The world’s best art selling machine continues to be the Art Basel trade fair. Over 300 galleries from around the world, 2,500 artists and 65,000 visitors, including 70 museums. Throngs of collectors piled into its crowded halls, the Eurozone crisis apparently encouraging investors to buy (blue-chip) art. Continuing financial uncertainty, though, also meant galleries tended to show more conservative (blue-chip) work.

Established in 1970 by three gallerists Ernst Beyeler, Trudl Bruckner and Balz Hilt, it has grown and grown, particularly with globalization in the 1990s when it was led by Lorenzo Rudolf, now the director of Art Stage Singapore. Rudolf and his successor Sam Keller took the fair to Miami Beach and now of course ArtBasel is also the owner of the Hong Kong art fair, ArtHK. In the Basler Zeitung, however, Christoph Heim commented that while the new directors, Annette Schönholzer and Marc Spiegler, are perfectly competent trade fair technocrats, ArtBasel is beginning to lose its passion. Something is missing — we’re out in the sun but we’ve forgotten the parasol.

This feeling of hubris arises partly due to the fact ArtBasel this year opened shortly after Documenta, always a very strong survey exhibition — and this time quite extraordinary. In its wake, something so commercial as an art fair will inevitably feel thin. What makes Basel special is not just its scale. Certainly it has a high-quality curatorial program, including Art Unlimited (large scale projects), Art Statements (emerging artists), Art Features (gallery curated shows), films, conversations and talks. But much of its aura is to do with Basel itself. Home to only 160,000 people, Basel has a long history of supporting and appreciating art. It has numerous world class museums, which always put on outstanding exhibitions during the fair: this year included surveys of Jeff Koons at Fondation Beyeler, Tatlin at Museum Tinguely, Renoir at Kunstmuseum Basel, and Hilary Lloyd at Museum für Gegenwartskunst. The Schaulager even built a temporary pavilion in front of the fair because it is currently undergoing renovations. And when Basel is sunny, like it was this year, this medieval city on the banks of the Rhine is very pretty. You can promenade in the museums, sprawl in a cafe, doze in a park or gently float away down the river, but you have to avoid the giant barges that use the river too.

ArtBasel remains for now the exclusive pinnacle of the commercial art world, but at least a fifth of exhibiting galleries could be replaced without affecting quality; indeed, it could be even better. Exclusivity can breed complacency, while cautiousness becomes stultifying. As Frieze has shown, new art fairs can be wildly successful. And as the first art fair, Cologne, demonstrates, they can also decline.

Art Unlimited

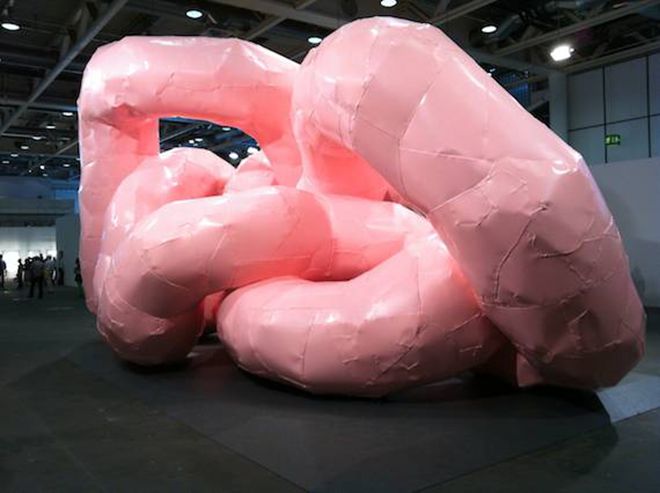

ArtBasel keeps the crowds entertained with numerous side programs: Art Statements for younger artists (this year a little dull), Art Unlimited ostensibly for large format projects (but not necessarily), Art Parcours (an art hunt designed to make you discover a new bit of Basel each year), Film, Salon and Conversations for talks and conversations. The best of these this year, as so often, was Art Unlimited, this year curated by Gianni Jetzer, the director of the Swiss Institute in New York.

One of the most important gallerists to have emerged in the international scene over the past decade is Johann Koenig from Berlin. Once again his artists, whimsical and rigorous risk-takers, were prominent. These included Alicja Kwade and (above) Michael Sailstorfer, whose “If I Should Die in a Car Crash, It Was Meant to Be a Sculpture” (2011), referencing Roland Barthe’s “Death of the Author,” German history (it’s a non-functioning kit Porsche car), and Hollywood myth, and Carl Andre minimalism, was one of the show-stealers.

ArtBasel, Liste & China

by Chris Moore