by Luise Guest

Lindy Lee: Moon in a Dewdrop

Museum of Contemporary Art (Sydney, Australia) Oct. 2 2020– Feb. 28, 2021

Replicas, postmodernism and ‘bad copies’

I vividly remember seeing Lindy Lee’s early works when they were first exhibited in Sydney in 1985 in ‘Australian Perspecta’ and 1986 in the ‘6th Biennale of Sydney’. Grainy, velvety black photocopies of famous faces – portraits by Jan Van Eyck, Rembrandt, Ingres, Artemisia Gentileschi and others from the western art historical canon – were arranged in rows or grids. They gazed out from behind layers of acrylic paint, or wax that had been partially scraped back. Hints of darkened visages emerged through cobalt blue or deepest crimson pigment, unfamiliar and mysterious, their characters both concealed and revealed by the artist’s manipulations.

These shadowy works powerfully conveyed a sense common to artists and writers of my generation (and Lee’s): we were far from the action, on the other side of the world. The cultural centres, the ‘real’ art hubs, or so we thought then, were London, Paris, Florence, New York. We Australians were exiled to the periphery, inhabiting a postcolonial shadow world, a simulacrum – a pale photocopy, faded by the tyranny of distance. The art history we studied was almost entirely European and American; we feasted on images in reproduction, leafing through books with color plates of Renaissance masters, and queued for the (very occasional) blockbuster exhibition of works loaned from overseas collections at the state galleries. In that 1980s heyday of postmodern theory Lee’s works were discussed by critics and academics invoking Walter Benjamin and Baudrillard, but for me their interest lay in the connection forged between the artist and the mechanical reproduction. They suggested the angst of someone searching for a relationship across differences of time and culture.

Untitled (After Jan van Eyck), 1985, Courtesy the artist and Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney and Singapore

Lindy Lee, The Silence of Painters, 1989, Museum of Contemporary Art, gift of Loti Smorgon AO and Victor Smorgon AC, 1995

Lindy Lee, Book of Kuan-yin, 2002, Courtesy the artist and Sutton Gallery, Melbourne

But there was more to Lee’s search than the general Australian awareness of the colonial ‘fatal shore’. Lindy Lee was born in Brisbane in 1954 to parents who had immigrated from China. She grew up in the (then) stultifyingly parochial suburbs of Brisbane during the era of the racist White Australia Policy; just a few years earlier, in 1947, Labor politician Arthur Calwell had notoriously ‘joked’ in parliament that ‘Two Wongs don’t make a white’. This immigrant upbringing, and her experience of being the only Chinese child in her school, left Lee uncertain of her identity. Like other children of Australia’s post-war migrants, she felt she was somehow inauthentic – not quite Australian, nor quite Chinese. Her early, experimental work with photocopies examined her own sense of being a ‘bad copy’, an altered, faded reproduction of the ‘real thing’.(1)

Lee loved the aesthetic and conceptual possibilities of primitive 1980s photocopiers, with their frequent accidental spillages and smears of carbon, and the increasingly pale images they produced when the toner was running out. The seductive blackness and loss of detail intrigued her. Even in those early experiments she was, quite unintentionally, exploring the same materiality as Chinese ink painters. The chemistry of carbon and the aesthetic impact of blackness appealed to the Literati whose carbon-based ink created subtle gradations of tone, from deepest black to the palest hint of wash, just as the sooty black replicas of Old Master paintings held infinite expressive possibilities for Lee.

In the next phase of her work Lee turned from appropriating European paintings to digitising and manipulating family photographs and images borrowed from Chinese rather than Western art history. These became her earliest representations of her Chinese heritage. She began with a photograph of her mother, a strong matriarch who had escaped the post-1949 persecution aimed at those from the hated ‘landlord class’ to join her husband in Australia. It was a long and arduous journey via Hong Kong, with two small children and a suitcase with a false bottom hiding the family’s gold. The courage of a woman who was forced to spend years apart from her husband, who had arrived in Queensland years earlier, is repeated in the daughter’s journey to rediscover her Chinese ancestral roots, developing a transdisciplinary and transcultural practice that celebrates her hybrid identity.

Buddhism and the Ten Thousand Things

It was only after many trips to China exploring her family heritage, and a deep immersion in the practices of Zen (Chan) Buddhism and Daoism, that Lee felt secure enough in her Chinese/Australian identity to produce her mature body of work grounded in East Asian philosophy and aesthetics.(2) A comprehensive survey exhibition of her work at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, ‘Moon in a Dewdrop’ (the title is a reference to the writing of 13th century Japanese Zen master, Dōgen) sourced from private and public collections, and the artist’s own archives, covers the full gamut of her practice. The more than 70 works brought together in the MCA demonstrate Lee’s versatility, from her earliest explorations of the photographic replica to recent experiments in ‘flung bronze’ developed from the Zen painting tradition of ‘flung ink’.

Lindy Lee, Listening to the Moon, 2018, stainless steel, image courtesy the artist and Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney and Singapore, © the artist, photograph: Ng Wu Gang

At the entrance to the concrete monolith that is the new wing of the MCA, the first work we encounter is ‘Secret World of a Starlight Ember’ (2020), a curved ovoid form of stainless steel pierced with thousands of tiny holes. Reflecting the harbour with its passing ferries, the blue of the sky, and the faces of passers-by, its minimalist beauty is intended to reference the Buddhist belief that human beings and the universe are one. Lit from within at night it recalls a map of constellations. The void at its centre, while an irresistible lure for the Instagram selfie and the narcissistic gaze into its reflective surface, reminds us that Buddhism and Daoism are replete with paradox; simultaneously symbolising materiality and immateriality, it represents tian xia – everything under heaven – as interconnected.

Lee told Elizabeth Ann MacGregor, the director of the Museum of Contemporary Art and the curator of ‘Moon in a Dewdrop’, that a work created in 1995 (and recreated for the exhibition) marks her self-discovery. ‘No Up, No Down, I am the Ten Thousand Things’ was made when Lee had returned from China and was ‘released from the imprisonment of being either Chinese or Anglo or this or that’.(3) The installation of approximately 1200 small works made with ink ‘flung’ over photocopies covers the walls, floor and ceiling with blue, red and black rectangles. The Chinese and Japanese technique of ‘flung ink’ was practised by Zen monk painters following meditation. The apparent paradox of finding purpose and meaning in what at first appears spontaneous and random is a metaphor for seeing patterns in the universe and recognising the connection between the self and the natural world.

Without question there is a trace here of Lee’s early interest in the pure abstraction of Ad Reinhardt and Mark Rothko, seen also in the modernist grid presentation and strong reds and blues of her earlier photocopy works. More importantly, though, this was the first work Lee made with the explicit intention of exploring her relationship to Buddhist philosophy and practice.

Paradox and duality recur in Lindy Lee’s work, and in her life. The art writer Julie Ewington describes Lee as an artist who has had, essentially, two careers, ‘remaking’ herself during the year of her Asialink residency in Beijing in 1995. Intending to study calligraphy, Lee realised that being unable to read Chinese characters she was drawn instead to the sooty materiality of ink itself. Ewington cites a conversation between the artist and Suhanya Raffel: ‘The notion of ‘darkness’ in her work began to take on another meaning altogether: here the dark might begin to signify, in consonance with Buddhist philosophy, “the void that holds everything and nothing”’.(4) The ‘ten thousand things’ (a phrase found many times in the Dao De Jing, attributed to Daoist philosopher Laozi) refers to everything in the universe, to the fluxing, see-sawing, reciprocal relationship between yin and yang that contains this void holding within it ‘everything and nothing’. Polarities of masculine/feminine; light/dark; past/present; eastern/western; Australian/Chinese – the ‘this or that’ that Lee described in recounting her uncertain hybrid identity – are thus no longer binary opposites but, rather, relational aspects of qi (the breath, or the life force).

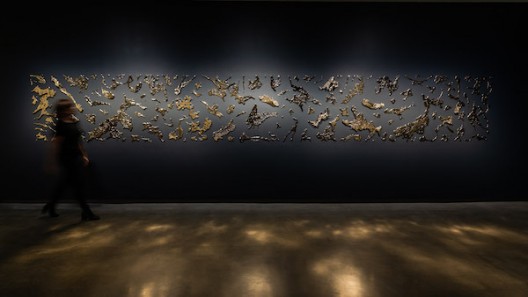

These ideas are further developed in Lee’s experiments with flinging molten bronze, a breathtakingly physical, difficult, and dangerous process. The ladle containing the liquid metal (at 1200 degrees centigrade) weighs 10 kg and the artist is suited up in heavy protective clothing as she ‘flings’ (slowly, deliberately, and following meditative breaths) the bronze onto the concrete floor of the UAP foundry in Brisbane. A documentary video of the artist at work reminded me of observing groups practising tai chi in Chinese parks. Inevitably, too, there is a faint echo of the film of Jackson Pollock at work shot by Hans Namuth in 1951 – Lee’s actions are similarly performative, but much less self-conscious. Her measured gestures result in ethereally beautiful works such as ‘Seeds of a New Moon’ (2019), a collection of solidified, burnished bronze shapes carefully arranged on the wall. They suggest a view through a microscope of biomorphic forms, tiny component parts of an enormous universe, moving in unknowable rhythms, quite oblivious to human attempts to control nature.

Lindy Lee, No Up, No Down, I Am the Ten Thousand Things , 1995/2020, Courtesy the artist and Sutton Gallery, Melbourne

Fire, Water, Air, Earth and Metal

Lee’s immersion in her ancestral Chinese culture has influenced numerous public sculpture commissions in Australia and in China. In ‘Moon in a Dewdrop’ this aspect of her practice is represented by ‘scholar rock’ forms from the ‘Flame from the Dragon’s Pearl’ series, in mirror-polished bronze. ‘Unnameable’ (2017), recently acquired along with a suite of 12 large works on paper for the collection of the Queensland Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA), references the traditional appreciation in China for gongshi, or scholar’s rocks. Limestone shaped by elemental geological forces (sometimes assisted by perforating rocks with holes and immersing them in the waters of Lake Tai for hundreds of years) developed into elaborate, fantastical shapes. Large rocks were an integral part of garden design, a metaphor for the mountain homes of the Immortals. Small rocks were highly prized ornaments in the studies of scholar bureaucrats, symbolising the transformational forces of nature.(5) Lee’s scholar rocks are shaped by fire and water when molten bronze is poured and cooled to produce fluid, organic-seeming shapes.

One of the most peaceful rooms in the beautifully designed exhibition spaces contains a series of suspended paper scrolls which have also been altered by exposure to fire and water. The 2011 ‘Conflagrations from the End of Time’ series references the teachings of Buddhist masters who likened the universe to an infinite net. Intricate patterns are created by holes burned in the paper with a soldering iron, casting lacy shadows on the wall behind them. They curl up very slightly at the bottom edge, appearing weightless, shifting very slightly in the slightest movement of the air. They suggest the passage of constellations across night skies. Burnt and stained surfaces reveal the processes of their creation – Lee sometimes left these scrolls of paper outside in the rain and the sun allowing time and natural phenomena to make their marks. They are echoed by more recent works in which mild steel is cut into lacy patterns. These too reflect the teachings of Daoism: they are both material and immaterial, form and void, shadow and substance.

The Moon in Water

Lindy Lee’s deceptively minimalist works are underpinned by great discipline and knowledge, like the master calligrapher dashing off apparently effortless characters that belie the lifetime of practice. Lee has practised a form of meditation called zazen – sitting meditation – for many years. It was the foundation of Dōgen’s Zen practice; he called it ‘without thinking’, a pathway to freeing oneself from anxiety and confusion.(6) Through her deep immersion in the theory and practice of Zen, following the teachings of this 13th century Japanese monk who brought Zen Buddhism from China to Japan, Lee fused the Australian and Chinese aspects of her identity that had so troubled her when she was young. She is looking both inwards, seeking self-knowledge, and outwards to the natural world – another Zen paradox, perhaps.

The poetic image of the moon reflected in the tiny sphere of a dewdrop was a metaphor for the state of meditation, a kind of effortless/effortful approach to enlightenment through which the individual can perceive the entirety of the universe. Lee’s body of work reveals her search for this desired state of wholeness that she describes as finding ‘one’s true north’.(7)

As Dōgen said of himself watching the moon:

‘Sky above, sky beneath, cloud self, water origin’.(8)

Notes

1. See the text relating to The Silence of Painters (1989) on the website of the Museum of Contemporary Art https://www.mca.com.au/artists-works/works/1995.191A-O/ [accessed 10.12.20]

2. Lee began to study Zen Buddhism in 1993, taking Jukai, the formal initiation into Zen Buddhism, in 1994. For more see Jane O’Sullivan, ‘Lindy Lee: The Original and the Copy’, Vault Issue 30, May/July 2020. https://www.sullivanstrumpf.com/assets/Uploads/VAULT-Issue-30-Feature-Lindy-Lee-compressed.pdf [accessed 9.12.20]

3. ‘A Conversation between Elizabeth Ann McGregor and Lindy Lee’, in Lindy Lee Moon in a Dewdrop, exhibition catalogue: Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2020. p. 17

4. Julie Ewington, ‘In Praise: Concerning Anne Ferran, Judith Wright and Lindy Lee’, Eyeline 84, 2016, available at https://www.sullivanstrumpf.com/assets/Uploads/Julie-Ferran-Wright-essay-for-Anthology-22-June-2017.pdf

5. For more information see the textual information produced for the exhibition, ‘The World of Scholar’s Rocks: Gardens, Studios and Paintings’ at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2000. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2000/world-of-scholars

6. Yokoi, Yūhō (with Daizen Victoria), Zen Master Dōgen: An Introduction with Selected Writings. New York: Weatherhill Inc., 1976

7. ‘A Conversation between Elizabeth Ann McGregor and Lindy Lee’, in Lindy Lee Moon in a Dewdrop, exhibition catalogue: Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2020. p. 21

8. In 1249 Dōgen wrote a poem for his portrait, a painting now known as the ‘Portrait of Dōgen Viewing the Moon’. For more see Kazuaki Tanahashi (ed), Moon in a Dewdrop: Writings of Zen Master Dōgen, San Francisco: North Point Press, 1985. This text has been digitised and is available at https://terebess.hu/zen/dogen/Moon-in-a-dewdrop.pdf