Paul Gladston charts the trajectory of Yu Youhan’s practice from his literati-inspired abstract works, to his political pop paintings to his fusion inspired landscapes — revealing new meanings behind his worth through in-depth interviews with the artist.

…“Diaspora” as a performative action (as a verb rather than as a noun) takes place necessarily in relation to three differing, though mutually interdependent, locations: the location of departure; the location of arrival; and the (desired) location of return ― which is always simultaneously (contemporaneously) the “actual” location of departure and, because of the ineluctable relativity of motion (parallax), another, imaginary/remembered, place. To travel diasporically is always to reach a(n end) point of no (effective) return (if only in retrospect): the traveler either never goes back in actuality to the location of departure (the “definitively” diasporic trajectory), or, upon actual return, experiences an irretrievably disjunctive slippage between place and imagination/memory (qualified only, perhaps, by the interventions of reconstructive memory). In all eventualities, the diasporic traveler is not so much permanently displaced as s/he is dislocated (that is to say, set out of joint) from — while still being (imaginatively) connected to — the location of departure (and by extension that of a desired/imagined return). The journey of the diasporic traveler traces an endless circuit, one that continually overwrites its own beginnings, middles, and ends (insofar as they can be differentiated)…differences inscribed in an eternal return of the same that may or may not be local and/or regional as well as trans-national.

[…] Yu Youhan: There’s a saying in China which is “luo ye gui gen.” This means that you’re born in one place and no matter where you go later on when you get old you will always return to the place where you were born. In other words, it means you start from a certain point and get back to that point in the end. […] Chinese aesthetic points of view change as the positions of the viewer change. A typical example of this is the Chinese garden. When you are in a Chinese garden, what you see changes as you move through the space. When you are in a Western garden the totality of the garden is emphasized. […] I don’t like to use the same style to make paintings all the time. Some artists stick to one style and go deeper and deeper into that style, whereas for myself, I prefer to “shoot a gun and change my position.” There were so many different kinds of Western art in front of us during the 1980s. I was so curious to see what would happen if I tried different types of painting rather than being limited to one style. As I said earlier, I was an art teacher at the time, teaching landscape and scenery painting. I was also very interested in abstraction. So it was my personal interest to get to know different kinds of Western painting styles. I just followed my own feelings. (1) […]

Yu Youhan was born in Shanghai in 1943 during the time of the city’s occupation by invading Japanese forces and before the end of Euro-American colonialist/imperialist dominance in China in 1949. Since his graduation from the Central Academy of Art and Design in Beijing ― one of the very few higher education institutions to have remained open during the Cultural Revolution ― in 1973, Yu has continued to live and work in and around Shanghai. His early development and mature career as a painter has therefore traversed a period of significant upheaval and change in Shanghai that extends from the tumult of the Cultural Revolution to the prodigious socio-economic and political changes of the post-Maoist period.

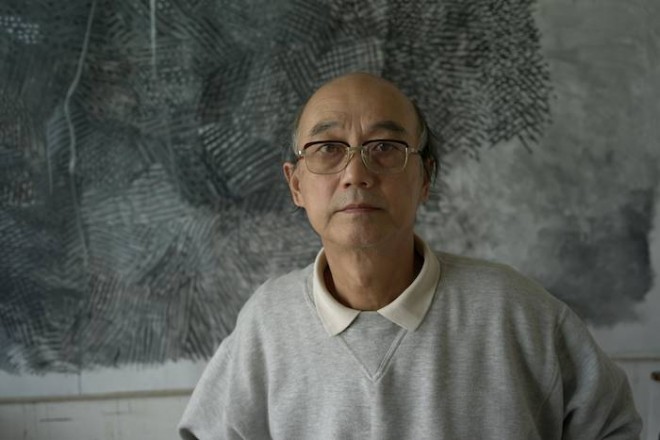

余友涵 (摄影: 葛思缔Paul Gladston)

[…] After the founding of New China in 1949, Shanghai rapidly became a center for both heavy industry and radical leftist politics (Jiang Qing and the other members of the Gang of established a political base in Shanghai during the Cultural Revolution). In spite of the wider tumult initiated by the Cultural Revolution, during the 1960s and into the second half of the 1970s, Shanghai’s social structures remained relatively stable and its industrial productivity high. Shanghai’s importance as a stable source of tax revenues for China’s central government, as well as continuing concerns in Beijing about the city’s cosmopolitan past and enduring political radicalism, meant that it was initially excluded from the economic and social changes initiated by Deng Xiaoping’s Opening and Reform in 1978/1979. Economic and social reforms only began to take hold fully in Shanghai in the early 1990s after Deng’s Southern Tour of 1992. Since then Shanghai has grown exponentially to become the largest city by population in the PRC as well as the busiest container port in the world. […]

[…] Yu Youhan: […] I have always paid close attention to the changes that have taken place as part of the development of my country. Chinese society became quite corrupt during the 1980s and I wanted to address that in my painting. Initially, my abstract paintings were only for a small group of people ― a kind of bourgeoisie living in an ivory tower. This was all right to begin with, because I made my early abstract paintings more out of personal interests and preferences. There were no public exhibitions of those paintings. However, later on, I felt that it was necessary to change my approach toward painting.(2) […]

Following his graduation, Yu took up a position as a teacher close to Shanghai, where he gave classes in Western drawing and painting techniques and produced paintings similar in style to those of Maurice Utrillo and Henri Matisse [plate 1] Contrary to stereotyping views of the supposedly monolithic nature of artistic production in the PRC during the Cultural Revolution, the open adoption of such approaches became increasingly possible there from 1973 onwards.

余友涵, 《华亭路》,油画,1973

[…] In Shanghai, deviations from the artistic norms of the Maoist period took place against the background of previous artistic reforms initiated during the late-nineteenth and early twentieth century by the Shanghai School of painters. Members of the Shanghai School sought to counter the entrenched conservatism of traditional artistic practice in China (and especially that of Beijing) by developing modern free-form, though still recognizably indigenous, approaches to Chinese painting — a move that contributed strongly to the contestation of reformist and conservative values known as the Jingpai versus Haipai (Beijing versus Shanghai School) debate. […]

At the end of the 1970s, in the context of the more liberal political climate ushered in by Deng’s reforms, Yu gradually abandoned his early representational style to make a series of abstract paintings that, from the mid 1980s, brought stylistic influences from the work of Piet Mondrian together with traditional Chinese shanshui and shuimo brush painting techniques through the repeated use of a circular compositional format [plate 2].

余友涵, 《1986-16》,绘画, 109 x 97 cm, 1986

[…] Yu Youhan: I started to make abstract paintings using a circle (yuan) motif in 1984/1985.(3)

In an unpublished statement titled “Starting from Composition” (1985), Yu states that he chose the circle motif for his abstract paintings, “because the circle is stable, representing the beginning and the end of all things and symbolizes both a moment and an eternity. The circle represents a repeating circular movement; it also hints at the movement of expansion and contraction. Thus, a circle can symbolize grandness with compatibility, tolerance, rationality and peace.” Yu also asserts that, “in the painting, I tried to unite all the opposing elements, such as modesty and wisdom, tranquility and vividness, eternity and levity, something and nothing.”(4) […]

Yu’s early abstract style grew out of a personal desire for self-cultivation as well as to develop a spontaneous and calming aesthetic commensurate with that associated traditionally with Chinese scholar-gentry/literati painting. Yu’s early abstract works became increasingly well known within the indigenous Chinese art world as part of the artistic movement known as the ’85 New Wave, leading to their inclusion in a number of major exhibitions of modern art (xiandai yishu) in China during the second half of the 1980s, including the era-defining China/Avant-Garde exhibition at the National Art Museum in Beijing in 1989.

余友涵, 《世界是你们的》,丙烯,117 x 158 cm, 1994

In 1988 Yu began to make “Pop” paintings that were influenced directly by the work of Andy Warhol and Richard Hamilton. These works would eventually come to be seen alongside formally similar works by Wang Guangyi and in light of the seminal survey exhibition of contemporary Chinese art, “China’s New Art, Post ‘89” as part of the movement known internationally as Political Pop (zhengzhi bopu) [plate 3]. So-called “Political Pop” paintings, which often combine images of Mao Zedong with symbolic and decorative motifs culled from Chinese and Western popular culture, were interpreted both with China and internationally as deconstructive interventions on the authoritarian politics not only of the Cultural Revolution but also, by association, post-Maoist China.(5) Yu’s own interpretation of his “Pop” paintings is however, in political terms at least, much less clear-cut:

When I painted the Mao series, though I cherished the Maoist period, I also held more reflective and critical feelings about that period, too. So, some paintings, which may appear to be a form of bohemian realist art, didn’t express optimistic feelings at all. Instead, they were trying to reveal feelings about the betrayal of socialism. I think the Mao series of Pop paintings should belong to the history of China’s folk or historical paintings. In these paintings, the background colors are very bright. But, if you look carefully, there are unstable elements in the background suggesting that disaster may take place at any time. As for my feelings towards Mao, though I no longer admire him as I used to during the Cultural Revolution, I don’t think we should deny him totally. And I don’t think Western propaganda about Mao is right either. I think every leader would like to lead their country toward a better future.(6)

In the early 1990s Yu produced variations on his Pop paintings involving contrasting juxtapositions of Western and Chinese pictorial elements. During the 1990s Yu then embarked on a series of landscape paintings that combine Western and Chinese stylistic elements into a single pictorial format [plate 4]. Yu’s intention in making these landscape paintings was to arrive at a synthetic reconciliation of Western and Chinese painting styles ― among them those of Paul Cézanne and Chinese shanshui paintings. The extent to which Yu’s later landscape paintings arrive resolutely at such a synthesis is, however, open to question.

余友涵, 《屋顶上的维吾尔姑娘》

[…] Paul Gladston: Are these paintings yet another allegory of contemporaneous events; this time the difficulties of assimilating “Western” modernity while maintaining some sort of a vernacular Chinese cultural identity as part of the process of opening-up and reform? Your paintings would appear to be the result of a struggle to bring Western and Chinese resources together as a novel means of representing the Chinese landscape.

Yu Youhan: Do you mean that I didn’t find the connecting point?

Paul Gladston: I don’t mean to suggest that the paintings aren’t successful. It’s just that the relationship between the differing styles isn’t fully resolved.

Yu Youhan: I hoped that Oriental elements and Western elements had been connected quite well. However, if one looks at it again professionally, there might still be some difficulties in combining Western and Chinese elements.

Paul Gladston: Well, it would be very difficult, if not impossible, to bring them together seamlessly. What intrigues me here is that there seems to be an unresolved tension in your landscapes between Western and Chinese landscape painting styles. It’s interesting to me precisely because the relationship between the two doesn’t appear to have been fully resolved. This leaves the possibility of a dynamic and open-ended relationship between differing cultural points of view, one in which each continues to re-contextualize and re-motivate the other.

Yu Youhan: I understand what you mean. Some art works incorporate three totally inharmonious elements into one piece of work. They don’t try to harmonize them. Instead, they try to reveal their inharmonious characteristics. I’m not sure yet which standpoint I hold. It is still one thing I’m working on, to mix Eastern and Western elements perfectly.(7) […]

In recent years, Yu has returned to his earlier abstract style of painting [Plate 5].

余友涵, 《2011.5》, 绘画/布上丙烯, 172 x 142 cm, 2011

[…] Paul Gladston: In coming full circle stylistically, do you think that you have returned to exactly the same place, or do you think that you have arrived somewhere else?

Yu Youhan: The paintings are not exactly the same. I just followed nature. The essence of a person doesn’t change. So no matter whether I’m making an abstract painting or a landscape or a portrait, the essence is still the same; they express the same perspective or habit. When you get older, it’s not as easy to change your aesthetic view points. So I’m not a revolutionary in art. I follow my interests and nature. When my interests change, I change.(8) […]

Yu Youhan’s mature development as a painter after 1979 has described a near-circular trajectory. It has undergone a sequence of apparently sweeping formal transformations before arriving (almost, but not quite) back at its initial point of departure; an outcome of “diaspora” not as a noun but as a verb….

(1) Gladston, Paul (2011), Contemporary Art in Shanghai: Conversations with Seven Chinese Artists, Hong Kong: Timezone 8 / Blue Kingfisher, 30-31.

(2) Ibid, 29.

(3) Ibid, 28.

(4) For an English translation of Yu’s statement, see Fei, Dawei, ed. 2007, ’85 New-Wave: The Birth of Contemporary Chinese Art, Beijing: Ullens Centre for Contemporary Chinese Art, 60.

(5) See, for example, Li, Xianting (1992) “Apathy and Deconstruction in Post-’89 Art: Analyzing the Trends of ‘Cynical Realism’ and ‘Political Pop’” in Wu, Hung (ed.) (2010), Contemporary Chinese Art: Primary Documents, New York City: The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 157-166.

(6) Gladston, Contemporary Art in Shanghai, 32.

(7) Ibid, 37.

(8) Ibid, 38-39.