UCCA (798 Art District, No. 4 Jiuxianqiao Lu Chaoyang District, Beijing, China 100015) May 5 — August 18, 2013

As Clement Greenberg once remarked, an art critic is obliged to report their value judgements. It is a statement that seems obvious, yet isn’t, in fact. In an essay related to those published posthumously in “Homemade Esthetics” (sic). — a book in which he expressed great distaste with the state of art criticism — Greenberg stated that value judgements are the substance of aesthetic experience, a fact he refused to debate. He went on to assert that these judgements are “acts of intuition,” and that to define intuition of this kind one must resort to the word Taste. This kind of evaluation, he insisted, is essential “for the sake of what’s in art’s gift alone.”(1)

I invoke this essay because until now, I have disliked looking at Wang Xingwei’s paintings. Recently, however, and in the wake of seeing his work at UCCA (a very grand solo exhibition, and one work in the Duchamp show) and at 0100001 (supporting sketches), this may have changed. But before giving way smoothly to commending the work, it is tempting to pick a little at this “like” and “dislike.” For Greenberg, “…Art is first of all, and most of all, a question of liking and not liking — just so.”(2) As well as positive reactions, unfavorable judgements can also be useful, or engaging. Think of when an interviewee dislikes their questioner — quite often more enticing — or socially how much more energy is apt to criticise than praise something, or someone; we remember mistakes acutely, too. Negativity and development tend to etch themselves more deeply than what is easily positive — such is human nature, perhaps.

王兴伟,《无题(花盆老太太)》,布面油画,117 x 91.5 cm,2011

But what of this change from dislike to like? There is a particular relationship with things one used not to like. In art, the critic Peter Schjeldahl advised one reader to “stick around” in the presence of a work of art they hated, believing that judgement of art often evolves from initial dislike to appreciation, whereas as works liked at the outset can later prove disappointing (3). The artist Edward Ruscha apparently said “Bad art is ‘Wow! Huh?’ Good art is ‘Huh? Wow!’” The search for a frame for this alights on “acquired taste.” In more moderate circles, this is described simply as something one has “come round” to or grown to like. Elsewhere, philosophers like the late Peter Goldie believe certain tastes are acquired wilfully and self-consciously — faking it until the sensation becomes true (an argument he delivered in a lecture entitled “Oysters and Opera: How to Acquire an ‘Acquired Taste’” (4)).

Arguably, Wang Xingwei’s work is an acquired taste — at least of a “Huh? Ah…” kind (if not yet “Wow!”). The combination of this huge eponymous exhibit at UCCA and a show of his preparatory sketches at 0100001 in Caochangdi regardless convey an active mind and quick hand — the swoop of Wang’s pencil and brush over subjects as varied (or sporadic) as penguins, Duchamp, socialist realism, himself, Mao, suitcases, death, art history, football, Nazism and Summer boating. It is unusual to have the benefit of multiple shows at the same time, which certainly adds to one’s experience of the work.

王兴伟,《进化的步伐》(1-4),布面油画,130 x 440 cm,1997

But first of all, why might one dislike his output? Wang floats himself in a strange stream of imagery; it has been likened less to fine art than to a filmic method, where a particular figure or posture sometimes appears in successive frames, slightly altered. Here, for example, is the old lady in the window with flower pots and clumsy mitten-like hands apparently threading a needle (untitled “Bonsai Old Lady”, 2012); here she is again with flower pot for a head; on a balcony; in a room. It comes across almost like a rude sampling — “How about this?” the artist seems to say, “Or this?” It is a transgression that can feel crass or, perversely, lazy; it deflates the artist’s decision — that confident, respectful address to a chosen composition. This seems to be less the transformation of materials expected of good artists and more an indifferent probing — its results delivered like so many sample products (certainly an affront to the temple of art).

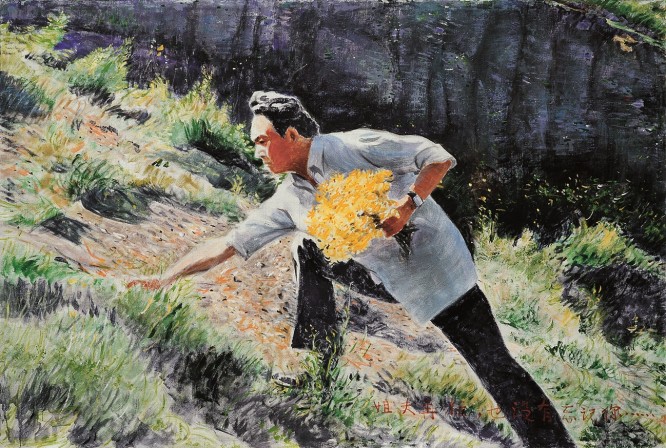

Other works are downright horrid, even if deliberately so. “Stupid” (1997) evokes the very worst of what “contemporary Chinese art” has offered to foreign buyers in the past. A painting like “Extortion” (2004) mimics naff village scenes of the kind found on cheap greetings cards from the South-West of England. Disconcerting is the way in which these apparently indifferent subjects sit with far more serious or sinister imagery, which might come in the form of self-portraits or murderous scenes like the body being butchered in “Doctor Bethune” (2010). Hitler appears, too, as one of so many characters in Wang’s flippant cast. The series “Developmental Step” (1997) with its embarrassment of monkeys and fireside Neanderthals is far removed from most things one could call artistically appealing. Then there are the rather irritating cartoonish paintings of a couple in a punt, or enacting a heart shape with their bodies as if in an advertisement, or gliding along on suitcases or scooters — scenes that are shallow and un-diverting. There is a sense of a scattergun approach, and with it an atmosphere of stiffness and haste.

王兴伟,《无题(卖鸡蛋)》,布面油画,240 x 200 cm,2007

Some find Wang’s work uneven, and indeed, there is marked inconsistency in his application of paint and his “style” (which is not one, but many); where “Ascending” (1999) is subtle and smooth, for instance, the untitled (“Penguin Trolleys,” 2008) is patchy to the point of looking pixelated. The painting of female figures on an inflatable dingy (untitled “Hostess and Nurse in a Raft”, 2005) emulates the visages of Tamara de Lempicka, and Wang has done a Chinese soldier in the pose of Manet’s 1863 “Olympia” (“Recruit,” 1998). But why? The appeal of the works or their artistic consistency is not sufficient to justify a retort of “Why not?” In general, the collective aura of the works is ambivalent — a combination of fervour and indifference, unstable yet earnest. Is this a part of “art’s gift,” as Greenberg had it? Wang Xingwei himself declines to discuss his work critically (though the UCCA catalogue has a daunting stab at this with three dense essays). He is self-effacing, in claiming that his work is not so grand a thing as “art,” and by describing paintings that have “a certain stupidity to them.”(5)

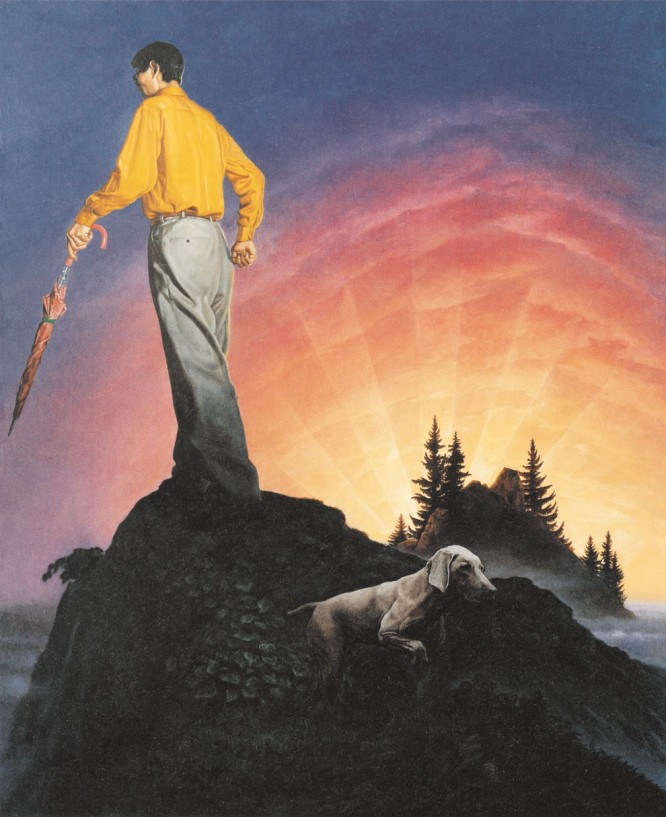

And now to the other view — the intangible thing which slows one’s pace through the UCCA show, dispeling the dislike and turning it gradually to attentiveness, regard. True, there is a disarming and fluctuating range of paintings here. Yet in some way, this shameless mass becomes a measure of the works one finds really “good” — almost as if this was the artist’s own aim. Take, for example, the “Developmental Step” series with its ugly brown colour and similar content and, nearby, “Midas” (1997), a smooth oil painting containing the figure of Duchamp, posed like the Thinker and with a hand on the head of a gold statue of a child, gazing at and past his bottle rack in a dark room. A work such as this clearly marks the intrigue and subtlety evident in Wang’s work of the 1990s — before the penguins and air hostesses really appeared. Further works supporting this include the mid-1990s series with a man wearing an ochre shirt that line one wall at UCCA. Called “My Beautiful Life” (1993-5 — the man with his arm around a woman as they lean over an urban canal bridge at sunset), and “Dawn” (1994 — again, a couple, the man this time gesturing into a cobalt distance). These are enigmatic images, and beautifully executed, invoking veiled personal story and common experience. Two further works — “The Oriental Way: the Road to Anyuan” (1995) and “Blind” (the following year) make powerful reference to Maoist imagery — the great leader atop great landscapes, on an equal footing with a dramatic sky. The skill with which these have been done is undeniable; the compositional language through which they speak retains the compulsion of a propagandist purpose.

王兴伟,《盲》,布面油画,220 x 180 cm,1996

Wang Xingwei’s talent as a painter draws one in elsewhere, too. Much as he might seem indifferent to his subject-matter (he is quoted in the press text as calling an artist “a postman…who should not be curious about what is inside the envelopes”), his brushwork certainly is not. He is an artist of consummate ability with his chosen medium, and there is delight for the viewer (and the artist, too, one suspects) in the sheer surfaces of the paintings — the creases in clothes or the portrayal of light; foliage, skin and texture can and do leap from his brush. Furthermore, Wang’s talent in reinstating compositions recognisable from art historical masterpieces — Manet’s aforementioned “Olympia” as it reoccurs in the self-portrait “Ascending” (1999) can be unduly striking, with a seductive omniscience.

Indeed, if one were seeking an artistic figure to interrupt a canonical respect for art history, and dispute the assumption of a pure-style-per-artist, then Wang is rightly famous for doing so. As such, his oeuvre as conveyed through this UCCA retrospective comes across as artful and perhaps intelligently sardonic (read teasing), yet still affirming the inherent singularity of an artistic mind and its application. In a recent profile of the artist which is worth quoting at length, Zhang Li approaches this idea:

“The significance of Wang Xingwei’s painting lies not in his paintings per se, but in their treatment of the great construction that is painting. His paintings do not express anything by themselves. Rather, their effect…is relational. They relate to a system constituted by all paintings, ancient and modern, foreign and Chinese.”(6)

王兴伟,《青年公园的星期天下午》,布面油画,165 x 300 cm,2009

But here one might stop this acquired taste in its tracks — that is, if the taste acquired is meant to relate to Greenberg’s description of intuition and the sheer “liking” of an artwork. At this point, one is inclined to examine this acquiescence, begging the question of what an acquired taste is in the context of the art world — largely thanks to its market, a hotbed of coercion. Do directors of art institutions, for example, choose to show work they like, or find “interesting,” or which to educate the public about, or that their imagined audience will like? UCCA’s text certainly leaves little room for disagreement, calling Wang a “hero of the avant-garde” and a “key figure,” the complexity of whose vision “proves the depth and richness of the tradition to which he belongs;” such wording is likely to forestall intuition. That said, those already fond of the work and sure of an intuitive liking of it are more likely to stride past the clamouring wall text; would there be fewer new admirers of Wang’s painting if it wasn’t there? Such issues are endemic to current conventions of display.

王兴伟,《姐夫再忙,也没忘记你……》,布面油画,200 x 300 cm,2001

In his chagrin, Greenberg complained of art works being constantly “explained, analyzed, interpreted, historically situated,” but of the “responses that bring art into experience as art, and not something else” as going unmentioned. Surely, to call Wang Xingwei’s work strong on the basis of its relational pull falls into this trap. Thus intrudes the idea of art that is “interesting” — that word so un-useful to intuition and bound to the intellectual line. To call paintings “relational” makes them sound like verbs, without whose object (other paintings/art history), their ability is gone. And is the idea of the artist’s “cleverness” with the materials he finds to be a segue from disliking to liking his work? What of Wang’s paintings apparently being effective as a group, collective, but not individual? Perhaps, in the current context, they become an acquired taste mainly on the basis of the correspondences and canninessamongst them and in the midst of art history — an idea that seems to separate an acquired from an intuitive taste for something, or some-art. If a taste for Wang Xingwei’s work is an acquired one, but how has it been acquired — along which tracks? What does one ask of art, and what is driving what people “like” now in terms of the Chinese art scene?

In 2010, Peter Schjeldahl opened a lecture by asking “Can we talk sensibly about what we like about art?” What is suggested or agued here relative to Wang Xingwei’s work is not necessarily acceptable; perhaps these questions are being taken too far (or not far enough), and exposed for their impossibility — or circularity. There’s the rub.

(1) Clement Greenberg, untitled essay in Partisan Review, Volume XLVII Number 1 (1981).

(2) Idem.

(3) Various readers, “Questions for Peter Schjeldahl”, New Yorker, February 16, 2009.

(4) Peter Goldie “Oysters and Opera: How to Acquire an ‘Acquired Taste’”(lecture, the University of Auckland, New Zealand, September 21, 2010).

(5) LEAP magazine interview with Wang Xingwei (no date), accessed June 19, 2013. http://vimeo.com/26714891.

(6) Zhang Li, “Wang Xingwei: True or False”, LEAP, August 8, 2011, 129.