“So, are we starting?”

“It’ll just be a casual conversation; don’t be nervous.”

“Really, it’s hard for me to feel nervous.”

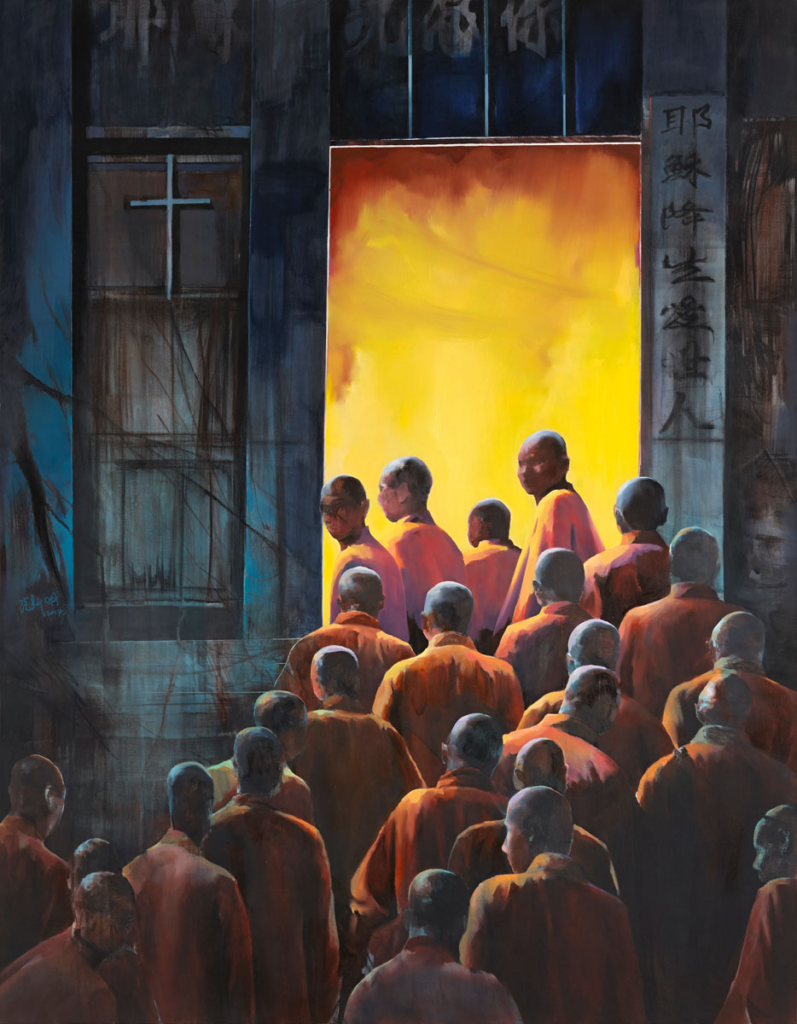

Seated before me in the parlor of Edouard Malingue Gallery is young Chinese artist Cui Xinming. The artist is not yet 30 years old; his newest works—a series of large-scale oil paintings—are on show in the next room in an exhibition entitled “Journey to the East”. The Edouard Malingue Gallery also held an individual show for Cui during last year’s Art Basel Hong Kong—no doubt a huge show of support for the fledgling artist. The themes and subjects of the pieces in this year’s exhibition do not differ much from a year ago: the same mysterious amalgamation of blurred figures and crowds, night-time village scenes, temples, and thriving flora continues to burst forth in the artist’s wild brushstrokes and vivid use of color. In comparison, the contrasts in the new paintings are more intense; the brushstrokes firmer and more assured. Yet they have inherited the same drama, gravitas, and sense of the literary from his previous works. While they elicit an indescribable feeling of unease and anxiety in the viewer, Cui’s paintings also provide a narrow glimmer of solace.

Compared to the majority of young artists, Cui Xinming’s career has been relatively successful, but this 2012 graduate from the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts hasn’t always had an easy path in his studies. Originally from Shandong Province, Cui enrolled in a Normal University as an oil painting major intending to teach art, but in his third year, he found that his school was no longer able to satisfy his thirst for more: his instructors only possessed a smattering of knowledge and focused all of their classes on technical perfection. Upon graduation, Cui decided to continue painting instead of seeking employment. He heard from a friend that the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts provided an open environment for artists. Cui applied successfully to the Academy, despite the difficulty of getting into the oil painting major. His three years as a graduate student have become a source of motivation whenever he is faced with a challenge. In describing the creative frenzy of those three years of intense, focused study, the artist says,“I didn’t even know who the female students in our class were.” He cloistered himself in the workroom, at times even suffering from migraines due to the oil paint fumes. “I was extremely focused, and life was simple. I only wanted to make my paintings better. Every week, a group of my friends would get together for some beers, and everyone talked about their new paintings. It was a simple way to live, and I loved it. Of course, as my career began to develop, this simplicity became more and more complex. So I often reminisce about the single-minded focus of that time.”

In his transition from a Normal University idolizing Freud and Monet to a contemporary art environment, Cui was suddenly exposed to massive volumes of complex information. He found himself liking dozens of styles every day, which destined him for a painful period of filtering through these influences. The cards were reshuffled, and he had to begin anew: “Whenever I thought of a new approach, I discovered someone else had already done it.” It wasn’t until the latter half of 2010 that he came to a turning point, and he was able to see the path ahead—regardless of the style or concept employed, he found the key was in the aptness of expression. From this point, Cui began to paint his innermost feelings. With this breakthrough, his creativity found release. Bit by bit, the artist magnified these feelings, and as they grew, so the scale of his paintings increased from four meters to five, and beyond. Gradually, he began to win some awards and earned the approval of his instructors. Eventually, he received the Luo Zhongli scholarship, and the scholarship’s sponsor, Mr. Qiu Haoran, recommended him to many art critics, giving him much encouragement. While doing an exhibition in Shenzhen in autumn 2012, Qiu Haoran sent some of Cui’s paintings to Edouard Malingue Gallery, which in turn led to his solo show during the 2013 Art Basel. Cui Xinming’s friends tell him, “Every time I visit you in your studio, you’ve got your mask on, and you’re standing on a bench painting.” After Art Basel, Cui’s career was on track, and his working environment improved as well, helping him focus more on his creative work.

崔新明,《孔子故里 II》,布面混合材料,120 x 150 cm,2014

崔新明,《Don’t hurt me I》,布面混合材料,140 x 180 cm,2014

展览现场

展览现场

Changes in the visual language of paintings are intimately linked with the artist’s own growth. Cui makes the following analogy: “A person who is hostile towards society might one day find himself in a position of weakness in a public setting, and if someone should help him when he is in that situation, his attitude towards society would inevitably change. Creation works along similar lines; when you read a certain passage, hear a rhythm, see someone, some painting, or some piece of news, your ideas are affected by these things. This then affects your expression, changes the content you focus on, and the intensity and scale of which techniques you choose.” All of these are natural changes that occur depending on the situation.

In this era of rapid consumption, the ability to filter information has become especially crucial to creators. Cui Xinming has begun a reexamination of the information channels he is exposed to; by filtering out fragmented information, he has restructured his life so that the majority of his time is either spent thinking or reading literature, art criticism, art history, and art books. For example, he questions himself— “What is painting, and what should painting now be providing?”, and reflects on how to balance elements of painting to achieve the results he desires. Though he hasn’t found the answers to these questions, he has made marked progress since last year. His paintings are freer, and there is a greater sense of ease in way he processes his images. They have broken free of the limitations of the visual, and by adjusting color, composition, and brush strokes, his paintings are more clearly delineated, and their colors form a better contrast. Additionally, this year’s paintings have more patterns—physical elements which give the viewer a sense of space—in other words, they have symbolic meaning, and represent a type of energy field. In breaking free of a purely technical form of expression, his paintings gain a sense of the random, making them more subtle and opaque. This is precisely how Cui Xinming wants his paintings affect their viewers.

Meanwhile, he continues to seek out an even better method of expression by constantly fragmenting and reconstructing elements of painting. Often appearing in his paintings are everyday elements from the artist’s past such as village housing structures, patterns of interpersonal relationships, statues of idols, and temples. However, the rich political and religious subtexts hidden in his work often lend them a quality of simulated, fictional reality. In the half light of “nostalgia”, experiences, environments, and situations are interwoven with traditional village structures to form a massive labyrinth—an earthy and primitive social structure exposed within the “global village”. In this state of confusion, reality seems more like a dream—a sentiment clearly expressed in the titles of his paintings—“Sleepwalker”, “Empire is a Dream”, and “Night Owl”.

In the way people use journals, photographs, and late nights as markers for their memory, helping them remember the fragments and scenes linked together by text and images, Cui Xinming hopes his paintings will become markers reminding certain viewers of bygone times. When they see his paintings, Cui Xinming wants them to recall the amorphous qualities of an era. He places before their eyes these undocumented memories, alienated through art.

展览现场

崔新明,《帝國是一場夢》,布面油画,180 x 150 cm,2013

崔新明,《夜巡》,布面油画,140 x 180 cm,2014

崔新明,《夢遊症5號》,布面油画,150 x 200 cm,2014