“What comes after the apocalypse? Another apocalypse.” Nadim Abbas, the closest Hong Kong has come to a homegrown hero on the international art scene, has come to frame his practice as a Nietzschean eternal return— albeit with an element of the Hollywood post-apocalyptic disaster film mixed in. As an artist, he is more accustomed to working outside of the gallery space than within its idealistic confines: his major projects over the past year have taken place in an architecture office (“Satellites of ⁂” at CL3 Architects in the Hong Kong Art Centre), a luxury goods store (“Tetraphilia” at Third Floor Hermès on Orchard Road in Singapore), an art fair booth (“Zone 1″ at the Armory Show China Focus in New York) and now, coinciding with Art Basel in Hong Kong, a cocktail bar produced with the Absolut Art Bureau (“Apocalypse Postponed”). For this upcoming commission, Abbas has constructed a bunker seemingly suspended in mid-air, an architecture of thick sandbag walls perched on the 17th floor of a new office building in the heart of the city. Aficionados will drink cocktails from rice bowls and blood bags served by mute dancers while watching animations of rice weevils crawling over faces, among other things…. The artist had initially hoped to introduce a functioning ecosystem of weevils to the environment, but—fortunately for the bar’s branding efforts—weather intervened, and instead of the real thing, he ends up with many thousands of images propagating across the space, not only in animations but also printed all over the sandbags that make up the bones of the place.

While so much of Abbas’s work as an artist is about the practice of looking, asking his viewer to stand back and create critical distance in order to examine their context, this particular project demands immediate immersion. This immersion, while it does align the bar more closely with design than installation art, creates a perpetual temporality of the present in which the end of the world is constantly deferred and yet repeated, like an apocalyptic blockbuster that one plays only to rewind and begin again. An avid science fiction fan, Abbas positions this sensibility in the vocabulary of Philip K. Dick as a self-replicating reality in which visitors become stuck. The design connection is highly appropriate here, as it was initially an investigation into the design industry that led the artist to his interest in the connections between domesticity and war—to be precise, it was the website of iRobot, manufacturer of both the robot vacuum known as the Roomba and a wide range of defense industry autonomous vehicles.

With the Absolut Art Bar, however, design is no longer merely a theme; here, Abbas himself is implicated in the design process, and the question of inflicting violence, however subtle, is no longer so remote, as he finds himself charged with people instead of robots and images. While the specific iconography of “Apocalypse Postponed” is new, its components are strikingly modular and have evolved out of a broader set that has been in play in the artist’s work for several years. His rice weevils, for instance, appear to be new manifestations of the sexually-transmitted diseases with which his work has recently been concerned, and the sandbags as further developments of the concrete sculptures he has been working with. Both are terms in a dialectic play of virility and defense.

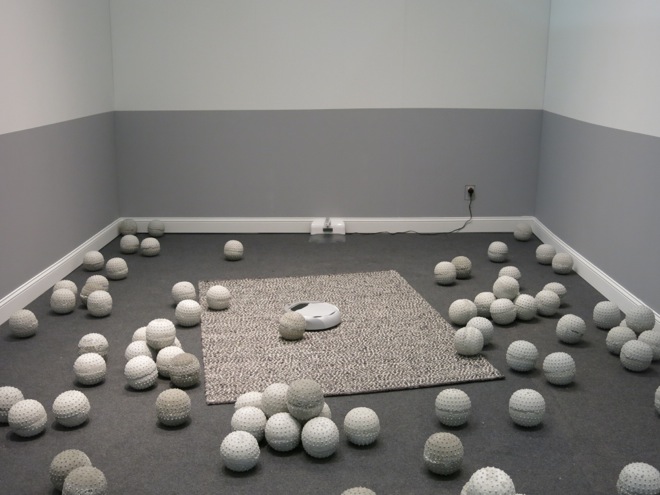

This connection between domestic cleanliness and international warfare is most fully developed in “Zone 1″ (2014), an installation very much site-specific to an art fair booth in which a robot vacuum cleans the booth carpet, constrained by and constantly running into a large number of spiky concrete balls. As much as he is struck by the technology fundamentally shared between drone warfare and housework, the artist also locates this shared design in the uncanny nature of interacting with such a simple robot, which he interprets as a broader metaphor for artificial intelligence and things to come in general. Domestic hygiene is tied up with these questions on a very basic level. Abbas chooses a light grey vacuum nearly camouflaged against a rug positioned over the default institutional carpet of the space, a nod to battleship aesthetics and, ultimately, stealth tactics. Asserting invisibility and yet roving like a stumbling drunk, this high-grade technology manages to be completely controlled by concrete objects smaller than a basketball, themselves artifacts of the artist’s interest in molecular structures because of the carefully constructed pattern that they form. As a project, the installation successfully diverts attention away from the typical visual economy of the art fair, which maintains interest strictly at eye level. On this level, Abbas’s work does not always travel well, and one could hardly imagine inserting a piece like this one in a different context; he works to architecture and environment to a fault.

These lines of thinking were first developed in “Satellite of ⁂,” the project I organized with Nadim Abbas in 2013. Occupying the lobby of an architectural firm in a Hong Kong office building, the installation is relatively tight but complex in its allusions: there is a hanging photograph of a rocket launch that can only be viewed clearly with paper 3D glasses, its exhaust surrounded by plants with yellow-flecked leaves (known in Cantonese as “golden shower”); there is a small transparent print of a galaxy on an X-ray viewer; there are four animations of rotating molecules depicting the four incurable STDs on upward-facing old-fashioned video monitors on rolling dollies; and there are dozens of concrete balls identical to those that would later appear in New York, stacked on top of and adjacent to tiny square mattresses. While Abbas continues working with his pet subjects—principally space travel and kitsch—the thematic focus in this project is on the tension between the sentimental and the clinical, working for the first time primarily in terms of affect rather than experience. The STD is the perfect confluence of the hospital and Platonic love, and the satellites that orbit around and are launched from the phallic rocket ship simultaneously reference the cosmic and the molecular. Strategies like visually homology work particularly effectively for Abbas given his interest in the cliche, and mirrored structures between the massive and microscopic, technological and biological are evident in almost all of his recent work. All of this, of course, is sublimated, as the subconscious is very much the artist’s favorite place to store things. For him, perversity lies in the eye of the viewer: the obscene remains outside the scene.

Exhibitions like these become legible almost entirely on a semiotic level, as the viewer locates and actively plots connections between images, stories and forms. Abbas, however, empathizes primarily with the concept of prosthetic vision or machine vision—ways of sensing and understanding that are foreign to human vision, hence the play of visibility and invisibility with something as seemingly simple as a vacuum cleaner or a 3D photograph. He first became interested in questions like these with early installations that played with the situated nature of perspective and vision, and later expanded these experiments to consider the “tourist gaze” in the ongoing series “Cataract,” which looked, among other things, to the nearly identical photographs taken by visitors to scenic places like Iguazu Falls. By the time he arrived at Afternoon in Utopia and P/120503-001 (both 2012), which use installation and photography, respectively, to realize the surfaces of other planets in our solar system, he had already latched on to the idea of machine vision in a much more rigorous way, albeit in a manufactured or fantastic sense: in the former he uses sand and light to recall the surface of Mars, while in the latter he sculpted, photographed, and then stitched images together to create a lunar landscape. In both cases he employs a striking confluence of the alien and the banal, the distinction between these two categories often as simple as the title, or the basic knowledge to contextualize and reframe the image at hand. Of course, even more so, it is the special case in which the alien becomes banal, or the banal becomes alien, that Abbas so revels in revealing.

“Satellite of ⁂,” of course, is titled after the Lou Reed song “Satellite of Love”; the running joke is that the artist must have sublimated the “love” away. It is, however, this willingness to confuse the semiotic or literary register with the scientific or mechanical that makes Nadim Abbas’s voice so unique. He asks that we listen a little bit more closely to the lyrics of the song: a man eats a TV dinner alone, fantasizing about an ex-lover sleeping with other men. Love, at a remove, becomes platonic. In a sense, this jibes with Abbas’s other major influence behind the exhibition: a website that hosts short animations using pure mathematics to computationally make visible phenomena that would be invisible to any sense of the naked eye (the formation of a black hole, for instance). Like the artist’s own work, this is not true machine vision, but rather a poetically-extended prosthetic vision — the imagination of what an idealized machine might someday see. One might expect to experience a bit more of this confusion, of the extra terrestrial and the everyday, in Abbas’s apocalyptic nightclub—not to see it in a literal sense, maybe, but perhaps to understand it as a platonic ideal instead.