At China: Early Photography and Photographic Technique

Taikang Space (Red No.1-B2, Caochangdi, Cuigezhuang,Chaoyang District, Beijing), Mar 19–May 19, 2015

Old Photos from the Palace Museum’s Permanent Collection

The Gate of Divine Prowess at the Palace Museum, May 17—July 17, 2015

When discussing the ontology of photography, critics often invoke Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida. From its outset, the book is an inquiry into “the nature and essence of photography”, setting forth that photography possesses attributes which cannot be replaced by any other medium. In the opening paragraph, Barthes writes, “One day, quite some time ago, I happened on a photograph of Napoleon’s youngest brother, Jérôme, taken in 1852. And I realized then, with an amazement I have not been able to lessen since: ‘I am looking at eyes that looked at the Emperor.’” Though this “way of seeing” which came to Barthes in his eureka moment did not resonate with his friends and associates, it is a vivid illustration of the value and significance of photography (as an action) as well as the limitless possibilities present in interpreting photography (as a noun). Here, there is no need to elaborate on the complex relationship between art and reality, but I must emphasize what Barthes’ interpretive approach to photography confirms: as the artistic practice most seemingly proximal to reality, photography—even documentary photography—is not merely a product of subtraction from reality. By gazing upon a photograph and engaging in the spiritual acts of imagining, remembering, or revering the subjects, objects, or events in the photograph, we superimpose a new layer of meaning on to the photo. This is why old photographs in particular elicit so much interest. Photographs which have historical value seem to possess the supernatural power to pass through time and space; though they depict a far off age, they still resonate with their viewers.

Most early photography related to China comes from Western explorers, missionaries, and imperialists who were often an amalgamation of these identities, though there are a few masterpieces from photography studios run by Chinese photographers. Many of the translations published in recent years reflect the abundance, varied subject matter and diverse techniques prevailing in these photographs, as well as their value as a field of study. For example, Illustrations of China and Its People, published in London from 1873 to 1874, had the goal of “giving western readers a comprehensive introduction to China”. The Scottish photographer John Thomson carefully catalogued the last days of a timeworn dynasty reeling from the effects of the two Opium Wars by photographing rich anthropological subjects including paifang archways, beggars, and women’s hairstyles; the photographer included descriptive captions for each photograph to give a complete picture of “China” and “the Chinese”. If we return to contemporary times, Chinese-American photographer Liu Heung Shing’s China After Mao should be counted as one of the classic works documenting social upheaval during China’s Reform and Opening period. Apart from the understated but sophisticated photographs, the book is also enriched by Liu’s unique personal history as a photographer born in China but educated in America. This history spares him from simplistic and brutal demarcations of “East vs. West” or “Chinese vs. foreign”; his work is not easily placed in any ideological camp, and cannot be approached in conventional ways. Since the inception of photography, identity politics between the viewer and the viewed have been an inexhaustible topic for debate, whether the stakeholders are the photographer, the photographed, or the photograph’s audience.

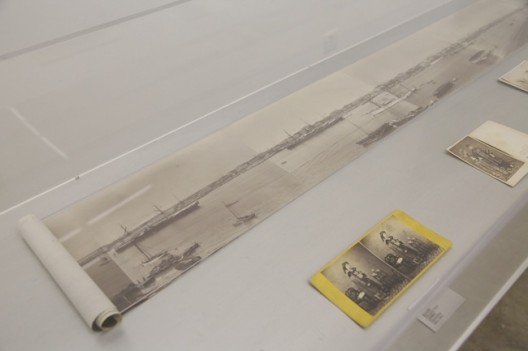

Only in such a special context can we hold a more informed discussion of recent exhibitions including “At China: Early Photography And Photographic Technique” (Taikang Space, Beijing) and “Old Photos from the Palace Museum’s Permanent Collection”. These two exhibitions are small but exquisite, both featuring outstanding frameworks of spatial presentation and content. The time span covered by both exhibitions includes the 19th Century, featuring some of the first photographs of China in existence. The content of the exhibitions differ; the “handpicked” or “selected” photographs on show at the Palace Museum tend to reflect the function of photography as a tool for official propaganda, documentary, and court pictures, while Ge Lei’s private collection shown at Taikang Space is more representative of the aspect of common people’s lives.

《在中国:早期照相与工艺》展览现场

The Occidental Gaze and Western Photographic Technique

From the 19th century onwards, China signed a series of unequal treatises including the Treaty of Nanking and the Treaty of Tientsin. The nation was forced to open ports in Guangzhou, Xiamen, Shanghai,Tianjin and other cities to western trade. During this time, an influx of western photographers and photographic techniques also flowed in through these ports and throughout China. Taikang Space sets out this important historical context with window displays and panels. The exhibition’s first section—“Photography at China: 1845—1895”—meticulously sorts through developments in photography brought in via the commercial ports during this period, clearly presenting the sprouting and spread of photography in China.

As the title of this exhibition explicitly states, the development and dissemination of photographic technique serves as one of the major guidelines for sorting through this period in the history of photography. From the albumen process to wet plate collodion, from gelatin dry plates to photographic paper, the evolution of technology lowered the costs and barriers of photography in terms of time, money, and energy, making photography accessible to a greater portion of the population.

早期摄影工艺

In the “Early Photographic Technique” portion of Taikang Space’s exhibition, the value of retaining these traditional techniques is reflected by the contemporary works of six Chinese photographers. Techniques like the daguerreotype, the cyanotype, and Van Dyke Brown became historically obsolete due to certain deficiencies, including the difficulties of preserving these art forms and their lack of portability. However, by supplementing them with modern technology, these techniques have received a new lease on life. They have become fresh sources of inspiration, used to document and record new issues in contemporary society and among individuals. Though the exhibited works are somewhat lacking in innovation and experimental elements, the use of traditional photographic techniques by contemporary photographers reminds us of the diversity and complexity of the medium as a language system. Nowadays, when we can easily acquire thousands of images at a low cost, this complexity is largely ignored, which accordingly situates us in a dilemma about our relationship with visual language: we simultaneously devalue the importance of photographs, while paradoxically growing more and more dependent on them. A retrospective on traditional photographic techniques should involve more than “technical control” or “enthusiasts” commemorating the “elegance” of “classical beauty”; it should be a means to continue exploring the rich possibilities of photography.

A formal analysis is most worthwhile for the section of the Taikang Space exhibition entitled “A View from West towards East”. Over forty illustrations and photographs of China in the 19th century reflect how the West viewed China, and the hidden assumptions therein. A photograph taken in the 1890s depicts an Englishman dressed to imitate Li Hongzhang, who was a politician, general and diplomat of the late Qing Empire. Another taken between 1850 and 1860 reflects Chinese court life in the eyes of westerners. In the photograph, a Western man is shown wearing full court regalia, with the mouthpiece of a hookah pipe dangling from the corner of his mouth. Seated on his left, a woman who could be his wife is also dressed in the Chinese style clothing of a Qing Dynasty noblewoman; the thick platform shoes on her feet are the “horse-hoof” shoes seen in the Manchu courts. The husband and wife are seated on a pair of wooden chairs on a platform, standing beside them are two women in waiting dressed in plain clothes. In the photo, the servants’ eyes are downcast; the wife is gazing somewhere off camera, and only the husband is staring straight into the camera lens, confronting the viewer’s gaze. The scene is deliberately laid out in an oriental style—a carved stone sculpture is placed on the table; in the background are Chinese paintings, and the chairs in the foreground are also decidedly Chinese. However, all of these set pieces, and their complex arrangement only serve to confirm the influence of the Western tradition of portraiture. You can find a highly similar setting seen in Hyacinthe Rigaud’s famed portrait of Louis XIV , and it strikes a vivid contrast with early Chinese portraiture which tended towards austere or even dull sets.

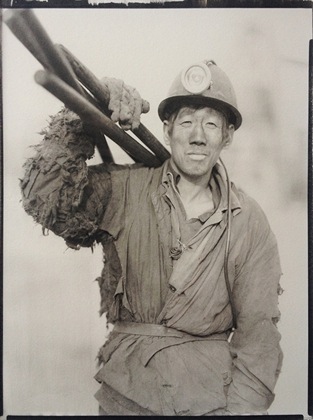

芦笛,《矿工》 ,铂金印相,2006年

孙诺,《时间的灰烬》,蛋白印相,2011年

W.G.托德照相馆,汉口,1860年代,名片格式蛋白照片

西方人想象中的中国宫廷生活,佚名摄影师,1850-1860年代,蛋白立体照片

Old Palaces, Old Friends, and Old Stories

The other new exhibition, “Old Photos from the Palace Museum’s Permanent Collection” is the first showcase of photographs from the Palace Museum’s permanent collection since the establishment of the People’s Republic. The Gate of Divine Prowess at the Palace Museum has been selected as the exhibition’s venue. The exhibition space (which seems slightly too small) holds nearly 300 items including old photographs, albums, and film negatives, yet the accompanying textual annotations are rich and detailed. There are reportedly nearly 20 000 old photographs and over 20 000 glass plate negatives in the Palace Museum’s collection. Most of the photographs date from the late Qing and Republican period and involve politics and diplomacy, military reform, culture and customs, amongst other subjects.

Upon stepping across the threshold of the Gate of Divine Prowess, visitors are met with a series of “time traveling” photographs—images of the Forbidden City juxtaposed with photos from the present day. Subjects from the old photographs remain in black and white, forming a sense of dissonance with the color photographs of the Forbidden City today. The figures appear like specters of the soul, simultaneously evincing their former existence while indicating their absolute absence from the scene in the present day. The contrast of black and white versus color testifies to advances in photographic technology. By knitting together history and the present, the photographs might allude to the Western origin of color photography, and its encounter with a sealed off empire “of the East” deeply rooted in tradition.

《光影百年——故宫老照片特展》展览现场

《光影百年——故宫老照片特展》展览现场

古今故宫合成照

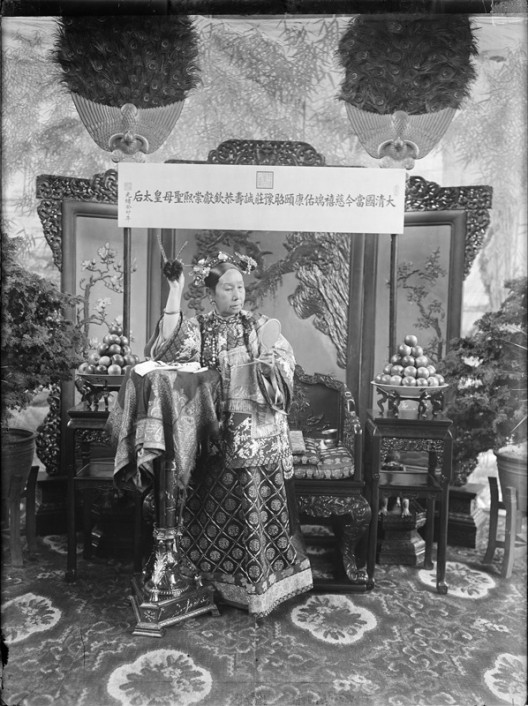

The four sections of “Old Photos from the Palace Museum’s Permanent Collection” are “The Palace at Twilight”, “Faces of the Empire”, “Industrial Reform”, and “Rebirth of the Forbidden City”. Each section is a retrospective on architecture, people, reform, and the rise and fall of the Palace Museum, respectively. The most topical of these photos is undoubtedly the series of photographs featuring Qing Dynasty royals and nobles, including Empress Dowager Cixi and the family members of the last Emperor Puyi. It is said that the Palace Museum collection contains over a hundred photographs of Empress Dowager Cixi alone. In these photos, she is wearing over thirty different outfits. Among these, group photos are the most common ones, such as “The Empress Dowager Cixi and Others before the Hall of Dispelling Clouds at the Summer Palace”. There are also more unique photographs including solo portraits of the Dowager Empress in the style of traditional paintings of courtly ladies such as “The Empress Dowager Cixi Gazing into a Mirror” or The “Empress Dowager Cixi in the Guise of Avalokitesvara” which was taken by Yu Xunling in 1903 on the eve of Cixi’s 70th birthday. Yu Xunling was the second son of diplomat Yu Keng who was minister to the French Third Republic. He was also the first photographer to shoot Cixi in the imperial palace. Many of the surviving photographs of Cixi were taken by Yu. For his father’s post as a foreign minister, Yu Xunling and his two sisters, Derling and Rongling had accompanied their father on his trips abroad to Japan and Europe. Upon returning home, Yu Xunling became the court photographer, while Cixi made his two sisters ladies-in-waiting. Cixi was a devout Buddhist throughout her life; her religious belief was the reason she was sometimes addressed as “Guanyin Bodhisattva”, commonly known as “Goddess of Mercy” in English. Cixi mimicked Guanyin in a series of pictures, thereby replacing her secular identity with her religious faith. In the 1903 photo, she is seated cross-legged in the center of the frame wearing a Pilu hat and Five Buddha Crown on her head and holding a string of prayer beads in her right hand. Standing to her left and right are head eunuchs Cui Yugui and Li Lianying. The two eunuchs are dressed as two protector deities with dust whisks held in their hands. These figures stand behind a foreground of lotus leaves, and in front of a bamboo background to form a standard image of the Guanyin Bodhisattva. Cixi had several similar photographs taken. In “Empress Dowager Cixi and Attendants on a Barge”, figures dressed as members of a fairy procession surround Cixi dressed as Guanyin. Cixi’s self-fashioning portraits recalls the aforementioned Western family’s misguided attempt to pose as Qing nobles; in comparison, Cixi’s series of photographs seem all the more charming and interesting.

The link between apparel and identity is all the more apparent in the photographs of Puyi’s generation. During the Tongzhi Restoration Period, a young Puyi is photographed wearing Qing gunfu, ceremonial dress worn by an emperor, but later, he is photographed as a Chinese gentlemen garbed in a Western suit (see “Puyi and the Tennis Aficionados”). His wife, Wanrong, was also photographed wearing the four different costumes—Qing court dress, casual dress, in a qipao, and later, a kimono. The exhibition presents these four photographs of Wanrong in a series outlining how an individual was displaced, undergoing changes in fortune and lifestyle from the decline of the Qing Dynasty to the puppet state of Manchukuo. Meanwhile, more everyday images of Puyi such as “Puyi Seated Sideways on a Walking Stick Going to an Outing and Puyi and Pujie” not only present Puyi as a commoner but also reflect how photography was becoming cheaper, more widespread, and increasingly innovative.

“Dowager Empress Cixi” is the photograph probably drawing the most attention from viewers at the show. Placed independently at the end of the exhibition hall, this portrait was also taken by Yu Xunling at the Summer Palace during Cixi’s 70th year. At the exhibition, visitors take out their phones and attempt to surmount the reflection from the photograph’s glass frame to take a perfect picture. Repeatedly, they press camera shutters to capture this portrait of Cixi; it is perhaps the moment when they can get closest to this legendary historical figure.

《慈禧太后对镜簪花像》,1903年

慈禧旧照

《溥仪与网球爱好者》,20世纪初

《坐在文明棍上的溥仪》,1920年代

《慈禧太后》由裕勋龄于1903年在颐和园为慈禧拍