appear to lean towards the latter kind, the opening night also featured a durational performance of “Eins und Eins” (2016) by Melati Suryodarmo. A video presents a record of these actions, though this is rather outdone by the spattered ink which also records the performance but in a different register. Known in the performance art world for her grueling durational performances, Suryodarmo’s notoriety ballooned when a video clip of her “Exergie — Butter Dance” became popular online (to the tune of c1.7 million views before being taken down due to copyright) after having its audio replaced with Adele’s “Someone Like You” — arguably, this offers further testament to the potential effects of documentation on performance.

As for the Singaporeans in the show, “In Silence” features Ezzam Rahman, the recent joint winner of Singapore’s President’s Young Talents award (and the People’s Choice Award). His floral skin-sculptures are by and large overshadowed the installation as a whole, which begins with the chance find of a snapshot, and wends its way through the luridly-lit images of what could be spas or massage parlors. Via the works’ profane, conversational titles, there’s a sense of being addressed directly by the artist and the potential to evoke atmospheres of tension, humor, and eroticism—but probably not any flavor of meditative introspection.

A counterpoint to these performative, even visceral works can be found in Singaporean Zen Teh’s geometric works which exude an industrial, minimal coolness — though in the case of “Dual/Duel” (2016, which includes shards of mirror mounted on the wall as if stabbed through it), this is marred by what would otherwise be incidental flaws in its fabrication. Were it not for almost imperceptible things (an inexact bend here, or a slight peeling of the print there), what might appear like wounds piercing the world are rendered less impactful. Her other work, in collaboration with Sharifah Nasser, thankfully achieves greater harmony: brute, rectilinear concrete paired with monochrome photographs.

Though strong enough in their own right, like many of the other works here, these fall only tenuously under the show’s broad theme. In a roundabout way, however, such isolation does suggest the seclusion imposed by Nyepi, leaving some hope for the exuberance that follows.