This piece is included in Ran Dian’s print magazine, issue 2 (Winter 2015–2016)

Zheng Bo is not a prolific artist. He maintains a certain distance from art circles, yet he has studied and practiced socially engaged art and social engagement for over a decade. When conversing with Zheng Bo, it is very difficult to draw any assumptions about his background based on his accent, behavior, or mindset; it is as if there are too many clues.

Zheng Bo was born in 1974, and grew up in Beijing. After graduating from high school, he was meant to study Physics at Peking University, but following a year of military training, he instead went to study abroad in the US, majoring in Computer Science and Art. After graduating in 1999, he went to Hong Kong and worked as a consultant until he tired of his job four years later, and resigned to study Artistic Creation at the Chinese University of Hong Kong as a graduate student. After receiving his Master’s degree in 2006, he went on to do his PhD in Visual Culture Studies at the University of Rochester in the US under the tutelage of Douglas Crimp. After that, he went on to teach socially engaged art at the China Academy of Fine Arts and the City University of Hong Kong.

Zheng has thus spent most of his adult life in the US and Hong Kong, but he remains a Mainlander at heart, because his early years were spent within China’s high-pressure, mechanized, anti-individualistic education system. He also received a year of military training prior to entering university. The artist has an intimate understanding of what it takes to construct an “outstanding, proper, and standard” member of the Chinese elite. Considering his later experience studying liberal academic environments in the US and Hong Kong where the social environments are more tolerant and equal, it should come as no surprise that the comparisons between these two sociopolitical climates are common motifs in his art.

In 2004, not long after he began studying at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Zheng made a video work entitled “Welcome to Hong Kong”. At the time, Hong Kong had recently opened up to tourists from the Mainland. The video introduced some of Hong Kong’s main attractions in the form of a guided tour—but two different versions of the narration were used. One version toed the official CCTV party line, lauding the “one country, two systems” policy while preaching prosperity and stability. The other version introduced the actual political and economic situation in Hong Kong following its return to China, and expressed the worries that citizens held for Hong Kong’s future.

Nowadays, this piece seems overly simplistic and superficial in terms of completeness, but it clearly indicates Zheng Bo’s interest in and sensitivity to politics and society at a time when he first began experimenting with art. This beginning was also influenced by contemporary art local to Hong Kong, and Hong Kong’s social environment. Zheng Bo was already very familiar with the PRC’s political propaganda, but the many years he spent in Hong Kong surely influenced him to a degree where listening to typical Party rhetoric would have been somewhat embarrassing for him. Hong Kong society takes pride in the freedom of speech and thought; when such propagandist rhetoric crosses over from the Mainland, its effect is tone deaf, intolerable. Zheng Bo’s work expresses the same anxiety felt by many Hong Kong artists at the time, an anxiety shared by young Hongkongers who were also aware of the PRC’s subtle message of assimilation, and feared the socio-political regression. However, Zheng Bo’s anxiety was a result of his identity as an individual inhabiting two different political environments.

《师华步(录像截屏),工作坊,双屏录像,6分钟,2013

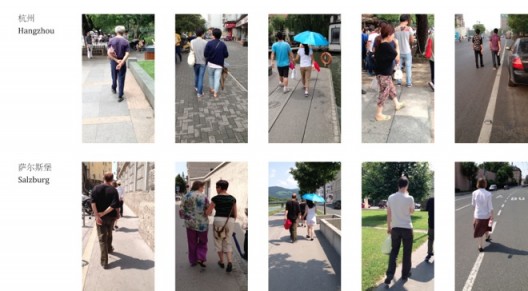

In 2013, Zheng created a humorous piece entitled “Walk Like Chinese” comprised of six videos teaching viewers how to walk like a Chinese person. In the artist’s statement, he wrote, “Before I forget how to walk like a Chinese person, I have created these educational videos for you and also for myself.” The artist follows pedestrians on the street in China, recording “classic” examples of Chinese style locomotion with his iPhone. Each style is prefaced with a title, including “bear step”, “dangling a cigarette”, “sunshade”, “hunched shoulders”, “in conversation”, and “a stroll”. The second part of the piece uses the video as instructional material, and documents the process of teaching a group of Austrians in Salzburg how to walk like a Chinese person. Interestingly, when seen from behind, this group of foreigners who have learned how to walk like a Chinese person indeed resemble a group of Chinese people. Compared with the coiled tension of “Welcome to Hong Kong”, Zheng here embeds his unease within the ridicule and mockery of the videos. Due to his many years of living between the Mainland, the US, and Hong Kong, he has gained a certain perspective on the Chinese, thereby obtaining a vague sense of their shared national characteristics. He has clearly come to the realization that society is made up of countless individuals, and that it is the sum of their individual interests, character, values, and ideology which determines society’s overall trajectory.

Ultimately, Zheng Bo is a professional student, staff member, and teacher. He does not detach himself from society in a manner typical of many artists; he cannot shut himself away for long periods of time on a whim, nor does he belong to a “community of artists” with its various distractions ranging from debates about art to subtle competition between members. He has chosen to distance himself from the commercial market, and engages in an artistic practice corresponding with his personal experience and rich academic background–a practice that is at once solitary and extremely social. Whether he is in the US or in Hong Kong, Zheng Bo is always a minority in the society he inhabits, which also explains why he is drawn to minority communities in his social engagement sand art. The concepts of “in groups”, “class”, and “community” lie at the core of his body of work.

Between 2004 and 2013, Zheng worked twice with the Filipino community in Hong Kong, creating “Happy Meal” and “Sing for Her”. In “Happy Meal” he invited five Filipino and Indonesian women to tell jokes, to help their employers understand their talents outside of housework. In “Sing for Her”, Zheng worked with a group of Filipinos to record them singing a popular Filipino song from the 1930s and 1940s alluding to the desire for the Philippines to achieve national independence, entitled “O Ilaw”. By singing this song, the artist helped bring attention to labor rights of Filipinos working in Hong Kong as well as their political aspirations. The piece also gave this group of individuals, who are largely invisible outside Hong Kong’s economic and political context, an opportunity to be the narrative object in an artistic and cultural setting.

《為伊唱》,參與性多媒體系統,尺寸可變,2013

《為伊唱》,參與性多媒體系統,尺寸可變,2013

《為伊唱》,參與性多媒體系統,尺寸可變,2013

Zheng Bo has categorized the many kinds of socially engaged art he has been studying and practicing over the years as “new public art”. This type of practice is closely interlinked with life; it is concerned with and actively participates in public issues. For this kind of art, works are manifest as community participation, involvement, and interaction rather than a purely individual form of expression. The artist is relegated to the role of “initiator” and “organizer”, forming a partnership with the viewer while remaining obscured by the piece itself. It is also difficult to circulate this type of art on the art market because its appearance seldom takes into account aesthetic considerations–such pieces are not a form of “fine art”. For example, the main content of “Sing for Her” is impossible to present in a gallery setting; it becomes meaningful to the participant during a process of interaction. Critics of “new public art” often mention over-emphasis on political objectives, but Zheng Bo balances grand themes on the oft-ignored minutiae of culture in everyday life. He believes deeper political significance can often be gleaned from such details. Indeed, there are no ultimate solutions for political issues. If this type of art can raise public awareness and encourage more people to engage in social reform, then such sociality itself will possess an aesthetic significance that transcends form, while also distinguishing new public art from social movements, and life itself. This is similar to the long-term project related to “weeds” that Zheng has expanded to several cities since 2013. The project analyzes and narrates the origins and characteristics of various wild plants in urban environments. By studying them as visual symbols and extending their meaning in the context of China’s process of modernization, the artist explores the relationship between plants and society and politics.

Since 2014, Zheng Bo has been running “A Wall” (www.awallproject.net)—a web platform for documenting and presenting new public art projects. The platform’s first stage encompassed six new public art projects from the Mainland, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. The nature of new public art means the medium is destined to be absent from circulation in art market platforms such as galleries or exhibitions; it is also difficult for new public art to enter museum collections. Thus, there is an urgent need to construct a public platform to collect, collate, and research new public art projects that have happened or are currently in progress.

Zheng Bo has named this project “A Wall”, constructing within the digital world a “wall” which could not exist in the material world, and “posting” these artists’ new public art projects on the wall. Zheng would like to see this project continue for the foreseeable future as a public, non-profit online database which helps expose more viewers and researchers to new public art. He envisions the project as a supplement to mainstream contemporary art, one which inhabits a space outside the logic of art production and consumption where the works will not be subject to power or capital, yet remain deeply embedded in society.

《住在上海的植物》,植物现场、网络课程、教育活动,上海市徐汇区,2013

《住在上海的植物》,植物现场、网络课程、教育活动,上海市徐汇区,2013

《住在上海的植物》,植物现场、网络课程、教育活动,上海市徐汇区,2013

《Weed Party》 (Leo Xu Projects 装置现场),野草,泥土,镜子,2015

[This piece was first published in #2 of Ran Dian magazine]