PACE Beijing (798 Art District, Beijing), Sep 28–Nov 19, 2016

Sol Lewitt’s representative essays, “Sentences on Conceptual Art” and “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” were first published in Artforum in the late 1960s, but it was not until The White Cover Book was published in 1995 that they and Joseph Kosuth’s “Art after Philosophy” appeared in translation in Mainland China. Lewitt’s essays originated in his individual creative experiences and engaged in a somewhat partial summary of the wave of Western conceptual art around the 1960s. Within the texts, Lewitt steadily lays out the confrontational stance of the new art form, repeatedly authenticating “conceptual art” and its corresponding creative practices through dualistic premises. What he names conceptuality is rooted in both intuition and the spirit of rationality. By avoiding subjective judgments, one sustains an ongoing exploration of the inevitability of ideas (linian biranxing). Proposals and designs serve as creative methods for revealing minimalist, non-aesthetic, and formal limitations. The other art form that he offers in contrast is one that is grounded in observation and perception, with an emphasis on aesthetics and subjectivity—one that occurs after the fact and seeks not to avoid the random or aleatory, the sum total of the visual and perceptual arts that attach importance to the materiality and emotive power of form.

Perhaps we can glimpse, in the texts by Lewitt and Kosuth, the conditions and foundations that gave rise to Conceptualism in the West: a weariness of sensorial aesthetics, a reassessment of the properties of an artwork, the affirmation and legacy of Duchamp, and the attempt to organize a new mechanism of artistic expression and judgment. It is possible that the comments of Lewitt, Kosuth, and others had an effect on the torrents of China’s post-modernist wave, for they certainly aligned with the concurrent changes moving through Chinese society and the indications of self-transformation among Chinese artists.

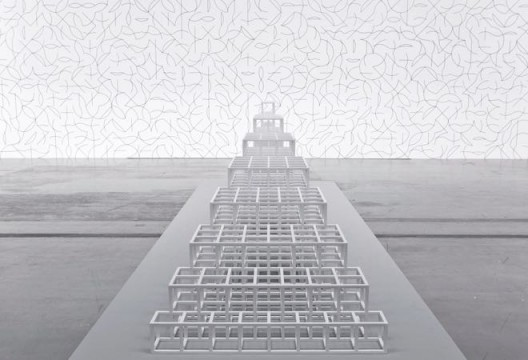

During the mid-1990s, Zhang Xiaogang entered an era of peak productivity. In a series of works that raised doubts about art from an external perspective, he nevertheless continued a stubborn exploration of the interior of art and of a personal spiritual realm. Now, more than twenty years later, these two distinct personal systems, which arose from their own respective environments, coexist in an exhibition at Pace Beijing, presenting two bodies of work that look starkly different. LeWitt’s pieces include seven groups of work made during the 1990s. Adhering to the ideas in his texts, these works are primarily implemented design proposals. Zhang Xiaogang’s recent paintings continue his explorations of emotions and sentiments completed in a stream-of-consciousness style. Searching through memories for nostalgic scenes that “stick”, he pieces together with threads and fragments spectres of lonesome age which wander the damp, narrow corridors of dreams.

If we examine the roots that engendered this oppositional question, we find no judgments regarding who was right or wrong. The establishment of any standpoint depends greatly on artists’ individual choices and ability to implement them, and the fluctuations of theoretical trends in different regions, as well as the traction gained in the art market are an entirely different matter. It is ironic that the receptivity of the art market or exhibition system to different ideas often far outstrips the receptivity of individual artists. Because concepts exist through their expression, compromise is a form of self-destruction. As for the artists themselves, the process of affirming oneself is rife with indecision, pain, and despair. Attempting to break out, one confronts an internal process often accompanied by the deepest questioning, fragmentation, and denial of the self. The artist must also constantly remain vigilant towards the mechanisms of self-preservation and outside voices of criticism or praise. It is here that the two artists take different paths to the same destination: Lewitt, braving the risks posed by a thorough denial of art’s status, used decisive wording and formal restraints to establish his concepts. Meanwhile, from the bloodied flesh of the spirit, Zhang Xiaogang extracted and preserved, one slice at a time, the memories on the tips of nerves. What cannot be denied is that such reflections on the ontology of art as well as on what is within and without art will continue to be debated.

展览现场

展览现场

展览现场

展览现场

展览现场

展览现场

展览现场

张晓刚,《黑沙发》,布面油画,120 cm x 150 cm,2016

张晓刚,《理想者》,布面油画,46.5 cm x 61 cm,2015