Shi Jinsong (b. 1969 in Dongyang, Hubei Province) is one of China’s most adaptive artists yet, despite—or perhaps because of—renown for his shiny, dangerous “Nezha” children’s wares (e.g. a baby stroller or pacifier) composed of martial arts weaponry, he remains little understood and seemingly overlooked. A joint show with his wife, Xiang Yun, at Galerie du Monde in Hong Kong affords an opportunity to reexamine his work, with particular emphasis on his tree installations.

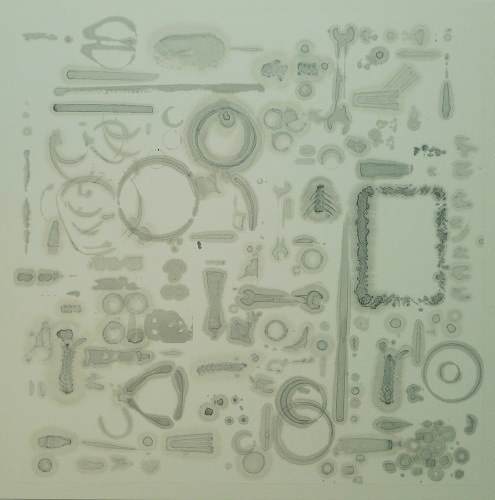

The forerunners to his “Nezha” line of baby products launched in 2005–2006 (“Nezha” refers to a folklore trickster and dandy, in modern China often adopted as the god of gambling) included perverted famous corporate logos (“Secret Book of Cool Weapons,” 2002) and office equipment (“Office Equipment-Prototype No. 1”—a computer workstation whose computer controls are torture implements). For the 2006 Shanghai Biennale he produced a new “product line,” “Halong Kellong” (translated: “Hello-Clone”), fusions of old-fashioned Chinese peasant tractors and American Harley Davidson motorbikes “pimped” with shining traditional Chinese weaponry and a “dragon” aesthetic—no cheap knock-offs these, however contradictory the presence of the tractor as transformed Communist agrarian symbol of peasant production and modernization.

While all these works are sadomasochisticly fun and seductively sinister, analysis has tended to be out-dazzled by the sheer “bling” attractiveness of the “consumer” items. Clearly they are about the perverse and perverting desire of consumerism, especially in China, but Shi Jinsong’s work is also closely tied to a traditional Chinese aesthetic and philosophy—these words are easy to write but so often used as to be almost meaningless. Shi Jinsong engages in the invention of mythologies of things as ideals, much as the true shanshui painters would create ideal landscapes with mountains, trees and rivers. Which is to say that invention and transformation are not corruptions of an ideal but rather its embodiment.

史金淞,《摇摇马》,不锈钢,66 x 86.5 x 39 cm,2008。图片:前波画廊

For “Alors, la Chine?” at the Centre Pompidou in 2003 he created “A Life of Sugar,” an installation made of caramel and designed to melt over the course of the exhibition, and also the floor. The “Halong Kellong” display at the Shanghai Biennale was accompanied by renovated and repurposed shipping containers that included dining facilities and a cinema and also a meaty muscle-suit—no doubt parodying in part Zhang Huan’s performance “My New York” (2002). Then in 2008, Platform China in Beijing held the exhibition “Fire His Breath, Jade His Bones: New Work by Shi Jinsong,” which included one of the most striking depictions of hell ever devised: a giant onanistic motor whose monomaniac purpose is to drive itself, with the result being that it became so hot it glows a molten red, threatening its continued existence and even that of the gallery displaying it. The installation is so large and heavy that it remains to this day, at slumber in the gallery. This is Skynet made of the grinder in Duchamp’s “Large Glass.”

At this time, Shi Jinsong had already begun experimenting with drying dead trees. “Gentle Breeze and Waning Moon” (2005-2007), composed of “Various types of tree roots, trunks, branches, willow, glass, and steel,” perfectly exemplifies the way Shi Jing transforms reality (a tree that lived) into an idealized con-fiction (a sculpture of a tree made out of a tree). Shi is not the only prominent Chinese artists to work with living and dead trees. Shen Shaomin began his “bonsai” series of tortured trees in 2007. More recently Ai Weiwei has presented his own Frankenstein-monster entitled “Tree” (2011), exhibited with “Rock” (2011), porcelain “stones” made in Jingdezhen. This year Cai Guo-Qiang’s created “Eucalyptus” (2013), a complete 31-meter long dead eucalyptus tree set on its side, currently on display in the QAGOMA museum in Brisbane. Both Ai’s’s and Cai’s works are deliberately grand, theatrical statements, whereas those of Shen and Shi are more poetic philosophical pieces, but while Shen concentrates on the aspect of torture, correction and subjugation of a living thing, Shi’s trees are delicate, ghost-figures, the remains of the day.

Sometimes Shi Jinsong burns the trees, reducing them to charcoal sticks. Sometime he inserts animal teeth into the delicate branches, such as in “Pavilion Garden” (2012) (the word for tooth in Chinese—yá [牙]—puns with the word for bud [芽] raising simultaneously notions of rebirth and consumption). Always they are faithful attempts to reconstruct what has been broken, to restore the dead to life. It is an impossible, task and in the failure of these Sisyphean efforts lies the art and remonstration with our ethics.

史金淞,《杨柳岸晓风残月》,各种树根、树干、树枝、柳条、玻璃、钢材,600 x 230 x 300 cm,2005-2007。图片:前波画廊

An alternative version of Shi Jinsong’s reconstructions is found in his scholar-stones carved from old walls, often from buildings that have been demolished. Scholar-stones are traditionally used in gardens to create a point of focus for contemplation. While the traditional garden stones occur naturally in nature, their epicurean selection and delectation has become in many ways an artifice, mere garden decoration, even a perverted obsession that far from bringing contemplation, interrupts it (think of Zhan Wang’s mirror-polished stainless-steel versions). Shi Jinsong returns the stones to their original function by inventing new versions of them that remark their origins and original purposes, quietly critiquing their new one even.

In recent years Shi has experimented with installations of “Chinese landscapes,” with ink pounded from the ash of incinerated animal skeletons and trees, swept through a room in calligraphic-like gestures, such as “Over There” (2011), whereby actual space becomes the imagined landscape, or ink paints over living space—the space of our environments and the environments we have changed, damaged and destroyed.

Shi’s scholar stones, heavy and awkward, recycle demolished walls and his trees, delicate and fragile, recycle dead branches. But their implied urban environmentalism, their anthropology, is as much concerned with our psychological environmentalism, the state of our heads—what has been going on in them, what damage we have done them. The purpose, then, of these sculptures is to return the act of looking at sculpture to its original purpose, the contemplation of the self in the world, and how we measure up in it.

Current exhibition:

Shi Jinsong and Xiang Yun “You Won’t Believe it”

Galerie du Monde (108 Ruttonjee Centre, 11 Duddell Street, Central, Hong Kong) Mar 12–May 8, 2014

史金淞,《东西集之三》,纸本水墨,75.5 X 143.5 cm, 2014。图片:世界画廊

史金淞,《雙松園》,樹木殘骸和建築殘骸, 尺寸可變,2012

史金淞,《那边》,装置,碳化一棵树和若干动物的骨骼,2011