Two years ago, news that the collaborative project DIS was to curate the upcoming Berlin Biennale provoked ripples of excitement in the German art capital. No one knew much about this New York-based group. Monopol, the Berlin art magazine which prides itself on being youthful and well-informed, rather timidly asked: “No one is sure how best to describe you. Are you artists, journalists, or a photography agency?”

The answer by Marco Roso, a member of DIS, didn’t help much to clarify matters. “We run an art magazine and a photography agency, but we aren’t journalists. We come from an arts background. The magazine is a platform for our artistic practice, for our friends, and for people who interest us.”

Soon after the website first launched, it was apparent that DIS was able to fulfill their promise of delivering something completely new that would affect many people. Very rapidly, it advanced to become one of the most visited digital spaces in the international art and fashion scenes. They published strange Soundcloud mixes, fashion shoots in galleries of interns clad in Normcore outfits (a term actually coined by the K-Hole group in New York), long essays on the subject of the Anthropocene, and 3D-printed accessories—documentation of the digital everyday simultaneously satirized and celebrated.

DIS’s explicit rejection of the framework and signification of the retromania still apparent in US and European fashion design continues to disturb much of their audience today. Instead, a travesty of consumer culture dominates their content, expressing both unease with and attraction to the minimalist user interfaces of brands such as Apple and Google.

Key, for instance, is a video which appropriates the aesthetic of an advertising clip: a red pump slides into a trekking sandal to the accompaniment of a looped soundtrack (part of the Shoes in Shoes series); or the photography series Shoulder Dysmorphia(2010), in which the characteristic silhouettes of various fashion designers are transferred from the structure of the clothing to the bodies of their wearers; this is entitled “Get the Lanvin Look for Live”. A perverted fantasy of future plastic surgery demonstrates the modus operandi of contemporary fashion labels: it is in the body, the images say, no longer on or next to it; the outside is already inside us.

Made up of Lauren Boyle, Solomon Chase, Marco Roso and David Toro, the New York-based collective follows a Modernist, century-old principle with almost all of its interventions: the desire to forge connections between worlds. Visiting their stark white New York office, one saw technophiles swiping around on their smartphones, circling from one subject to the next: fashion, sex, sociology, technology, popular culture, politics, recounted via one of the most far-reaching and democratic mediums in the history of publicity: the internet.

From 2010 to 2012, certain visual codes or memes whose meaning was not immediately apparent because they exuded this overdetermined, porous tech-brand aesthetic, were known as “post-internet” and centered around “DIS”. Today, these terms have fallen out of fashion and are no longer in use. In the art world, however, they continue to be used as ciphers out of which a new, powerful art movement emerged: Post Internet. The term serves to describe a generation for which the internet no longer exists as an outside, but as a medium in one which is permanently submerged—liked fish in water, a natural habitat. DIS, early on, featured artists ascribed to the post internet movement such as Ryan Trecartin, Hito Steyerl, Jon Rafman, Aids 3-D, Simon Denny, Petra Cortright or Yngve Holen.

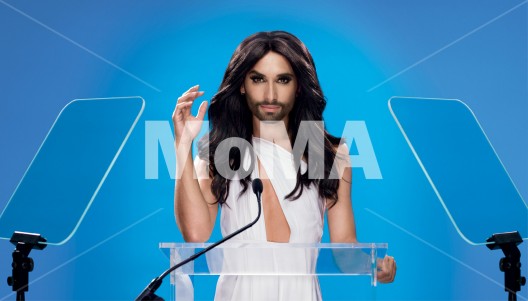

Since then, DIS themselves have participated in art exhibitions from site-specific museum and gallery exhibitions such as “CO-WORKERS CO-WORKERS—Network as Artist” (2015, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris) to “Ocean of Images: New Photography 2015″ (The Museum of Modern Art, New York), “DIS Image Studio” (2013, The Suzanne Geiss Company, New York) or as part of “EXPO 1: New York” (2013, MoMA PS1, New York).

Almost simultaneously, a new tendency in philosophy in the form of a reconceived materialism came to the fore: Accelerationism. This school of thought postulates that received forms of leftist critique are no longer functional, and that capitalism can only be overcome via its own acceleration and eventual overheating. The critique is thus quite similar for both post-internet artists and accelerationists. As the critic Morgan Quaintance wrote in Art Monthly: “Post-Internet art is almost totally apolitical and uncritical” and “post internet art stands for the depoliticization of its precursors due to its capitulation to the culture industry and its desire for the corporate.”

In their work, DIS refers to other artist groupings from the nineties both directly and indirectly. These include Bernadette Corporation, who invented the concept of the artist collective as a corporate entity, or Art Club 2000, who experimented with affirmative adaptations of mainstream consumer culture. Leafing through Alexandra Mir’s 2003 book Corporate Mentality today and observing her use of commercial imagery and corporate culture in the art world, there is a recognizable feedback loop.

DIS, however, deviates from its antecedents: they didn’t originate within the art world and thus never fully belonged to its system. Rather than appropriating the practices of other artists, DIS work with the aesthetics of consumerism. In 2013, they founded DISimages, a stock photography agency where artists could submit images under commercial license. DISown, an online shop selling objects that walk a line between artwork and product, with the aim of expanding economic opportunities for creatives was also founded around the same time. It seems the shop hasn’t had much commercial success, however.

Symbolically, DIS remain flexible—but it remains to be seen whether this increases their potential to disrupt the art system. It also is unclear whether the name DIS was a programmatic choice from the beginning on. The artist Hito Steyerl recently noted in a round-table discussion organized by Spike Art Quarterly that “When the financial crisis began, and many things occurred, including a nearly global civil war that we are now experiencing, the contemporary was liberated once more and a wholly different aesthetic emerged. While it wasn’t new, certainly, in the art world it seemed new.”

The New York-based collective has repeatedly cited this crisis in interviews as a key moment that revealed the true face of creative capitalism which, after the crash of the property market and the global financial market, was rendered in an entirely new context. Reading DIS’s intentions for the Berlin Biennale, this resonates: “The 9th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art will seek to materialize the paradoxes that increasingly make up the world in 2016: the virtual as the real, nations as brands, people as data, culture as capital, wellness as politics, happiness as GDP, and so on.”

The text is simultaneously a form of political positioning and also as smooth and almost banal as the surface of an iPad. Many members of the art world remain suspicious of a formation which does not differentiate between art and Instagram, art and the culture industry, the artwork and a product. This suspicion is valid. The practices of DIS, Hito Steyerl and Ryan Trecartin are united by the fact that they want to break with art history and instead enter into an open and inconsistent relationship with the world, a world whose capitalist system expresses itself in company structures, corporate design, advertising and international politics, and is completely saturated with it. Representing and thereby perhaps grasping this seems to be their interest. A classic medium such as painting has very little to do with it; on the website of the Berlin Biennale (which itself looks surprisingly similar to the Deutsche Bank website), it says: “120 artists will participate, but there will be only one painting.” The medium, then, is not a space which can represent the contradictions of the modern world.

The “white cube” absorbs everything and renders it serviceable, and hence harmless. Art, in capitalism, is a valuable good. The project DIS, which is often accused of not occupying a position, of being harmless and ungraspable, has the potential to utterly destroy art by rendering everything as art. Finally, their project entails an almost incredible hope of not belonging to the broken, closed art system, and therefore to merely contribute to it from a position of freedom.

In comparison, classic Adornian critique appears tired and no longer useful, and the self-flagellating discourse of the art system something that merely rotates around itself. Concepts of critical distance, opposition and dialectic opposites may simply be reinventing themselves. History is something that lies ever more close at hand, like an organically constituted thread reaching into the now. The fluid network is permanent.