by Chris Moore 墨虎恺 2018.06.07

translated by Lin Bai Li 林白丽

Shi Yong (b.1963, Shanghai) is a mercurial multi-media artist, shifting from performance art to installation to video to sculpture in strikingly different styles always maintaining an acerbic, analytical edge, often focusing on cultural and economic systems, including the art world.

Among his friends, the influential Shanghai band of artists that includes Zhou Tiehai, Zhang Enli and Xu Zhen, Shi Yong is renowned for his critical eye and lugubrious humor. In exhibitions, he is a peerless guide but too frequently self-effacing about his own substantial artistic talents. In recent years, Shi Yong took a break from being an artist, instead working for ShanghART, travelling around the world for the gallery, assisting with art fairs; which is where Shi Yong and I would often meet, occasions absurdly Apollinair-ian as we each struggled with our linguistic limits. As well, as an artist, Shi Yong is also an art collector, supporting numerous young artists when they were just starting. He doesn’t talk about it, that’s not his style, but young artists do.

Chris Moore (CM): Where did you grow up? What was family and school life like?

Shi Yong (SY): I was born in Shanghai, and I studied, work, and live here. My family had no connection to art. However, my parents were never opposed to me studying art. I remember when I started to take an interest in drawing, my mum bought me color crayons and drawing paper. You have to remember that during that period (after 1968), our living conditions were still relatively poor. So it was quite a luxury to own a box of color crayons. I studied Chinese painting in primary school, but I didn’t like it, because I found it particularly dogmatic. Upon entering middle school, I joined the school’s art group and started learning drawing and color theory. After graduating high school, I was admitted to Shanghai Light Industry College majoring in art and design. But the truth is, what design was there to learn in China in the early 80s? It was no more than an excuse to have ample time to paint. It is a pity that I did not get to keep any of my works from that period. None at all, such a shame.

CM: So how did you become an artist?

SY: I’ve liked it since I was a child. So naturally I became tangled up in art. It is hard to imagine what else I would do if I were to quit art. In my student days, I always dreamed of becoming a great painter. But by the early 90s, I thought of nothing but how to break away from drawing, because my drawing tendencies, often obstructed my thinking. So after 1992, I stopped drawing all together, allowing myself to search for possibilities of art outside of drawing. It is then that I decided to become a contemporary artist.

CM: It seems there is a group of Shanghai artists, many of whom became part of ShanghART early on, and most of whom are still part of ShanghART. Do you think of yourselves as a group or just a bunch of friends?

SY: First all all, we are all good friends, many of whom had already met in the 90s. In 1996, with the founding of ShanghART, I found that many artists I knew were collaborating with the gallery. I too started working with ShanghART in 1998. I feel that ShangArt then was the equivalent of a contemporary art center. If there was an exhibition or an event at ShanghART, we would all go there for the opening. We often joked that we were all part of the same “work unit”. In that light, we were indeed like a collective, even though our works were very different from one another.

CM: How did you meet each other? (Zhou Tiehai, Yang Fudong, Xu Zhen, Zhang Enli, Ding Yi, Lorenz, etc.)

SY: After 1989, there were not many artists working in contemporary art (what was then called avant-garde art or experimental art) in Shanghai, or even China. So after hanging out at a few get-togethers, or seeing each other at art events, we naturally came to recognize one another. Ding Yi was the first artist I met through Song Haidong. I remember that he rented his studio from a farmer in Hongqiao. It was surrounded by high-rises, which made his studio seem like an urban village.

CM: And how did you meet Lorenz?

SY: I don’t even remember. I just know that one day in 1995, he came to the school I was working at to see Shen Fan (a ShanghART artist). We happened to meet in the office, and we politely greeted each other. I didn’t know if this counts as an official introduction. Anyway, I went to his place on Jianguo Road. It was the first solo show, an exhibition of Zhou Tiehai’s collage work.

Shanghai

CM: How is the Shanghai art scene different from, say, Beijing? Is the humor between Beijing and Shanghai artists different? How so?

SY: Since I was born in Shanghai, and I never truly left, I’ve completely become one with the city, from aspects of language to my daily routines. So it’s hard to accurately describe it all at once, kind of like “when you are in the fog, you don’t know you are in the fog”. Only when you are trying to compare it with other cities, you will realize the differences between them! In the past, we often used a vivid metaphor to describe the differences between Beijing and Shanghai in terms of their artistic temperaments “生猛海鲜” “raw and fierce seafood” (trans note. This term came from Cantonese and Macanese seafood restaurants and was used to mean seafood so fresh it is jumping out of the pot). As the political center of China, Beijing has a direct and forceful resistance to ideology, so in terms of artistic temperament, Beijing is very “raw and fierce”. As the economic center of China, Shanghai isn’t so direct in confronting reality as Beijing, preferring instead to use individualized perspectives to explore our current reality. So in terms of artistic temperament, Shanghai is more intellectual, using gentleness to overcome strength, and is therefore more mild like “seafood”. As birds of a feather flock together, those who are “raw and fierce” flock to Beijing, while those who prefer [the subtle taste of] “seafood” would come to Shanghai. Of course, this kind of duality is nowhere as prominent as before, yet the differences still exist. Regarding humor, I think that the sense of humor in Beijing’s art can be felt instantaneously — it is intense and critical. In comparison, the humor of Shanghai’s art is colder, marked with an irony that imparts a certain wisdom. These differences are determined by the different modes of thinking shaped by different environments and dialects.

CM: And how would you compare the art scene now to when you were starting out? How has it changed?

SY: In the early 90s after Tiananmen, Chinese experimental art entered into a period of stagnation. Artists practicing contemporary art were still relegated to the periphery, and the number of contemporary artists could not remotely compare with how it is now. Almost no spaces were willing to do exhibitions for us, let alone museums. For the mainstream art circle, contemporary art was nothing more than trash. When those who were previously repressed once again assumed positions of authority in the official art circle, they turned up their noses at contemporary art, having forgotten that earlier, they had been vilified in the same way. There were neither funds nor spaces. If we needed any space for events or activities, we had to make it happen ourselves, and that, of course, includes obtaining the all the funds necessary for the events to take place. If artists from other provinces came to Shanghai for art openings, or if Shanghai artists needed to travel to other places, everyone had to take the shabbiest trains and live in artists’ homes. At that time, not only did we get used to coping with an impoverished lifestyle, we also learned to take advantage of any kind of non-art spaces, even the city itself, using a quick and dirty but effective way to insert art into those spaces. It is these conditions, unique to China, which helped extrude the unique forms of art, typical of that era.

90

SY: Compared to the difficult state of affairs in the Chinese art world then, today’s art climate can be described as luxurious. In the mid-90s, the Chinese economy made astonishing leaps, which, coupled with a Chinese art market under globalization, became the motivating force to completely change the art scene. Those particular modes of art-making born under earlier historical realities soon dissipated — it wasn’t possible for them to continue to exist.

CM: And how has Shi Yong changed? Are you now part of the Art System too?

SY: As an individual living in a society, it is impossible not to change, whether you actively face reality, or passively accept it. That is why I did “The New Image of Shanghai Today” series. When you intervene in reality from the standpoint of an artist through the medium of art, you are already a part of the art system. You cannot change that.

Adding One Concept on Top of Another

CM: What was the appeal of performance art to you? How did works like “Words about Deportment ABC” (1997) and “Adding One Concept on Top of Another” (1998) develop?

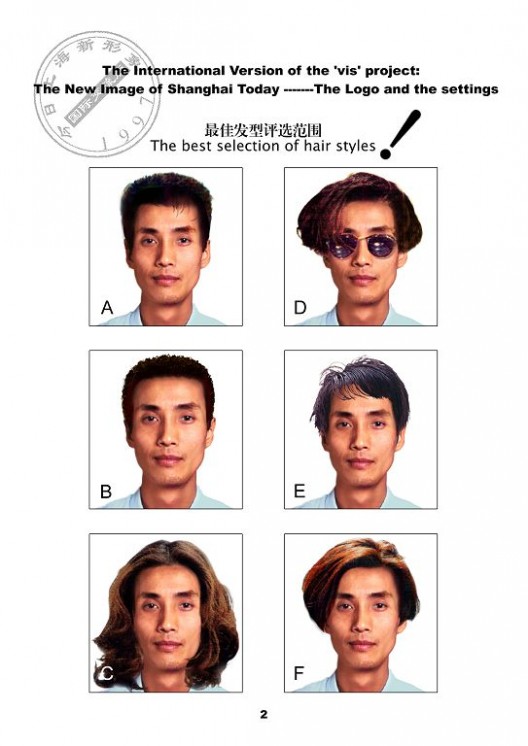

SY: It is convenient to use the body for performance art, or use the camera to record bodily acts, because for one it doesn’t cost anything, also it can be flexibly integrated into all kinds of places and scenarios. However, during the mid to late 90s, I was more interested in art performances that had a performative nature. Works in a later series almost all had something to do with bodily “performance”. Both “Words about Deportment ABC” (1997), and “Adding One Concept on Top of Another” (1998) were produced under such a backdrop. They emerged from an online project entitled “New Image of Shanghai Today, Please Choose the Best” shown in “Cities on the Move”, which was curated by Hou Hanru and Hans Ulrich Obrist in 1997. Using my face and body to model different hairstyles and clothing, I invited Western audiences to select which image corresponds to their perceived image of Shanghai on the internet. It was a conscious decision to give Western audiences the power to decide. As a window to the outside world, Shanghai was ambitiously entrusted with all the dreams of China. In “Words about Deportment ABC”, I devised a “perfection” exercise that was intentionally based on chapters from two books on self-marketing — “166 Strategies for Self-Promotion and Success” and “Business and Entertainment Etiquette Guide” — and exhibited it through photographic documentation and video production. I was less interested in the precision of imitation than I was in imitating communication techniques such as “public relations,” conveying the absurdity of supposed appropriate public relations. In “Adding One Concept on Top of Another”, I borrowed Joseph Kosuth’s “One and Three Chairs”, adding to it the image of a contemporary Chinese artist. As such, the chair’s original self-referential concept was transformed into the intertextuality between the chair and the sitter. The work reveals a reality of communication that nevertheless exists under the shelter of pluralism and cultural diversity strategies: how do we provide an effective stage and build a valid contemporary cultural background when both the center and periphery wish to be assured and protected?

CM: Why did you clone Andy Warhol? (In “Forever Gallery Scenery”, a 2002 photography work, and “Continuous”, a video from 2004 and 2005)”

SY: This is the first time I’ve heard that “New Image” has something to do with Andy Warhol. Maybe is is because of the similarities in appearance? In fact, this new image has nothing to do with Andy Warhol. Just like what I described in response to the last question, this yellow-haired, cashmere wearing, new image of Shanghai with cool shades was actually selected by Western audiences. That is to say, I am not the real designer of this look. I’m only a cheap laborer who manufactures things based on the sample. That is what “Made in China” is all about: the West provides the concept; China supplies the material and labor for production. They are just like Chinese-made products consumed by the West.

CM: There was this work years ago that completely baffled me, called “Standpoint” (2003)—what was that all about?

2003

SY: That is an inflatable installation that responds to sensors in the environment. Before the viewer steps into the space, the lighting is normal and the inflatable daggers placed around the walls are de-inflated and droopy. When the viewer steps into the space, the light immediately goes out, and the daggers, giving off red light, are automatically filled up and become erect. Sounds of quickened breaths play synchronously through the speakers. Through this format, which is quick and interactive, I am attempting to represent the reality of art. What seems to be instantaneously effective is in fact more like a performance, an art performance that sells on “attitude” and “position”.

CM: Tell us about your recent works, like “Under the Rule” (2017). Automotive design seems to be important — and not for the first time in your work (e.g. “We Don’t Want To Stop” 2006) — but now it’s like finding some archeological elements or fossils of animals that predicated automotive design or developed out of it. The idea of sequences seems to be important in these works.

SY: This is only a coincidence. Cars don’t really hold much special meaning for me. In fact, any kind of everyday object could be used as materials for art. In “Under the Rule”, I used the forms and movements of the “combined vocabulary of violence + ornament” (dismantling, slicing, welding, reshaping, painting the surface … etc.) to break down the objects’ original appearance. I also attempted to reconstruct a syntax through the absolute control of height (based on the 1.36-meter height restriction a “one size fits all” approach where everything above 1.36 m tall would all be cut off): in it we have this form, this dimension of reality which hints at an aesthetics of power. Here, it is very important for the fragmented objects to serve as metaphors for the body and vessels for on-site control. Moreover, they are re-translations of a different kind of reality, as well as evidence of the body that had been irredeemably disappeared and abstracted.

But what is particularly interesting is that, under the absolute dictates of “one size fits all”, two things of varying nature continued to exist: one is the car axle that is too hard to be cut; the other is the engine oil left inside the car, one that is fundamentally impossible to cut. They are essentially “defects” that exist outside of the plan. Here, I see them as two suspended, yet separated words. Even though they still exist within the rule, they are nonetheless fluid, and occasionally knock into each other! They form a tenuous juxtaposition with objects that had already been cut, re-melded, and painted on-site. Evidently, they have the potentiality of breaking down the live syntax I constructed. In this sense, they are futuristic, carrying unknown powers … This was the one thing that excited me the most about this exhibition. That is such a “defect” would constitute the heart of my next conceptual inquiry.

About “Sorry there will be no documenta in 2007”

CM: Tell us about your documenta work. At the time, and even still, almost all artists consider it the height of recognition to be selected for documenta, and somehow it is even more important for Chinese artists. Your response was to stage a scene with a black hording around one of the main buildings with “Sorry there will be no documenta in 2007” printed on it in large white letters. Why did you do this?

SY: I have to clarify, I did not in fact participate in documenta 2007, but rather a paper-based art project about documenta. Though it had something to do with documenta’s organizing committee, it was not a part of the exhibition. So these images you are looking at are actually a virtual project executed on paper. Originally I wanted to make a fake public website in the name of documenta’s organizing committee, to announce to the world: “We are very sorry, for numerous insurmountable reasons, documenta 2007 will be cancelled.” However, the project was somehow not implemented. So we adopted a different plan, which is the virtual project on this piece of paper.

SY: I just remember that after 2006, the entire art world seemed like a manically spinning machine and anything to do with art on a global scale got sucked into it. Whether it was curators, artists, art organizations, foundations, galleries, collecting organizations, or the public, everyone seemed as though they were galloping wildly running around the world from one place to another, non-stop. It seemed that art didn’t have time to make people think any more, nor did it need to think for itself. Everything seemed like a luxurious yet thoroughly exhausting art party. In these kinds of circumstances, should art not stop for a second, and take a break? Should documenta, which we deem so important, lead by example and take a break? That is the fundamental motivation I was trying to convey through this work. I thought, we should let all the artists in the world rest; let the curators rest; let the critics rest; let the public rest; let the art organizations rest; let the foundations rest; let the sponsors rest; let the galleries rest, and let the media rest.

Pause

CM: Why did you stop making art?

SY: Just like the backstory behind “Sorry, There will be no Documenta in 2007”, as an artist, I was equally led by by my neck like a show pony to keep walking around the track. Exhausted in body and spirit, I lost the passion to create. So in that moment I very much wanted this crazy art machine to stop. Of course, this crazy art world would not stop operating because of my proposal. But as an individual, I decided to lay art production aside. I don’t believe that the making of art needs “perseverance” to be nourished and sustained. I think that art needs passion but not perseverance. That is not to say that passion is the only factor. But it is a basic prerequisite for art making. Without this prerequisite, art would be powerless. As a result, I decided to postpone or defer art making, laying it aside. Coincidentally, Lorenz asked me to take on a position to help the gallery with artistic direction. So I shifted my role without a hitch, transitioning from an artist to an art worker. But one thing is very important, regardless of how my roles changed, I had never left art.

CM: Why did you start making art again?

SY: The truth is, between 2006 and 2014, I still made work on and off. It was only continuing the projects I had before. Deferring my art making was really only a temporary suspension. With the temporary switch of roles within art, I hoped to re-assess art from the mentality and perspective of a non-artist, and re-accumulate the passion and energy for creating work. That is how my solo show “Let All Potential Be Internally Resolved Using a Beautiful Format” at MadeIn Gallery came about.

CM: Is there a connection with your older work or is your recent work totally new, a break with the past?

SY: Many think that my works now are very different from past ones. I think that this perception is fundamentally based on a superficial, visual assessment. In fact, my current work and past ones are internally connected. It’s just that as my concepts develop, the forms of presentation have changed. Whether my experimental stage in the early 90s, my “New Image” stage in the late 90s, Hallucinatory Realism after 2002, the erasure of concepts after 2006, or even my latest works, they are all about the body, and are firmly latched on to the present. If we were to compare the sound installation “Live broadcast: Reverberations and Echoes in a Private Space” that I made at home in 1995 to my newest work made in 2017, “Under the Rule”, we will find that they are both based on the way that the body is controlled by reality. It’s just that in “Under the Rule”, forceful intervention and the sense of pain are already covered up by the superficial “beautiful” skin. In that sense, it is more confusing.

Hunters & Collectors

CM: Why do you collect art? What makes a good collector?

SY: Art collecting is as exciting as when an archaeologist discovers a valuable piece or artefact through the process of constant excavating. They often bring my thoughts and memories into the past or the future. That is perhaps the reason why I like collecting art so much. I remember on November 28, 2013, I took part in a Wechat art auction organized by Doublefly members Lin Ke and Yang Junling while travelling on the high-speed train, and bought a series of watercolors painted on paper garbage bags. This auction association claiming to be the best in China was definitely the first auction to take place on Wechat. Only from then on did I start to consciously collect art. It sometimes even spun out of control. Of course, compared to many other collectors, I am at most an insignificant art collector. I can only collect a few interesting works within my limited budget. The only advantage I have is being an artist, so I can use my professional eye to judge and select what I see as good work. I don’t attempt to copy others’ taste, nor do I care about the work’s medium or market. I cannot define what it takes to be an excellent art collector. I can only share my own suggestions. Basically, my collection could be divided into three categories. The first is works by peers and friends: some are exchanges, birthday gifts, auctioned off on self-media Wechat platforms, or even experimental works discarded by friends that I salvaged. Of course, some are bought. The second is about remembering and commemorating art history (it has the fewest works). These include small conceptually-distinct works by masters who are extremely important to art history, ones who I venerate deeply. These types of masterpieces are rarely popular on the art market, and that makes it possible for me to save up money for collecting (some of which are co-purchased by me and a few good friends). The third category is mainly made up of works by young artists or art collectives. Some of them are quite active in art scenes abroad, while some exist on the periphery or outside of the art world. But I feel that they all hold immense possibilities for the future.

CM: Do you know any good collectors?!

SY: There are quite a lot of good collectors in China, many of whom I know. But it’s mainly limited to saying “hello” to each other at openings. Rarely do I personally know them.

CM: I get the feeling that the Western relationship with China’s art scene is quite strange. It doesn’t feel like a dialogue at all but more like a radio station always broadcasting the same tune and more to collectors and not to artists.

SY: That is because the power of capital can send both the Western and the Chinese art worlds into a state of rapture, for only capital can be quantified as the absolute marker for art — something about which volumes and volumes can be written! And yet before an artist or an artwork gets “coronated” as capital, they are nothing. Nobody will pay them any attention, let alone have a deep dialogue with them.