text by Wang Ziyun, translated by Yang Tiange

Buddhist Youths: United Collective Indifference

Li Shuang, Mountain River Jump!, NHK, Jovana Reisinger, Wang Yuyu, Yang Yuanyuan, Payne Zhu

Curators: Yasemin Keskintepe, Yang Tiange

Grey Box Space, Goethe Institut Beijing (Originality Square, 798 Art District,2 Jiuxianqiao Road Chaoyang District, Beijing) 2020

“Buddhist Youths: United Collective Indifference” centered on the label of “Buddhist youths” and other expressions reflecting young people’s ways of existence today. As a fashionable subcultural phenomenon, “Buddhist Youth” designates a general way of life that is not classifiable by solely any regional or urban standard. On the one hand, most of them are city-dwellers who are deeply engaged in the experience of a fast-changing China. On the other, the exhibition provides an excellent portrait of their lifestyle as indulging themselves in the virtual world and staying disengaged from reality.

I have sympathy for this social phenomenon, but not in support of the self-blame and self-abandonment that it implies. In fact, for the curators of the show, Buddhist youths in contemporary society could mean both active withdrawal and passive resistance. The curators of the exhibition also use the phenomenon of Buddhist youths as the start of this narrative and as a response to the reality, while at the same time emphasizing the attitude of “indifference”. So, what the “Buddhist-style” connects and corresponds to is not entirely the works and status of “lives of artists” but their reflections upon the reality in which they are engaged.

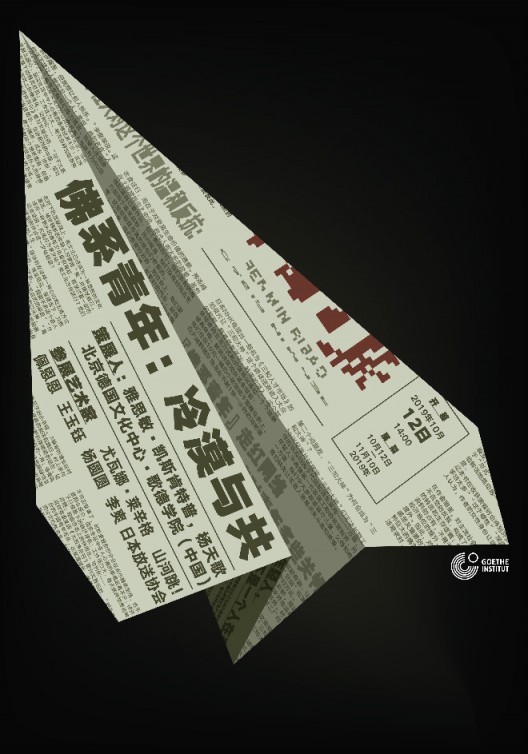

The originally narrow space of the Goethe Institut’s Grey Box in 798 was rearranged in a fashion that made it look like a noisy guest room. Outside, the audience could read various national or international press remarks on this group of artists, be it praise or critique. At the entrance, the documentary by NHK, the Japanese broadcaster, on the hopeless but unrestrained life of the “Sanhe Gods” and the life in poverty of those who frequent the job market looking for a temporary job, was played non-stop. The documentary about young part-time workers in the Pearl River Delta region, along with another work in the exhibition, Mad Girls Don’t Cry, points to feelings of powerless resulting from class fixation in the cities. The protagonists in both movies are presented as victims of the oppression of all kinds of standards and measurements imposed by society, to which their indifference forms a defensive armor.

The exhibition was organized into two dimensions. The first dimension represented mobile phone games, fortune-telling, and cloud recording/deletion, each corresponding to the works of three artists: Payne Zhu’s Ladder System (2018), Mountain River Jump!’s Red Eyes-2 (2019), and Li Shuang’s If Only the Cloud Knows (2005-2018). Viewed from the spatial context, mode of cognition, and the attitude of individuals towards data, about which these works were concerned, we may recognize a certain exploration and criticism of the Buddhist-style realities. Payne Zhu’s perspective aimed at excavating the evaluation system constructed by online computer games, especially its ways to dominate capital and humanity, and expose its ridiculousness by means of a “field study” on the internet. The group Mountain River Jump!, through its exploitation and deconstruction of the folklore faith in fortune-telling, rewrote the image of the woman in historical and legendary stories so as to react against the oppressed and negligible importance of women in the current system of rights. Li Shuang’s If Only the Cloud Knows abandoned identity and memory as defined by data, leaving personal photos in the database open to the audience to interfere with, who might dispose of the images at will, deleting them or leaving a comment. Behind her transfer of personal image data on the “cloud” to the audience, we may sense her hidden attempt to test the uncontrollable humanity in the virtual network. From the three works mentioned above, we may find out that none of them were satisfied with the appearance of the Buddhist-style reality; all of them tried to reflect on the value system and individual choices behind the phenomenon.

For the second dimension, the traces of disappointment and affective life in the cities constitute the main line of works such as Luka Yuanyuan Yang’s In-Between Places (2012), Wang Yuyu’s Multiple Narratives (2018) and Jovana Reisinger’s Mad Girls Don’t Cry (2018). Equipped with serious but sympathetic perspectives, the three artists delve into public space, memory space, and the space of personal emotions of the cities to rearrange the relationship between images and narratives. Like a wanderer, Yang Yuanyuan was obsessed with the milieu around her, such as parks, squares, aquaria, and shopping malls. Wang Yuyu stripped the narrative from Antonioni’s film Eclipse and replaced it with a new formal relationship of images. Jovana’s film recorded, with a certain sarcasm, the perplexed life experience of young German artists in a foreign country.

It is not difficult to infer that the intention of this exhibition is to discuss the status of life of Eastern and Western youths in light of the concept of the “Buddhist youth”. If there’s some sort of unity and particularity with regard to the region that we know as East Asia, the most remarkable proof is actually the inventions of very vivid terms in this densely populated area, fueled by the rise of a secular society in the cyberspace. The term “Buddhist youths” was born in this context of social change and became popular in various kinds of circumstances. The appearance of terms such as Otaku, Smart, and Diaosi, should be explained by the social roots that make the terms a representation of a phenomenon, a group of people, and a complex of emotions. Given the fact that popular Internet expressions replace themselves at a rather rapid pace, emotional experiences may also cunningly find different language habitats. This often happens in history; one may refer to the protest of the hippies, the disdain of this world shown by the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, and the cynicism of Diogenes. The only difference, however, is that apart from the same subtle emotions, it is hard for us to capture the direction of the force of the Buddhist youths. If we really need to find it out, we may best say that as long as there is the individual, oppressed by reality and the difficulty in expressing their emotions, this passive way of resistance will inevitably reappear.