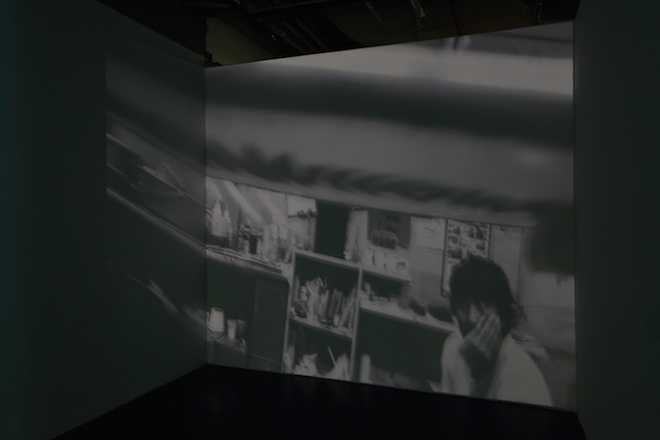

It is easy to mistake the medium for the subject, conflating art and artist, and vice versa. Self-portraits particularly invite lazy interpretation, especially when they are beguiling clones of school dreams and fashion magazines. Cui Xiuwen’s “portraits” though are only ostensibly about her. She is her own medium but the medium is not the subject, only the starting point. She is one of her media. Her video “Lady’s Room” (2000) offers us a key. It is not a foundation work or even representative (the very reason it helps unlock interpretation). It is a secret recording of the women’s bathroom in a large Beijing nightclub, specifically the mirror behind the washbasins, reflecting the young women as they come and go. Apparently most are prostitutes. They gossip, arrange appointments, discuss transactions and count money. It is a literal reflection of a certain time and place, a portrait but also a social critique and satire. There is a superficial prurient element, particularly for men, but that is part of its seduction. It is essentially about women, and time, and how they are defined by and define themselves within a quasi-public-private space. The personal is political.

崔岫闻 “琴瑟” 金丝楠木、丙烯 (image courtesy the artist and SGA)

Cui Xiuwen’s long series of painting and photography comprising Matrix-like clones of her as pubescent schoolgirls alienated me. Clearly they were never just about her. Each portrait refracted the experiences of a multitude of young women of her generation in China. The problem however was when the depictions became just another multitude. Yet even these were about space (often historically important locations, such as the Forbidden Palace) and time, or rather the (female) individual situated within it (rarely does Cui depict men). The red neckerchief worn by the girls was open to a variety of interpretations, familial, menstrual, communist and so on.

崔岫闻 “哪里 No.2″ 三屏视频装置, 尺寸可变

(image courtesy the artist and SGA)

Woman, girls—the ambiguity of maturity is important—are depicted as interchangeable functionaries within a system: their function being subjects of instruction: school students. The schoolgirl is problematic, typical but also foreign and fetishized. Is she emerging as a social object in play or at play? —A risk or at risk? —Compliant or disruptive? Their multitude suggests a latent power, perhaps as yet even subjectively unrealized. Within that multitude is the experience of time: every woman’s time, circadian and sexual rhythms but also epochal experiences, and the personal reckoning with each. Buddhism, a religion founded upon the notion of reincarnation and whose very practice marks time in numerous ways, is important to Cui’s work too. It is a belief system and a philosophy but its observation is private; that is, confined to the space of the individual adherent. Cui is certainly not the only artist in China to demonstrate a personal adherence to Buddhism (others include Zhang Huan, Li Hui and Shi Jing) but her approach, unlike her male colleagues, is personal rather than performative. This can be seen in her new works, abstract-like paintings and film installations that mark the most radical formal shift of any Chinese artist in recent years. Yet the underlying theme remains the same: the experience of a woman—women—in a certain time and space.

“I chose ‘reincarnation’ as the exhibition title in the hope to express the idea of transcending reincarnation and liberation, and to access a new and dematerialized status of life.“—interview with Josef Ng

The new body of work was first exhibited at the Shanghai Gallery of Art, located on the famous Bund overlooking the vastness of corporate Pudong.

崔岫闻, “轮回” 烤漆铝合金、布面丙烯.

(image courtesy the artist and SGA)

These works seem to be products of this new urban landscape—instances of its crystallization. Her strident pitch of verticals speaks to this new China. The visual hum and frequency of the chords, which reference the hues of Cui’s previous work, including the juxtaposition of red, is distracting and even claustrophobic. If cubism was concerned about the simultaneity of depictions of time and space, this is about their excess; an overabundance of impressions digitized into “lines” of code, the visual-physical impact, restrictive, relentless and giddy. Reincarnation is a matrix but it is necessarily also destructive.

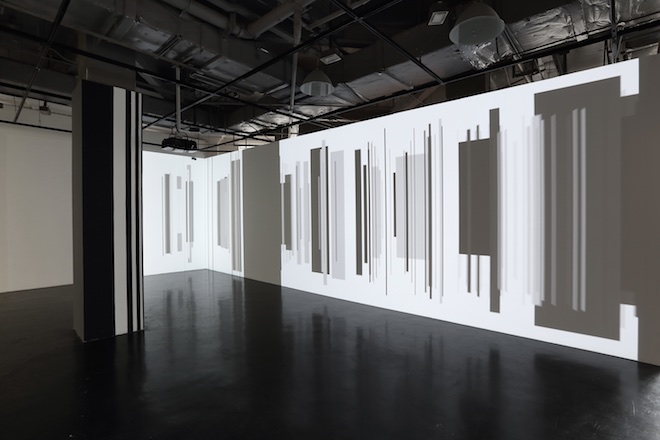

The video installation is most illustrative of how the images are constructed. Verticals of different heights, breadths and hues of grey-to-black seem to advance and retreat, a mirage of a metropolitan avenue, the individual passing through a steep valley of glass, concrete and steel. Occasionally a red, almost-vertical line scans across the tableau. This is one “projection” of meaning. The “lines” are open to multiple meanings. They can represent individuals or one individual in different spaces or in different times in the one space. Identity itself is shifting, fluid. There are paintings—acrylics on canvas and varnish on metal. Some include pieces of wood, connecting the modern and traditional worlds, artifice and nature (“No.7 Qin”). The optical-play is reminiscent of techniques employed by certain Op Art artists like Victor Vasarely (1906-1997) but the shifting verticals and horizontals also speaks to a fragmentation of modernist unity and grids, typified (perhaps unfairly) by the work of Mondrian. One only has to look up at the Shanghai “Boogie Woogie” that agitates in fits outside and in myriad renewed metropolises throughout China, as much as anywhere else. Cui’s response, which might be termed feminine, is not to compete but to measure, not to define but to explicate, to process, to seek a rebirth.

References

Moving Image in China: 1988-2011, Minsheng Art Museum, pp.370-373.

Unpublished interview with Josef Ng, curator and director of SGA.